You wouldn’t know it from all the breathless articles about the wide new world of Cuba travel, but tourism in Castro’s paradise is still illegal in the eyes of Uncle Sam.

Yes, visiting our Cold War nemesis is easier lately. With the resumption of diplomatic relations and the loosening of restrictions on activity between the two countries, highly motivated Americans can now explore Cuba without complicated maneuvers through a third country. But the 55-year-old trade embargo is still in place; tourism is officially illegal, so you can’t plan a week on the beach.

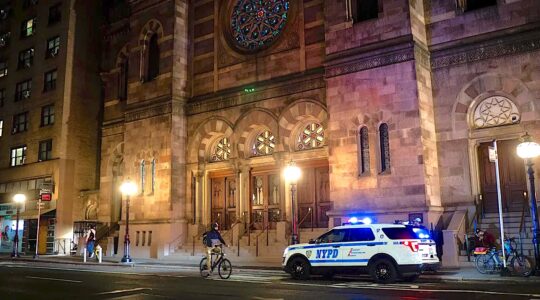

Most American visitors will obtain the required visa through a guided program, since the Treasury Department requires American travel to Cuba to fall into one of a half-dozen non-tourism categories — including family visits, humanitarian and research projects, arts or religious exchanges, and so-called people-to-people travel. These categories include the small but proliferating niche of Jewish travel to Cuba.

People-to-people trips — in which Americans follow a highly structured itinerary of cultural and educational engagement with their Cuban counterparts — are the legal basis for many of the new tour offerings, which are licensed through the U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (known as OFAC; its updated guide to the legalities of Cuba travel can be found at treasury.gov/resource-center/sanctions/Programs/Documents/cuba_faqs_new.pdf).

To learn more, I spoke recently with Arthur Berman, a pioneer of American Cuba travel and as of last year vice president of the new Latin America and Cuba division he created at Central Holidays, a venerable New Jersey-based tour operator.

Drawing on Berman’s long experience with people-to-people programs in Cuba, Central last year launched five of them — including L’Chaim Cuba, a nine-day tour of the Jewish communities in Havana and Cienfuegos. The $3,999 trip includes visits to Ashkenazic and Sephardic synagogues, the UNESCO World Heritage city of Trinidad, a cigar factory and Hemingway’s home.

And it’s one of few tours for which participants are encouraged to overpack. Unlike tourists in France or Italy, those heading to Cuba typically bring along baby clothes, toothpaste, Tylenol and other everyday items to donate, since the embargo has made such essentials difficult to buy. In Havana, Berman’s guests tour the Jewish pharmacy, which operates more like a food pantry: foreigners contribute products that are distributed free to local residents.

That personal engagement is what distinguishes person-to-person travel. It’s also the kind of experience unique to this moment — an opportunity, Berman said, that has an expiration date.

“It’s like going into a time capsule, going back 55 years,” he explained, citing a common sentiment among Americans determined to get there before the diluting effect of foreign influence. “Everywhere else you go, it’s today — London, Paris, even in Rio de Janeiro; it’s poor, but you’re living in today’s world.”

But in Havana, “there’s nothing American. There’s no McDonald’s,” nor any of the other chains that have homogenized the downtowns of most foreign capitals, Berman noted. Instead, visitors explore cobblestone streets lined with restored colonial buildings; make friends over local rum at family-run restaurants called paladars; and enjoy the same views that inspired Hemingway. “People are going now because that’s what they want to see,” said Berman. “In five or 10 years, it’ll be like St. Martin.”

For now, Cuba’s distinctiveness comes with challenges of the sort unfamiliar to St. Martin tourists. To begin with, there is the well-documented shortage of hotel rooms, especially those with the standards American travelers expect. Those four- and five-star lodgings constitute less than a third of Havana hotels, and the recent explosion of Cuba tours has complicated matters.

“It’ll get better eventually,” said Berman, though he noted that Cuba’s tourism infrastructure has been severely overburdened in the two years since President Obama’s diplomatic overture. As Americans clamored to visit, top hotels initially triple-booked and demanded the names of individuals in tour groups — along with payment — a year in advance. “And in Cuba, if the five-star bumps you, they bump you to a two-star,” Berman added with a shudder. (He assured me that Central’s rooms are reserved through 2017, thanks to longstanding relationships with local operators.)

Support the New York Jewish Week

Our nonprofit newsroom depends on readers like you. Make a donation now to support independent Jewish journalism in New York.

The shortages may seem odd, considering that America’s embargo has not prevented Canadians and Europeans from vacationing on Cuban beaches over the years. But as Berman explained, beach resorts are one thing; Americans look to Cuba as a cultural experience, so hotels are lacking in precisely the urban locales where demand is now highest.

And that’s just once you get there. Reaching the island remains an expensive challenge; while commercial airlines are planning Cuba routes, the only flights to Havana currently are on expensive charter planes. Options are expected to expand throughout 2016, but for now, the 35-minute charter flight from Miami to Havana costs between $500 and $700.

All of which explains why weeklong tours typically cost $4,000-$5,000 or more — and why Berman takes care of every detail for his guests, from meals and transportation to visas and bilingual tour guides. The payoff is worthwhile for those eager to see Cuba in what many consider its pre-capitalist sweet spot. “We tell people it’s not a vacation,” said Berman. “It’s an experience.”

You wouldn’t know it from all the breathless articles about the wide new world of Cuba travel, but tourism in Castro’s paradise is still illegal in the eyes of Uncle Sam.

Yes, visiting our Cold War nemesis is easier lately. With the resumption of diplomatic relations and the loosening of restrictions on activity between the two countries, highly motivated Americans can now explore Cuba without complicated maneuvers through a third country. But the 55-year-old trade embargo is still in place; tourism is officially illegal, so you can’t plan a week on the beach.

Most American visitors will obtain the required visa through a guided program, since the Treasury Department requires American travel to Cuba to fall into one of a half-dozen non-tourism categories — including family visits, humanitarian and research projects, arts or religious exchanges, and so-called people-to-people travel. These categories include the small but proliferating niche of Jewish travel to Cuba.

People-to-people trips — in which Americans follow a highly structured itinerary of cultural and educational engagement with their Cuban counterparts — are the legal basis for many of the new tour offerings, which are licensed through the U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (known as OFAC; its updated guide to the legalities of Cuba travel can be found at treasury.gov/resource-center/sanctions/Programs/Documents/cuba_faqs_new.pdf).

To learn more, I spoke recently with Arthur Berman, a pioneer of American Cuba travel and as of last year vice president of the new Latin America and Cuba division he created at Central Holidays, a venerable New Jersey-based tour operator.

Drawing on Berman’s long experience with people-to-people programs in Cuba, Central last year launched five of them — including L’Chaim Cuba, a nine-day tour of the Jewish communities in Havana and Cienfuegos. The $3,999 trip includes visits to Ashkenazic and Sephardic synagogues, the UNESCO World Heritage city of Trinidad, a cigar factory and Hemingway’s home.

And it’s one of few tours for which participants are encouraged to overpack. Unlike tourists in France or Italy, those heading to Cuba typically bring along baby clothes, toothpaste, Tylenol and other everyday items to donate, since the embargo has made such essentials difficult to buy. In Havana, Berman’s guests tour the Jewish pharmacy, which operates more like a food pantry: foreigners contribute products that are distributed free to local residents.

That personal engagement is what distinguishes person-to-person travel. It’s also the kind of experience unique to this moment — an opportunity, Berman said, that has an expiration date.

“It’s like going into a time capsule, going back 55 years,” he explained, citing a common sentiment among Americans determined to get there before the diluting effect of foreign influence. “Everywhere else you go, it’s today — London, Paris, even in Rio de Janeiro; it’s poor, but you’re living in today’s world.”

Support the New York Jewish Week

Our nonprofit newsroom depends on readers like you. Make a donation now to support independent Jewish journalism in New York.

But in Havana, “there’s nothing American. There’s no McDonald’s,” nor any of the other chains that have homogenized the downtowns of most foreign capitals, Berman noted. Instead, visitors explore cobblestone streets lined with restored colonial buildings; make friends over local rum at family-run restaurants called paladars; and enjoy the same views that inspired Hemingway. “People are going now because that’s what they want to see,” said Berman. “In five or 10 years, it’ll be like St. Martin.”

For now, Cuba’s distinctiveness comes with challenges of the sort unfamiliar to St. Martin tourists. To begin with, there is the well-documented shortage of hotel rooms, especially those with the standards American travelers expect. Those four- and five-star lodgings constitute less than a third of Havana hotels, and the recent explosion of Cuba tours has complicated matters.

“It’ll get better eventually,” said Berman, though he noted that Cuba’s tourism infrastructure has been severely overburdened in the two years since President Obama’s diplomatic overture. As Americans clamored to visit, top hotels initially triple-booked and demanded the names of individuals in tour groups — along with payment — a year in advance. “And in Cuba, if the five-star bumps you, they bump you to a two-star,” Berman added with a shudder. (He assured me that Central’s rooms are reserved through 2017, thanks to longstanding relationships with local operators.)

The shortages may seem odd, considering that America’s embargo has not prevented Canadians and Europeans from vacationing on Cuban beaches over the years. But as Berman explained, beach resorts are one thing; Americans look to Cuba as a cultural experience, so hotels are lacking in precisely the urban locales where demand is now highest.

And that’s just once you get there. Reaching the island remains an expensive challenge; while commercial airlines are planning Cuba routes, the only flights to Havana currently are on expensive charter planes. Options are expected to expand throughout 2016, but for now, the 35-minute charter flight from Miami to Havana costs between $500 and $700.

All of which explains why weeklong tours typically cost $4,000-$5,000 or more — and why Berman takes care of every detail for his guests, from meals and transportation to visas and bilingual tour guides. The payoff is worthwhile for those eager to see Cuba in what many consider its pre-capitalist sweet spot. “We tell people it’s not a vacation,” said Berman. “It’s an experience.”

Update: On Tuesday, March 15, the U.S. government announced a lifting of the ban on individual travel to Cuba by Americans under the people-to-people program. While tourism is still officially illegal, Americans will no longer have to join an organized tour to visit the country. They are still required to have a full itinerary of meaningful cultural exchange, but given the vagueness and complexity involved in assessing individuals’ daily schedules abroad, the new system amounts to a de facto legalization of tourism for independent travelers. Would-be visitors still face considerable challenges – most notably lodging shortages and limited flight options – that will make organized tours the most convenient option in the near future.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.