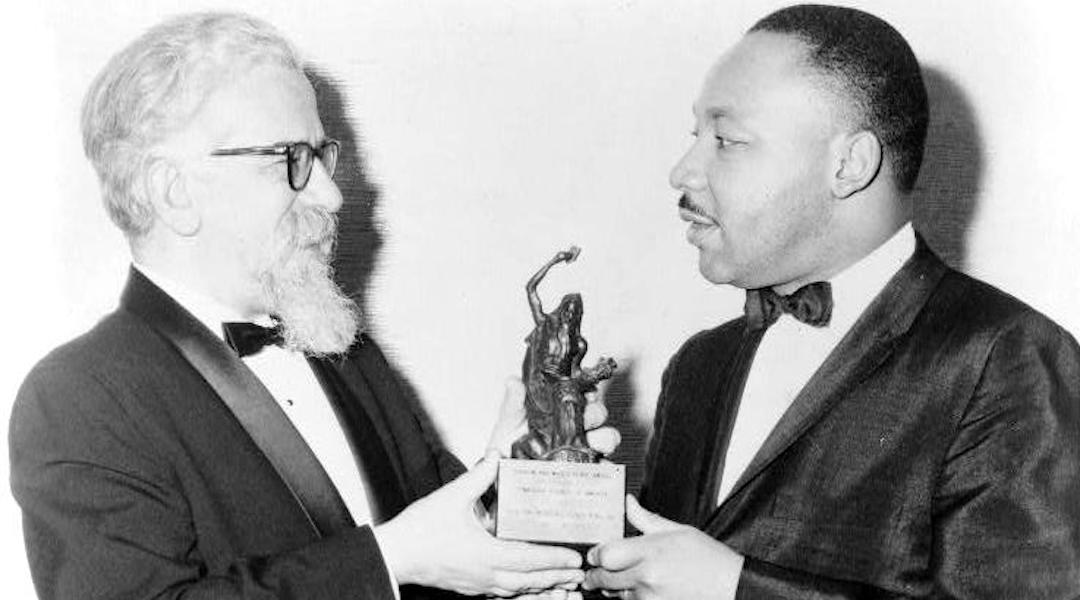

One was a black Baptist preacher, the other a white- bearded rabbi born to lead a Chasidic dynasty.

In life they stood arm in arm as men committed to righting their nation’s moral wrongs, as religious leaders unparalleled in influence and stature — and as personal friends.

Slavery and the struggle for redemption: The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel knew both intimately, and devoted their lives to helping their people reach a Promised Land.

For King, that was a land free of racial discrimination. For Heschel, it lay in inspiring people to develop an intimate relationship with God, to do God’s work in the world and to feel joy in it.

Now, decades after their deaths, King and Heschel are being paired once again.

This year, the 25th yahrzeit of Heschel’s death falls on Jan. 16, just days before King’s birthday is celebrated as a federal holiday on Jan. 19, 30 years after his assassination.

Hundreds of activities are slated around the world to remember Heschel. Some of those, particularly in the United States, will commemorate King as well.

It’s reflective of his widespread influence that about 300 communities of Jews around the world — from Vancouver, British Columbia to Bennington, Vt.; from Greensboro, N.C., to the Netherlands; and from Berlin to Jerusalem — are honoring Heschel’s memory and legacy in an organized way.

Heschel was — and is — the closest thing that many liberal Jews will ever have to a rebbe, a Chasidic master whose teachings and writings guide their lives.

For many, Heschel’s vision of man’s role in the world was so powerful that it resonates today even more strongly, perhaps, than it did in the first years after his death on Dec. 23, 1972.

“What was amazing about Heschel” was the sense he gave that by working to fix the world’s wrongs, “you really are repairing the universe, bringing to it a fusion of the Chasidic and prophetic,” said Rabbi Arthur Waskow.

Waskow, director of Philadelphia’s Shalom Center, which is devoted to bringing Jewish spirituality to bear on issues of social justice, has been centrally involved in making people aware of Heschel’s yahrzeit.

For more than six months he has been helping organize events all over the world by providing community leaders with excerpts of Heschel’s work and writings about the late rabbi, and sharing information about him over the Internet.

Heschel’s influence over nearly all segments of the Jewish community — as well as over Protestants and Catholics, whites and blacks — has been profound, say people from each of those quarters.

“Heschel and my father were prophetic voices in the wilderness, crying out and urging us to come together and go beyond our perceived differences and limitations,” Yolanda King, the civil rights leader’s eldest child, said in a telephone interview.

“Through their ministries and work, they really urged us to be the best that we can be, summoned us to be our best selves.”

Born in Warsaw in 1907, Heschel was nurtured in the bosom of a great Chasidic community and recognized as an “ilui,” a child prodigy in Torah.

Both of his parents were from prominent Chasidic families, his mother the twin sister of the Novominsker rebbe and his father the grandson of the Apter rebbe.

While a teen-ager, Heschel began reading secular books, in addition to studying Talmud, his daughter, Susannah Heschel, wrote in the introduction to the 1996 book of her father’s essays she edited, “Moral Grandeur and Spiritual Audacity.”

He went to Vilna, Lithuania, to study at a Gymnasium, then later to university and a liberal Jewish seminary in Berlin. He was one of the few students there able to develop relationships with people at the Orthodox seminary down the street, wrote Susannah Heschel, who has been appointed an associate professor of Jewish studies at Dartmouth College.

After being deported by the Nazis to Poland in 1938, Heschel escaped just six weeks before the German invasion of his homeland in 1939, thanks to an invitation to teach at the Reform movement’s Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati.

There he ate alone in his room, since the cafeteria was not kosher. He was grateful for the job but frustrated with his students’ limited knowledge of Jewish texts.

Heschel quickly discerned a profound problem among American Jews — one that many say remains a problem today.

“Heschel did not find enough American Jews struggling with the reality of God nor responding to divine imperatives,” the author of two books about him, Brandeis University professor Edward Kaplan, wrote in an article.

Heschel judged American Jews as being in the throes of a second Holocaust – what he called “spiritual absenteeism,” Kaplan wrote.

By the time the war was over, Heschel’s mother and two of his sisters had perished in Hitler’s fires.

In Ohio, Heschel met and married his wife, Sylvia, and within a few months was invited to teach at the Conservative movement’s Jewish Theological Seminary.

They moved to New York, where he remained at the seminary for close to three decades.

It was after he married that he began writing his most important works — “Man Is Not Alone” and “The Sabbath,” both published in 1951, “God in Search of Man,” in 1952, and “Man’s Quest for God,” in 1954.

In the 1960s, he was politically active, becoming a prominent advocate for the black struggle to attain civil and human rights and a powerful opponent of the Vietnam War.

“Until Heschel, Jewish liberalism was very much the province of Reform rabbis, and he felt their Judaism wasn’t very deep,” according to Rabbi Arthur Green, who studied closely with Heschel while at JTS.

Then there were Jews, Green said, who were very observant but “who cared nothing for the outside world. Heschel bridged that in a very authentic and unique way.”

Heschel met King at a conference on race and religion in Chicago in 1963 and they became fast friends.

He protested with King for the black cause in many venues. King, in turn, articulated strong support for Israel and against the anti-Semitism that emerged in the Black community a few years later.

In 1965 Heschel marched, arms linked with King’s, to Selma, Ala., protesting discrimination against blacks.

For Heschel it was the quintessential political expression of his religious mandate. “I felt that my feet were praying,” he said afterward in an oft-quoted statement.

When Heschel founded Clergy and Laity Concerned About Vietnam, he asked King to speak at Riverside Church for the cause, something that was politically risky for the minister at the time.

But even after many others abandoned King and his cause, Heschel stood by him, said Yolanda King.

In 1968, just 10 days before he was assassinated, King addressed a conference of Conservative rabbis at Heschel’s invitation.

The rabbi introduced his friend by saying that “Martin Luther King Jr. is a sign that God has not forsaken the United States of America,” recalled his daughter.

Heschel was the only Jew invited to speak at King’s funeral.

The two shared many theological parallels in their writings and speeches, said Susannah Heschel, most centrally “that God is not the `Unmoved Mover.'”

Heschel’s political activity “was barely tolerated” at JTS, according to Green.

But some of his students, including Green, frustrated as their teacher by the passivity of American Jews, decided to change things.

In the late 1960s they founded Havurat Shalom in Somerville, Mass. That community became the model for small, participatory havurot — groups of Jews who gather to study and pray together — and the basis of the Jewish renewal movement.

“Many of us who heard his impassioned anti-Vietnam speeches and involvement in the struggle for integration” felt that this “radical vision had to have a [Jewish] address,” Green said.

Heschel remained active until soon before his death, which came as he slept on a Sabbath evening a quarter-century ago.

Despite his unmatched level of commitment to social action, it was not the heart of his life, said his daughter.

For her father, “The starting point wasn’t marching to Selma, it wasn’t social activism, it was being a mensch,” she said.

More than anything else, she added, he was concerned about “treating other people with consideration and compassion.”

“He said that every Jew is an image of God, and when you look at somebody you should be reminded of God and to live your life so people can be reminded of God,” Susannah Heschel said. “And he did that.”

The Archive of the Jewish Telegraphic Agency includes articles published from 1923 to 2008. Archive stories reflect the journalistic standards and practices of the time they were published.