View of the renewed Israel Museum, including the Billy Rose Art Garden, Carter Promenade and Gallery Entrance Pavilion. (Tim Hursley, courtesy of the Israel Museum, Jerusalem)

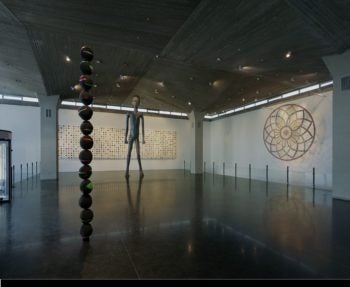

The renewed Upper Entrance Hall at the Israel Museum, featuring highlights from the contemporary art collection. (Tim Hursley, courtesy of the Israel Museum, Jerusalem)

Renewed galleries in the Jack, Joseph, and Morton Mandel Wing for Jewish Art and Life at The Israel Museum, Jerusalem. (Tim Hursley, courtesy of the Israel Museum, Jerusalem)

JERUSALEM (JTA) – A tawny sandstone sculpture of Nimrod, an ancient Hebrew warrior and hunter figure with a razor-straight back and proud stare, sits at the intersection between modern Israeli art and native art from Africa and the South Pacific at the recently renovated Israel Museum.

The 1939 sculpture by Israeli artist Yitzhak Danzinger is an example of the kind of cultural and aesthetic contextual links that James Snyder, the Israel Museum director, hopes to evoke in the reopening of the museum following a $100 million facelift he calls a “renewal.”

“It’s like a double helix,” said Snyder, who came to the Israel Museum in 1997 after 22 years at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, whirling his hand in the air to mimic a double helix’s shape. “The culture of the region and the culture of the world — they wrap around each other.”

The museum now stretches out on its sprawling 20-acre hilltop campus in Jerusalem across from the Knesset as a sleek and, indeed, renewed version of its former self.

Streamlined and expanded with 204,500 square feet for its refreshed collection galleries, archeology, the fine arts, and Jewish art and life are now easily accessible in one large exhibit hall designed with the guiding theme in mind of how objects and art can resonate across time and cultures.

The archeology wing, which traces the development of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, boasts a “House of David” — an inscription from the ninth century BCE seen as part of a monumental stone. It’s considered the earliest source backing archeological evidence that there was a dynasty sprung from King David in the Land of Israel. On display for the first time anywhere is a rare Crusader-era fresco that was on the wall of a 12th century Jerusalem abbey.

Fewer holdings are now on display amid almost twice the space. And there is no more trekking up a long pathway exposed to a broiling Jerusalem sun by summer or the cold winds and rains of winter. Visitors to the country’s largest cultural institution now reach the museum through an enclosed underground passage featuring a translucent glass wall on one side.

At the highest point on the museum’s outdoor grounds is a gleaming 16-foot-tall stainless steel sculpture in the shape of an hourglass specially commissioned for the museum’s reopening. Titled “Turning the World Upside Down, Jerusalem,” the work by the renowned Indian-born artist Anish Kapoor reflects, upside down, the city’s skies and landscape.

“Jerusalem is all about a very special relationship between the ground and the sky. This work attempts to bring the two together,” Kapoor said, describing the sculpture to the Calcutta Telegraph.

Asked how he completed the massive undertaking of overhauling the museum both on schedule (three years) and on budget in a country where such feats rarely happen, Synder answered, “Singlemindedness.”

It was Teddy Kollek, also known for having a driving vision, who came up with the vision of the Israel Museum back in the 1950s. It was a time when most people in the fledgling state were focused on survival, not cultivating a world-class collection of art and archeology.

Under Kollek’s guidance, the museum was opened in 1965, the same year he became mayor of Jerusalem, with modernist architecture designed by Alfred Mansfeld and Dora Gad. Under Snyder’s direction, the original architectural sensibility was preserved as much as possible by the architects leading the projects, James Carpenter Design Associates of New York and Efrat-Kowalksy Architects of Tel Aviv.

“The point of our project is not about new architecture and re-engineering in the building,” Synder said in an interview with JTA in his sunny office. “The point wanted to be about changing the way you present content.”

“The museum’s view had been a little bit that we are many museums under one roof, and I kept saying what’s amazing about this place is to find this breadth in one museum,” said Synder, an immaculate dresser who stands out in scrappy Israel with his rounded orange glasses, tie and blazer.

Over the years the museum, which has active and generous friends associations abroad, has acquired a 500,000-piece collection. Along with its Judaica and fine arts holdings, the museum long has been known for its outstanding regional archeology holdings. A major showcase has always been the Dead Sea Scrolls, which are housed in their own building.

More than $80 million of the renewal project was raised privately in Israel and around the world through individuals, families and foundations. Another $17.5 million came from the Israeli government.

Defending critics of the museum’s “universalist” approach, Synder says, “How can you avoid it? Look where we are — in Jerusalem, at the crossroads of the ancient world, where Europe meets Asia meets Africa and where monotheism happened. So if not here, where?”

The Jewish art and life gallery is designed to provide a view of Jewish life from the Middle Ages to the modern day showing both its secular and sacred dimensions. A highlight is a new synagogue route, which has the interiors of four synagogues, including ones from Germany, Italy and India. The most spectacular of all is a newly restored 18th synagogue from Suriname, a tiny South American country north of Brazil whose Jewish community, of Spanish and Portuguese origin, took root there a century before.

In the 1990s, with the Suriname Jewish community rapidly disappearing and the synagogue no longer functioning, the Israel Museum acquired the synagogue and brought its interior — white walls, large windows and sand-coated floor — and contents to Jerusalem.

Upstairs on the upper entrance hall of the fine arts wing, a much different image looms. It’s a towering sculpture of an African refugee boy in Israel made from Styrofoam and painted black. Israeli artist Ohad Meromi’s 2001 “The Boy from South Tel Aviv” stands in front of a painting of different colored polka dots by renowned English artist Damien Hirst.

Snyder thinks the sculpture of this underclass boy with a sense of majesty about him, as he describes it, has found its perfect home surrounded by the Hirst piece and others nearby that draw from African and European themes.

“It’s all about cultural synthesis in contemporary culture,” he said, his face breaking into a smile.

Then, adding what might be true for the renewed Israel Museum as a whole, Snyder says, “I hope we can keep it up.”