The “Seeking Kin” column aims to help reunite long-lost friends and relatives.

BALTIMORE (JTA) — Robert Krempel and Chanoch Kelman were friends in late-1930s Vienna. They had met through the Zionist Orthodox youth movement Brit Hanoar (Youth Covenant), belonging to a chapter that gathered on Shabbat afternoons and Sunday mornings for discussions and sing-alongs on prestate Israel.

The two boys also played soccer in the streets and visited each other’s homes in the city’s Second District. They discussed the terror occurring following the Anschluss, Nazi Germany’s 1938 annexation of Austria, when Jews around them were beaten and sent to prison, some even committing suicide. The horrors reinforced their commitment to living in the Land of Israel.

Krempel fulfilled his dream in April 1939, sent by his parents to join his older brother, Walter. Robert Krempel soon Hebraicized his name, becoming Yeshayahu Karmiel.

Seventy-three years after last seeing his friend, Karmiel, now 86, wanted to know what became of Kelman. He recently took out newspaper notices, contacted the Jewish Agency for Israel, wrote to acquaintances in Belgium and was interviewed on the Israeli “Hamador L’chipus Krovim” (Searching for Relatives Bureau) radio program.

Karmiel remembers Kelman’s family moving to Belgium, but he stopped receiving letters from his friend in early 1940, when the Nazis invaded that country. He didn’t know whether the Kelmans made it to the United States as the parents had planned, were deported to concentration camps or survived the war.

On Wednesday, “Seeking Kin” found Kelman, 85. He had reached New York as a 13-year-old and, using his secular name, Herbert, went on to become a noted sociologist at Harvard University, specializing in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Kelman said he plans to meet Karmiel on a visit to Israel later this year.

“It’s really amazing after all these years,” Kelman said of being found. “Unfortunately, I don’t remember him. I feel bad; I wish I did. But everything matches up, and I can see that the search is legitimate.”

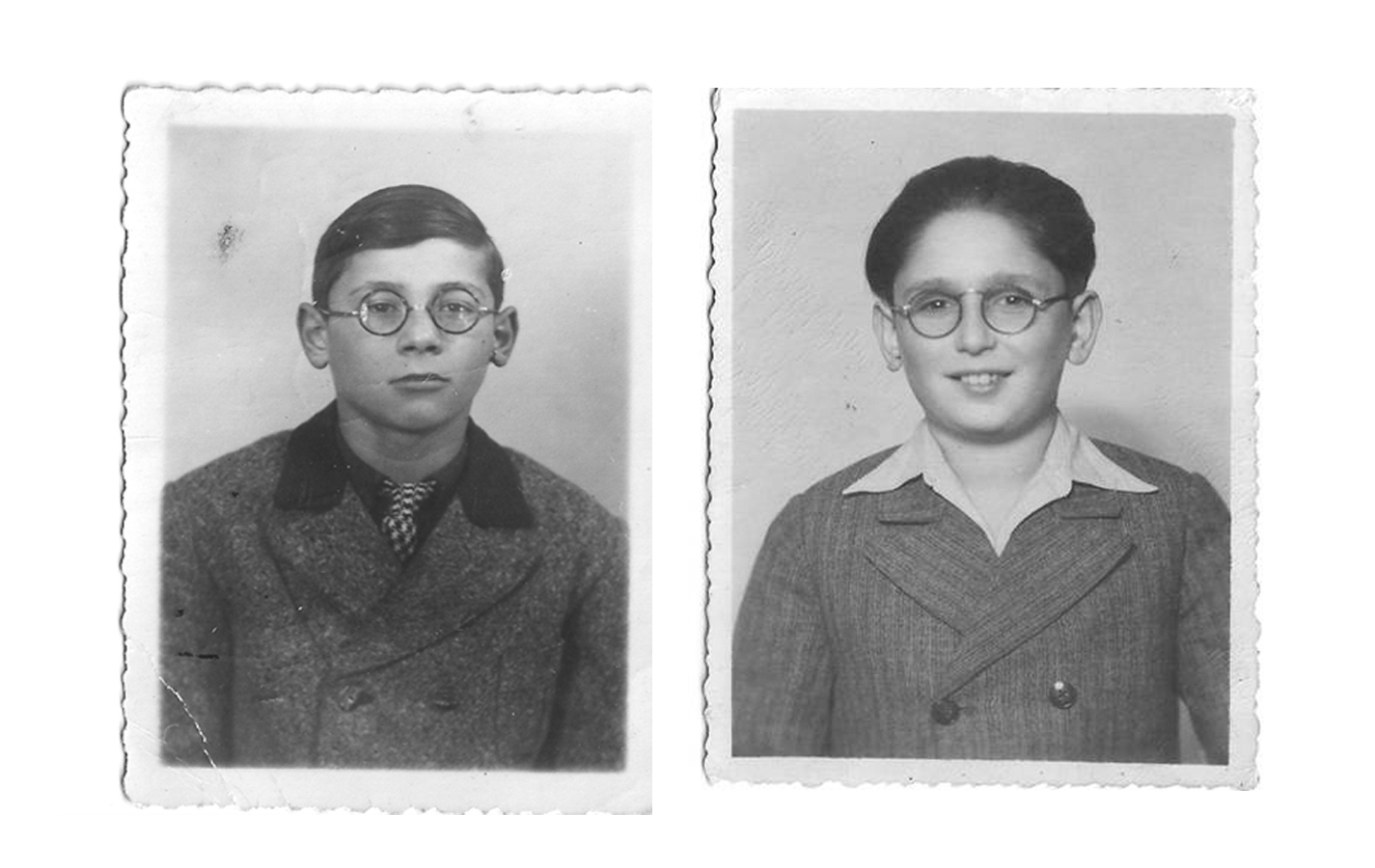

After viewing the two photographs that Karmiel had provided to “Seeking Kin,” Kelman said the image of Karmiel looks familiar.

“I have the feeling that I may have this picture – or some other picture of Robert Krempel – somewhere among my old photographs,” he said.

Karmiel, meanwhile, is delighted about the prospect of seeing his childhood buddy.

“I’m so excited. I’m eager to see him and, in the meantime, to speak or exchange letters,” said Karmiel, a resident of Jerusalem’s German Colony who with his wife, Chava, has four children, 25 grandchildren and 31 great-grandchildren. Before the Kelmans left Vienna, he said, the boys exchanged photographs. “To Yeshayahu, forever,” Kelman wrote on the back of his picture.

Karmiel recalls Kelman as a “very nice” boy who wore eyeglasses and attended Chayes Gymnasium, a Jewish school.

All these years, Karmiel assumed that their correspondence stopped because the Nazis invaded Belgium on May 10, 1940. By then, though, Kelman already had been living in New York a month. His parents, Leo and Antonia (who later went by Lea), soon established a small grocery store near their new home in Brighton Beach, Brooklyn.

The Kelmans — including Herbert’s older sister, Esther Ticktin, who now lives in Washington, D.C. — had fled Austria for Antwerp in late March or early April 1939. They benefited from Belgium’s welcoming of thousands of Jewish refugees, including many who, like them, entered the country illegally.

Peter Black, a senior historian at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, says the measure of Belgium “being very generous in terms of granting asylum to Jews” following Hitler’s rise to power in 1933 is the inability to pinpoint its estimated Jewish population in 1940. From 52,000 to 90,000, Belgium represented “the largest range in Western Europe, without question,” he said.

Belgium’s hospitality to Jewish refugees is “something that often gets forgotten,” Black added.

After their U.S. entry was approved, the Kelmans left Belgium by train in late March 1940. From the port of St. Nazaire, France, they boarded the SS Champlain that reached New York on April 8 of that year. On its very next voyage, a German U-boat sank the Champlain.

“I have very good memories of Vienna. I go back often,” Kelman said. A few years ago, he and his wife, Rose, visited the store in central Vienna where his parents, aunt and uncle ran a fabrics business. The store had been confiscated following the infamous pogrom that the Germans dubbed Kristallnacht. It’s now a gambling parlor.

Karmiel retains the last letter Kelman sent him.

“I can tell you that after two years of waiting, we’re traveling to America,” Kelman wrote in German. “Our friends apparently reached the Land of Israel. Please give them regards: Lidi, the Teitler brothers and Yehuda. How is your brother? Also, give regards to friends Epstein and Traum. L’hitraot [Until we see each other] in Israel. Yours, Chanoch.”

Kelman’s sister added a few lines below. The letter is undated, but the one it came with was written on March 11, 1940. It was from Karmiel’s widowed mother, Rose. With wartime mail service nonexistent between prestate Israel and Austria, Kelman had served as the conduit for Karmiel’s correspondence with Rose.

The March 11 letter was the last one that Karmiel received from his mother. She was sent to the Riga ghetto in February 1942. Karmiel assumes that she was killed there.

If you would like “Seeking Kin” to write about your search for long-lost relatives and friends, please include the principal facts and your contact information in a brief email to Hillel Kuttler at seekingkin@jta.org. “Seeking Kin” is sponsored by Bryna Shuchat and Joshua Landes and family in loving memory of their mother and grandmother, Miriam Shuchat, a lifelong uniter of the Jewish people.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.