ROME (JTA) — When hundreds of thousands of people converge on the Vatican for the beatification of Pope John Paul II on May 1, a Brooklyn-born Jewish orchestra conductor will have an honored place among them.

Gilbert Levine, whose grandparents emigrated from Poland and whose mother-in-law was a survivor of Auschwitz, is a distinguished conductor who has performed with leading orchestras in North America, Europe and Israel.

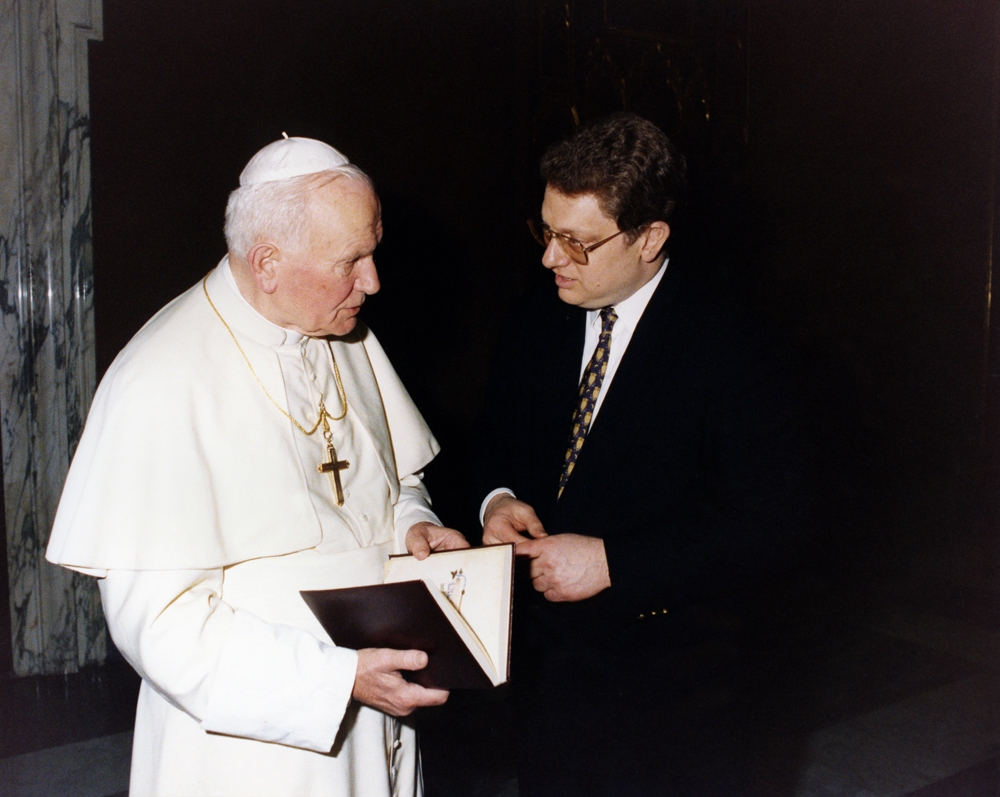

For 17 years Levine enjoyed a unique, and unlikely,- relationship with the Polish-born John Paul, one that led him in 1994 to become the first American Jew to be granted a papal knighthood. Levine says it also played a role in his deciding to become more involved in his own Judaism; he now attends an Orthodox synagogue.

The connection between the pontiff and the maestro had much to do with the fostering of Jewish-Catholic relations that was a cornerstone of John Paul’s papacy. But it had little to do with formal meetings or dialogue sessions.

Instead, from 1988 until John Paul’s death in 2005 at the age of 84, Levine worked closely with the Polish pope to produce a series of landmark classical music concerts at the Vatican and elsewhere. Their aim was to use music as a tool to foster religious dialogue and reconciliation.

“The pope ennobled and enabled me to think that this was a mission that I should take with me for the rest of my life,” Levine told JTA in a telephone interview from his home in New York. “And I do, very gladly.”

The performances included the unprecedented Papal Concert to Commemorate the Shoah held at the Vatican on Yom HaShoah in 1994.

At the beginning of the concert, which featured the recitation of Kaddish by the actor Richard Dreyfuss, six Holocaust survivors lit six candles — one representing each of the 6 million Jewish victims. One of the survivors was Levine’s mother-in-law, Margit, who was born in Czechoslovakia and had lost 40 members of her family in the Holocaust.

The pope “believed that wordless prayer was incredibly important, and I believed that music gave voice to that wordless prayer,” Levine said. “I think he understood and came to understand through me that art can do a tremendous amount.”

Levine recounted the story of his years working with John Paul in an intensely personal memoir titled “The Pope’s Maestro,” which was published last fall. The book traces a relationship that Cardinal Stanislaw Dziwisz, John Paul’s longtime secretary, termed “a deep, spiritual friendship.”

“If a Jewish kid from Brooklyn can have a spiritual friendship with the pope, then the world can learn something,” Levine said in a video presentation about the book.

The friendship began in 1988, in the waning days of communism, when John Paul summoned Levine to a private audience at the Vatican shortly after Levine had become director of the philharmonic orchestra in John Paul’s beloved Krakow, the city that had been his archdiocese before he became pope in 1978.

From the early days of his pontificate, John Paul had signaled that outreach to the Jewish world would be one of his priorities.

Born Karol Wojtyla in the small town of Wadowice in 1920, John Paul had had Jewish friends and neighbors, and he was an eyewitness to both the Holocaust and totalitarian communism.

Rabbi A. James Rudin, the American Jewish Committee’s senior interreligious adviser, recalls that at an audience at the Vatican with an AJC group in 1990, the pontiff “became very mystical and began to sway a bit and began talking about Friday afternoons in his hometown during the 1930s. He spoke of ‘candles in the windows, psalms being chanted.’

“He was clearly recalling erev Shabbat in Wadowice and his vivid remembrance of Jewish life in Poland before World War II,” said Rudin, author of the new book “Christians & Jews, Faith to Faith: Tragic History, Promising Present, Fragile Future.”

As pope, John Paul prayed at Auschwitz on his first trip back to Poland in 1979, and he repeatedly condemned anti-Semitism, commemorated the Holocaust, and met with Jewish leaders and laymen.

In 1986 he crossed the Tiber River to Rome’s Great Temple to become the first pope to enter a synagogue. There he embraced Rome’s chief rabbi and paid respects to Jews as Christianity’s “elder brothers in faith.”

A few years later John Paul oversaw the establishment of diplomatic relations with Israel, and in 2000 he visited the Jewish state.

John Paul’s death triggered an unprecedented outpouring of tribute from Jews around the world, and Jewish leaders joined the millions who crammed Rome for his funeral. There, in St. Peter’s Square, many faithful raised the cry “Santo Subito!” — a demand that John Paul II be made a saint right away.

The process ordinarily can take decades, even centuries. But John Paul’s successor, Pope Benedict XVI, put the Polish pontiff on a fast track toward sainthood, waiving the usual five-year waiting period after a candidate’s death before the process may begin.

Beatification is a venerated status just one step away from sainthood. It can be granted after a candidate for sainthood is judged to have interceded to cause a miracle.

In John Paul’s case, the Vatican declared that a French nun said to have had Parkinson’s disease recovered after praying to him. A second miracle must be recognized before John Paul can be canonized, or made a saint.

“Miracles after the death are the ones that count toward beatification and canonization,” Levine explained.

He said John Paul as pope had wrought a sort of personal miracle in his own family — by “bringing peace” to Levine’s mother-in-law, who had been deeply scarred by her experiences during the Shoah and the annihilation of her family.

“The pope reached out to her, wanted to see her,” Levine said. The pope spoke intensely with her during a private audience, Levine said, “and he showed her that he understood, and that he heard her. The voice that was inside her, he heard it.”

After this, he said, “She was a changed woman. It wasn’t that it made everything all right — of course it couldn’t. But finally someone had heard and it was just so powerful. She felt this reaching out to her, and she died at peace.”

Levine said his bond with the pope also had a profound effect on his own Jewish identity. He and his family now worship at an Orthodox synagogue in New York.

“My sense of Judaism became much more powerful,” he said. “The pope honored my Judaism and the faith of our family so deeply and so honestly, from his heart, that it really just opened us up to our Jewish faith and heritage even more than it was before.”

(Ruth Ellen Gruber’s books include “National Geographic Jewish Heritage Travel: A Guide to Eastern Europe,” and “Virtually Jewish: Reinventing Jewish Culture in Europe.” She blogs on Jewish heritage issues at jewish-heritage-travel.blogspot.com.)

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.