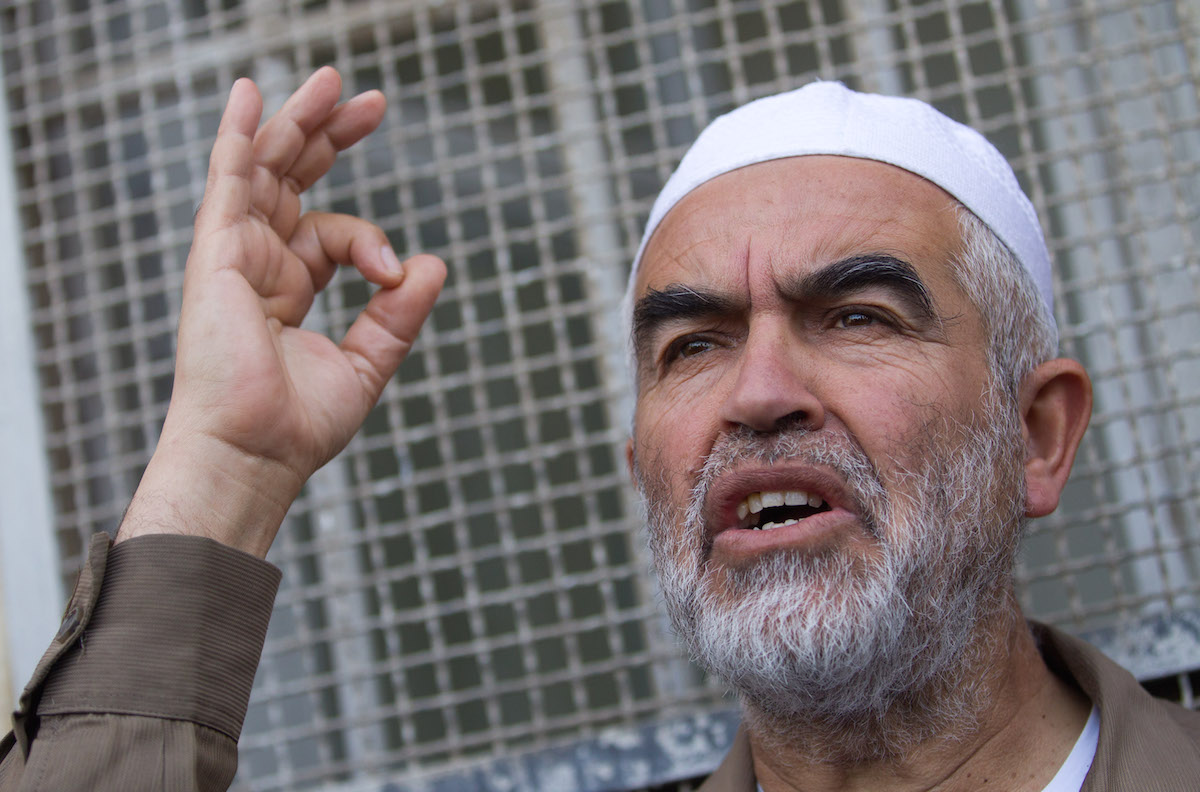

Raed Salah, leader of the northern branch of the Islamic Movement, in Jerusalem, March 26, 2015. (Miriam Alster/Flash90)

TEL AVIV (JTA) – In assigning blame for the recent wave of violence in Israel, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has turned to the usual suspects – Hamas and the Palestinian Authority.

But he has also accused a lesser-known group that operates within Israel’s borders: the Islamic Movement, a religious political group and social service organization.

Netanyahu has seized on the inflammatory rhetoric of the movement’s northern branch, which claims the Al-Aqsa mosque in Jerusalem is “in danger” and has funded protest groups that harass Jewish visitors to the site. Netanyahu has blamed the movement’s rhetoric for inciting the attacks and is seeking to formally ban its activity.

Here’s what the movement does, what it believes about the Temple Mount and why it might be difficult to ban.

What is the Islamic Movement?

The Islamic Movement is a political organization, religious outreach group and social service provider rolled into one. Formed in the 1970s, the movement’s overarching goal is to make Israeli Muslims more religious and owes much of its popularity to providing services often lacking in Israel’s Arab communities. Today the group runs kindergartens, colleges, health clinics, mosques and even a sports league – sometimes under the same roof.

“Their popularity stems from the fact that they had, in every place, changed the face of the local village or town,” said Eli Rekhess, the Crown Chair in Middle East Studies at Northwestern University. “It’s this combination that underlies the Islamic Movement’s formula.”

READ: Why Israelis are fearing a third intifada

The movement split two decades ago. One faction, known as the southern branch, began fielding candidates for Israel’s Knesset in 1996 and now is part of the Joint List, an alliance of several Arab-Israeli political parties. Three of the Joint List’s 13 current Knesset members are part of the movement.

The more hardline northern branch rejects any legitimization of Israel’s government and has called on its adherents to boycott elections. The branches now operate essentially as two separate organizations.

The ‘Al-Aqsa is in danger’ conference

The movement’s northern branch is in Netanyahu’s sights now for its aggressive advocacy for Islamic control over the Temple Mount, the Jerusalem shrine known to Muslims as the Noble Sanctuary. The branch’s leader, Raed Salah, has called on his followers to “redeem” the mount, which houses the Al-Aqsa mosque, from purported Israeli aggression.

Every year, Salah hosts a conference titled “Al-Aqsa is in danger,” and has promoted the idea — hotly disputed by Israeli officials — that Israel seeks to change the status quo at the site.

The movement also funds a group called the Mourabitoun, whose protests against Jewish visitors at the Temple Mount have occasionally turned violent. On Sept. 9, Israel banned the group from the mount, sparking the riots that preceded the current wave of attacks. Salah has accused Netanyahu of declaring war on the mosque.

An offshoot of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood

Netanyahu also sees the group as something of an Islamist fifth column within Israel. The movement, according to Haifa University’s Nohad Ali, is an ideological offshoot of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood, as is Hamas, the militant group that controls Gaza and is considered a terrorist organization by the United States.

Though they all share the same principles and operate similarly — Hamas and the Muslim Brotherhood also operate educational and social service programs in addition to their political activities — the Islamic Movement has no organizational relation to the others. Rekhess says remaining separate gives the movement a niche within Israel. And Ali says keeping its distance from Hamas helps the movement avoid prosecution. Which is why …

There’s not much Netanyahu can do to ban it.

Salah has served prison time for assaulting an Israeli police officer and is appealing a conviction for incitement, but several experts say Netanyahu will be hard-pressed to outlaw the whole group for incitement to violence. Its official pronouncements are too ambiguous to qualify as illegal, they say.

“They don’t call for violence,” Ali said. “They know that use of violence will cause the destruction of the movement. I’m not saying they’re angels or that they oppose violence, [but] they’re using vague concepts.”

Outlawing the group could also spark a broad backlash in Israel’s Arab sector. Knesset member Talab Abu Arar, a member of the movement’s southern branch, said he could view any ban on the group as an attack on Arab-Israelis as a whole.

“The Islamic Movement includes most of the Arab public in Israel,” Abu Arar told JTA. “Outlawing it, you could say, is outlawing the entire public from the land.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.