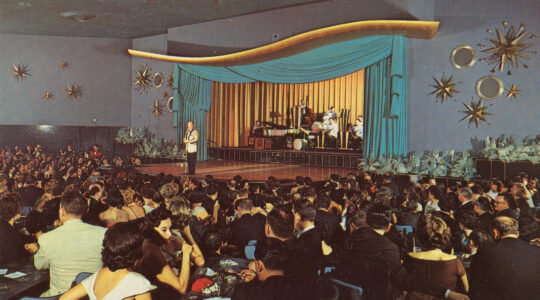

Anne Frank is portrayed as a marionette, remembered for what she represents rather than who she really was, in the new play “Compulsion.” (Joan Marcus)

BERKELEY, Calif. (JTA) — Mandy Patinkin says he only plays Jewish characters.

Che Guevara, his Tony Award-winning role in the 1980 Broadway play, “Evita”? Jewish. Inigo “prepare to die” Montoya in “The Princess Bride”? Also Jewish.

“Everything I do is Jewish. It’s who I am. It’s my soul,” said Patinkin, 57, whose 30-year career on stage and screen ranges from Barbra Streisand’s love interest in “Yentl” to “Mamaloshen,” his traveling celebration of Yiddish music.

Patinkin spoke to JTA from the rehearsal space at the Berkeley Repertory Theater, where he is preparing for the Sept. 16 opening of “Compulsion,” a new play about the world’s enduring fascination with Anne Frank.

“Compulsion” is playwright Rinne Groff’s fictionalized tale of the true story of Meyer Levin, an ambitious writer obsessed for 30 years with producing his own theatrical version of Anne’s diary, a right he claims was stolen from him by the people behind the 1955 Broadway play “The Diary of Anne Frank.” The new play is a co-production of the Yale Repertory Theatre, where it premiered in January; Berkeley Rep, where it runs through Oct. 31; and the Public Theater in New York, where it opens next February.

The intensity Patinkin brings to his work stands him in good stead to play Sid Silver, the Levin character in “Compulsion.” Silver, like Levin, is seared by images from the concentration camps and absorbed with bringing what he believed was Anne’s true message to the world versus what he called the “de-Judaized” version of the Broadway play and later Hollywood film.

“Anne was not a universalist, she was a Jewish idealist,” Patinkin said. “That was the core of [Levin’s] argument.”

It was playwrights Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett and producer Kermit Bloomgarden who universalized Anne’s story for American audiences in the 1950s. That was their goal, Groff says, perhaps understandably. Anne’s diary was, after all, the first widely published account of the horrors of the Holocaust, before the searing works by Elie Wiesel and Primo Levi.

Groff’s play “didn’t just speak to me, it shouted at me,” said Patinkin, who read the script last year and immediately told director Oskar Eustis it would be “illegal” for the play to be put on without him. “I was stunned at how it hit a nerve in my soul, on so many levels.”

Patinkin says his Jewish identity was “shaken to the core” by a recent trip to Auschwitz-Birkenau and Theresienstadt concentration camps.

“It was the sound of the train tracks that finally undid me,” he said. “I was headed back to Warsaw to continue to other places, and I had to stop; I couldn’t go any further. I couldn’t separate out how I was going to get off, go to a pretty hotel and have a nice meal, but if I closed my eyes, those sounds would have been taking me to a gas chamber.”

Saying he “can’t understand” how people can sit by and let something like the Holocaust happen, Patinkin added, “You can say I’m naive, that I don’t get it, but neither did Anne. She believed, as she says repeatedly and as we repeat in this play, that people are really good at heart.”

But “Compulsion” isn’t about Anne. It’s about one man’s obsession with Anne and, by extension, Groff says, the notion of many that only they truly understand the young diarist.

That was Levin’s mishegas, too. He read Anne’s diary in the late 1940s and extracted a verbal agreement from her father, Otto, to the stage rights. But Levin’s version was deemed unsuitable, other writers were brought in and Levin sued the bunch of them, including Otto Frank. He won, they appealed and the case was settled by a panel of “Jewish experts” who awarded Levin $15,000 in damages while ordering him to give up his quest.

Levin never did, and that’s the heart of “Compulsion.”

“It’s about his obsession with an idealistic vision of humanity that this child represented, and his core belief that it must be respected, protected and guarded in perpetuity, and rekindled every day,” Patinkin said. “This play asks us to what degree are we willing to go for what we believe in? Is the cost worth it? Are we living in a world of endless compromise?”

Patinkin has a long involvement with Jewish and Israeli causes. He received the 2000 Peace Award from Americans for Peace Now, is a board member of the Jewish sustainability nonprofit Hazon and supports the Arava Institute for Environmental Studies.

He said his activism stems from the lessons he learned growing up at Rodfei Zedek on Chicago’s South Side, as well as at the family dinner table. “Forgiveness, compassion — rachmones — and tikkun olam,” Patinkin said. “It’s pretty simple. Repair the world — my world, your world, our children’s world, the Middle East world, the world of the environment, health care, ethics, all those worlds.”

Years ago, New York theater impresario Joseph Papp told him to be careful what opinions he expressed about Israel in Jewish circles.

“He said, you’re going to make a good deal of your living from your community, and if you offend them, they may take a long time, if ever, to forgive you. So understand the risk,” Patinkin recalls. But, Patinkin says, the “desperate need” for peace in the Middle East leaves no room for niceties.

“We need to show we as a Jewish community are doing everything we can to heal [Palestinian] hurt,” he said emphatically. “And if they don’t have the means to heal ours right now, like the Torah says, the greatest gift you can give is the eulogy at another man’s funeral because he can’t give it back. The reasons are unimportant — stop it now.”