PHILADELPHIA (JTA) – One thing is constant about life on an aircraft carrier: the noise.

The roar of jet aircraft engines on the deck is complemented by other sounds heard throughout the ship and below deck: the explosive booms coming from the catapults launching planes and the reverberations of the restraining wires on the steel deck that enables others to land.

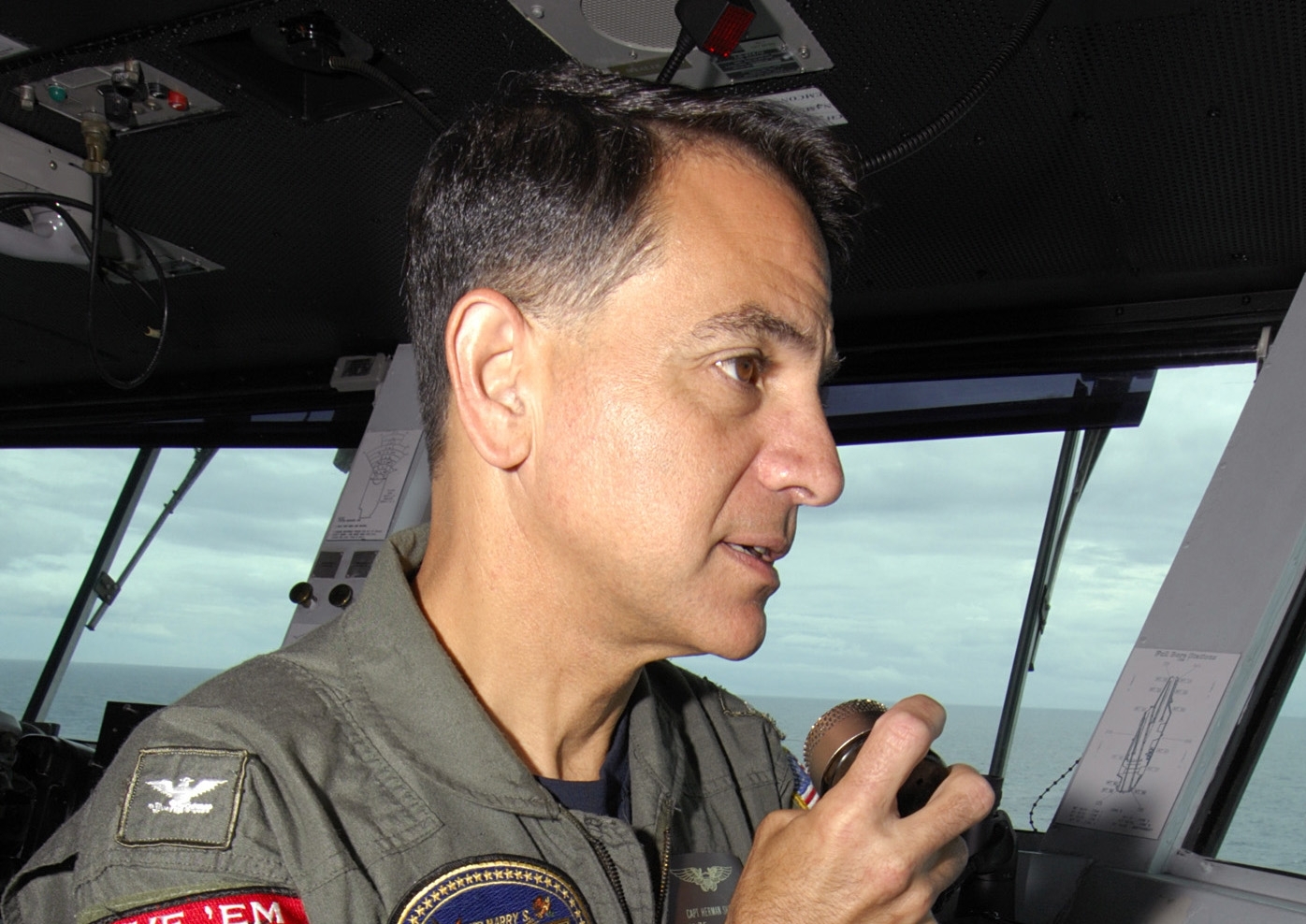

Yet the sound that seems to garner the most attention on board the USS Harry S. Truman is, ironically, among the softest they will hear: the even tones of Capt. Herman “Herm” Shelanski.

“I’ve never heard him even raise his voice,” says one of Shelanski’s officers, who admits that this low-key style is hardly typical of naval behavior when it comes to the person in charge. “But he’s always in command of the situation. He’s the sort of a person who makes you want to meet or exceed his expectations.”

Another officer, referring to the captain’s average height of approximately 5 feet, 7 inches, says Shelanski’s “physical stature isn’t so big, but his presence is huge. Everyone on board feels it.”

Shelanski, a native of Wynnewood, Pa., is a 27-year Navy veteran who has risen from a young aviator piloting E-2 Hawkeyes to being the commanding officer of one of the Navy’s elite weapon systems.

The Truman is a Nimitz-class nuclear aircraft carrier whose air wing of more than 80 tactical and support aircraft – including squadrons of the latest F-18 Hornets and Super-Hornet jets – can project America’s strength around the world.

Shelanski, who is married and the father of two teenagers, took command of the Truman in the spring. Put to sea In the Atlantic Ocean in September, some 200 miles from its home port of Norfolk, Va., the Truman will sail to the Persian Gulf, where its aircraft and pilots will be flying missions providing support for U.S. troops fighting in Iraq.

Shelanski’s role is to be, as he put it, “mayor of the city” – of a floating airport that’s home to more than 5,000 sailors and aviators. The Truman, as long as the Empire State Building is tall, is a vessel whose maze-like compartments below decks can take sailors weeks to find their way around.

While its namesake’s trademark “Give ’Em Hell” slogan is emblazoned around the ship as a symbol of its crew’s fighting spirit, another of the 33rd president’s favorite sayings is embodied in the conduct of the man who commands it: “The Buck Stops Here.”

“There’s a lot of different leadership styles and a lot of pressure to be who you are not,” Shelanski says. “But I’m a believer in being who you are and treating people with respect.”

Grandson of immigrants

Though decades of flying and sea duty have given him the experience of command, he makes no secret of the fact that a big part of who he is can be traced back to his origins. Shelanski is the grandson of Lithuanian Jewish immigrants to the United States who settled in Philadelphia in the early 20th century.

Asked what would prompt the son of a prominent doctor, who was a bar mitzvah at Har Zion Temple and a graduate of Lower Merion High School in the 1970s to join the Navy, Shelanski answers simply: “I always wanted to serve my country. And a lot of that has do to with being Jewish.”

Military service was hardly the norm for young middle-class Jews in the 1970s, but Shelanski says the message of pride and patriotism in America was a big part of his upbringing.

On his desk in his spacious and luxurious in-board cabin – used mostly for dinners and ceremonies – are pictures of his father, Morris, who served as a doctor in the Navy during World War II, and a cousin who was a naval aviator. Their example of service was and remains important to the captain.

“I knew that I was fortunate. A lot of our family died in the Holocaust. It makes me think of what could have happened if we hadn’t come to America,” he says. “I wanted to give back to this country. I also understood that the strength of the United States is directly proportional to the safety of Israel.”

Yet a career in the Navy was not really in his plans when he left the area to attend the University of Colorado, from where he graduated in 1979.

A self-described “outdoor kid” with an itch to fly, the following year found him at a naval aviation officers candidate school, from which he emerged with the newly minted rank of ensign. Two years later he earned his wings and was flying E-2C Hawkeyes.

‘But it was only going to be a temporary job,” Shelanski says. “I was going to do it for a while, and then go and be a doctor,” following in his father’s footsteps.

What changed his plans?

“I was having too much fun to stop,” he says. “I really enjoyed what I did. The intensity, the excitement and the thrill of it was what kept me in.”

And the fact that he was very good at his job. His record shows that from the start of his career, Shelanski was selected by his superiors for special responsibilities.

Flying the Hawkeye – the Navy’s tactical airborne warning-and-control-system platform – made him “the quarterback” of air missions.

During his first sea deployment, Shelanski says he found himself on the spot during a confrontation with Soviet aircraft that were attempting to track his carrier during a Cold War exercise in the Pacific.

A junior lieutenant at the time, he decided to change his air wing’s plans in the air to meet the potential threat. Shelanski radioed the change of plans to the commanding admiral on his ship and waited for the answer to his nervy request with baited breath.

After a pause, the response came back: “Roger that” – terse approval that was all he needed.

“It was a big thrill,” Shelanski says.

From there it was a steady progression of promotions as he rose to command a Hawkeye squadron; stints as executive officer of an aircraft carrier, the USS Ronald Reagan; commander of a fighting command ship, the USS La Salle; and various naval staff positions in the United States and at NATO.

Along the way he picked up a master’s degree in electrical engineering and space engineering from the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, Calif., and studied at the Armed Forces Staff College, as well as receiving nuclear-power training.

Shelanski’s duties have taken him to various parts of the globe, including postings in Italy and Bahrain, a place that was no less foreign to him than some parts of the United States and which differed greatly from his Northeast upbringing.

Physically fit at the age of 50, though he doesn’t fly very much anymore, he still works out daily in the ship’s gym and planned to compete with crew members in physical fitness tests.

Keeping the faith

One theme has been constant throughout a career: His willingness to be candid about his Jewish identity in a service where he often found himself one of the few, if not only, Jews.

Though he knows that anti-Semitism was commonplace in the military in his father’s day, Shelanski says he has discovered little prejudice, though much ignorance, about Judaism and Jews.

“It’s a little bit more responsibility,” he says of being the first Jew a sailor may meet.

“I always understood and loved Judaism. To me, being Jewish means asking how do you treat the stranger because we were strangers.”

His philosophy has been to “be open and honest, to care for people and to take care of people. The secret of success as a leader is to understand people. I got that from my parents, especially my dad.”

Despite the difficulties of being cut off from the usual Jewish connections, he found ways of holding on to his faith while staying close to his comrades.

In one instance, Shelanski recalls, while with a squadron in a remote location where everyone was away from their families on the holidays, he served as a kipa-wearing Santa Claus to cheer up his friends at a Christmas party. Under all circumstances, he says, “I wanted to say who I was.”

And when the only food available at stops at Navy bases was pork, he says, non-Jewish friends usually found him a piece of chicken or something else he could eat, showing the closeness and mutual respect that is part of naval life.

While keeping Judaism was tough as a junior officer, it’s much easier for a naval captain.

Aboard the Truman, Shelanski not only has his own private stores of food but has hosted kosher seders in his quarters for the crew. He also regularly attends Friday-night Shabbat services in the ship’s chapel along with the approximately 12 to 15 other Jewish crew members, a group that includes a cross-section of the crew: officers, aviators and enlisted personnel who say the Sabbath service provides an oasis of rest amid the stress of their 24/7 workdays at sea.

The centerpiece of Jewish life on the Truman is a Torah kept in an ark donated by the chapel of the Naval Academy. The scroll, which was dedicated at a formal ceremony in June, originated in Lithuania, where it was saved from the Holocaust.

At the ceremony was a Torah that Israel’s first president, Chaim Weizmann, presented as a gift to President Truman and which was on temporary loan from the Harry S. Truman Library in Independence, Mo.

For Shelanski, an affiliated Conservative Jew, the Torah dedication was “very emotional,” as well as something that brought Norfolk Jews and the Navy closer together.

As was the case on the Reagan, where he also helped bring a Torah to the chapel, most sailors didn’t know what it was.

“I wasn’t sure what the sailors would think,” Shelanski says. “But the response was tremendous. There wasn’t a dry eye in the place as non-Jews felt the importance of it. I’ve found that people liked to learn about Judaism. And Christians see it as a way to go back to their roots.”

Indeed, faith can be important in a profession in which lethal danger is commonplace.

That was brought home to the Truman crew even before its deployment in Iraq when one of its Hawkeye radar planes crashed into the ocean after a takeoff at night during an August training session for a young pilot.

Shelanski, who was asleep in his other, much smaller cabin just off the bridge, where he spends most of his time, says within seconds he was at the helm directing the search-and-rescue efforts.

The search lasted 36 hours, but Shelanski says it became apparent quickly that the plane and the three people on board would not survive. What they found, he says, was “heartbreaking” – wreckage and helmets, but no bodies.

It was the first crash of a Navy Hawkeye in 14 years, proving to Shelanski that the worst thing that can happen on board is “complacency.” It’s something he continues to fight.

“Carrier duty is very unforgiving of mistakes,” he says. “We have to learn from our mistakes.”

In the Gulf, the Truman’s planes are scheduled to fly as support for soldiers and Marines. Some of the crew are also slated to be on the ground, serving as liaisons between the troops there and the ship to coordinate missions.

Everyone and everything must be checked constantly and re-qualified, he explains.

“We know the pilots are going to be flying into harm’s way,” he says. “There’s always a risk. The better we train, the better our chance of success.”

Though the U.S. presence in Iraq has lost the support of many Americans, the Truman is prepared to do its part in the fighting.

“Some people in the Navy were upset about the decision to go in,” Shelanski acknowledges, “but that doesn’t mean we’re not enthusiastic to win. We go where our nations’ leadership tells us to go. Our task is clear and there’s not a person on the ship who doesn’t want us to succeed.”

History lessons

As a student of history, Shelanski says he is cognizant of the threat from Iran and its President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, who has declared his intention to destroy Israel and is attempting to gain nuclear capability.

“Most sailors and officers here are aware of the history,” he says. “We know what happened when another nation [Nazi Germany] that made threats of annihilation was ignored. The sailors are happy that we’re standing up to these people, and hopefully our presence will deter them.”

As with Iraq, he defers to civilian leaders to make the decisions about what to do. Still, Shelanski says he hopes diplomacy and a coalition of Western powers will cause Iran to step back from the brink.

But, he warns, the Iranians “should understand that we have more than enough to stop them.”

The crew of the Truman hopes to return home to Norfolk sometime next summer. For its captain, the first order of business upon that return will be to attend the bat mitzvah of his daughter, which has been postponed from earlier in 2008 to a date when he may be available.

That’s all part of the job for a naval officer who has taken his family all over the world many times and dreads the long separations that sea duty demands.

As to his own future after his term as captain of the Truman ends – he is scheduled to leave in early 2009 – Shelanski is uncertain. Some in the Navy consider him a serious candidate for promotion to admiral.

Though flattered by the idea, he says it’s a decision for his family. Shelanski isn’t certain he wants to uproot them again, which would be a certainty if he is promoted.

“We’ll figure that out when we get there,” he says.

But before the homecoming to which Shelanski is already looking forward, duty in a war theater awaits.

With that in mind, would he want his own children to follow in his footsteps?

His answer is in the affirmative.

“I’d like my children to serve,” at least for one hitch, he says, so they can give back to the country as he has.

“But that makes you think about what’s important enough to send my [children] out to get killed,” Shelanski says. “Unfortunately there are times when we must do that.”

Noting that all aboard the Truman are volunteers, he recognizes that “they’re all someone’s children.”

Most on board tend to speak of themselves as “warriors,” but their captain is aware of the cost of combat.

“I understand as a father what it means to see the consequences of war,” Shelanski says. “I know my sailors. They’re not numbers. They’re people. My goal is to bring everyone here home.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.