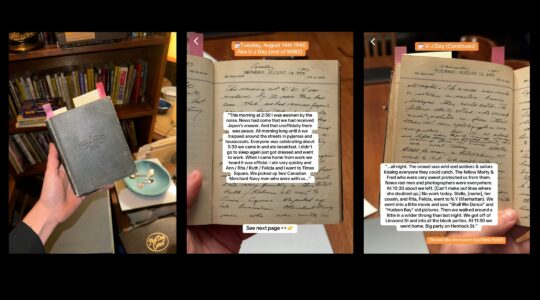

Steve Low, center, the director of the Flint Jewish Federation, takes a delivery of food from a kosher deli in Indianapolis.

Flint, Mich. — At 86, Jeanne Aaronson is blind and lives alone, but she has seen a lot over the years. She lived in Flint when it was a manufacturing powerhouse, a center of the automotive business and a symbol of American industrial might and ingenuity.

She lived through the city’s decline in the 1970s and ’80s as the auto factories closed and the population decamped for better opportunities elsewhere. And more recently, she witnessed the beginning of its revival, with the opening of new businesses and a slew of brewpubs and coffee shops on Saginaw Street.

Now Aaronson is living through yet another difficult period in Flint history, as the city copes with toxic levels of lead in its drinking water that has made Flint a national example of failed governance. Like all the residents here, Aaronson is surviving on bottled water, which she must even feed to her elderly dog.

“Am I ticked? You bet I’m ticked,” Aaronson told JTA. “I’m ticked at the stupidity of our governor for appointing that emergency manager who decided to save a few bucks by poisoning us. Just stupid. I’m ticked at everyone from the very top to the very bottom. Except our new mayor. Mayor Weaver’s doing a good job. But otherwise, I have no faith. None at all.”

Flint has been facing a public health emergency since April 2014, when the city, under the direction of a state-appointed emergency financial manager, began to use the Flint River as its water source. The city used to get its water from Detroit’s water system, which relied on Lake Huron and the Detroit River as water sources. After the switch, the state chose not to use phosphates as an anti-corrosion agent, which caused lead to leach from old pipes into the drinking water.

The crisis was featured prominently in the Democratic presidential debate in early March, with both candidates addressing the water situation in the opening minutes. Clinton described meeting mothers terrified for their children. Sanders spoke of his broken heart at hearing of a child now developmentally delayed as a result of lead poisoning.

“Whether this happened because of sins of omission or sins of commission doesn’t matter,” said Steve Low, the director of the Flint Jewish Federation, which has been helping deliver bottled water to local residents. “It doesn’t make the poisoning of Flint’s water supply any less heinous.”

Aaronson’s is one of only 66 identified Jewish households left in Flint, a city of 100,000 people 60 miles northwest of Detroit. About 200 more Jewish families live in the Flint area but outside the city limits, where the water hasn’t been affected.

Like Aaronson, many Jews in Flint are elderly, and they’ve been particularly battered by the crisis. For some with arthritic hands, merely opening the bottled water that is now an essential commodity here can be a challenge. Others have had difficulty getting assistance because they don’t have Internet access or are hesitant about opening their door to strangers in a high-crime city.

“For me, this is one giant pain. And yes, I am plenty angry. But I can take care of myself,” said Sue Ellen Hange, 61, a member of Flint’s Temple Beth El who got skin rashes from showering in the contaminated water. “I can’t imagine what it’d be like to be homebound and dealing with this.”

The Flint Jewish community has responded with support both moral debates and material. To ease the fears of the city’s older Jews, familiar faces from the federation’s senior services division often accompany the water delivery. Two of Flint’s synagogues have held informational meetings and offered special prayers for healing. Synagogue social action committees have also reached out to local residents to remind them they’re not alone.

Support the New York Jewish Week

Our nonprofit newsroom depends on readers like you. Make a donation now to support independent Jewish journalism in New York.

Support has also come from further afield. The Metro Detroit Federation made a cash contribution of an undisclosed sum to the community. Several Detroit-area congregations joined forces and made the trek 60 miles north with a truck full of water. The Yad Ezra Food Pantry, a group of Detroit-area Chabad houses and the Jewish Federation in Toledo, Ohio, also made water donations.

From Indianapolis, Shapiro’s Deli sent a complete Shabbat meal for 150 in January, including corned beef, pastrami, knishes, chicken soup with matzah balls and even Dr. Brown’s soda. The Jewish relief effort even reached as far as California, where San Francisco chocolatier and Flint native Chuck Siegel sent over an array of sweets and beloved Flint nostalgia foods like Vernors ginger ale and Koegel’s hot dogs. In Los Angeles, Flint native and Hollywood publicist Howard Bragman helped stage the Hollywood Helps Flint fundraiser on Feb. 21, which has so far raised $33,000 for the city.

“We may have left Flint,” Bragman said at the fundraiser, “but Flint never left us.”

The crisis comes at a particularly unfortunate moment for Flint. After decades of mounting poverty and crime, the city had recently begun to rebound. Businesses as varied as a small maker of hip eyeglass frames to corporate giants had set up shop in the city. Renovated dowager buildings downtown are now trendy loft apartments. The Michigan State University Medical School opened a new campus downtown, and Kettering University and the University of Michigan-Flint both dramatically expanded their footprints in the city.

“If it’s possible to see the good in this,” Low said, “it’s that the water crisis threw a big net over the community and has drawn us together. Going back to the 1950s, Flint’s Jews and the African-American community have always worked together. Lately, not so much. But the water has rekindled some of those passions we both share for social justice.”

The crisis has also drawn the Jewish and Hispanic communities together. At a recent meeting at Flint’s Temple Beth El, congregant Melba Lewis pointed out that many local Hispanics are undocumented and are loath to open their doors to uniformed officers to distribute water. The synagogue wound up partnering with a large Hispanic church to distribute a pallet of water to the church for distribution.

But whatever silver linings Flint residents might find in the crisis, their faith in elected officials seems unlikely to be restored anytime soon. Low saw signs of racism in the crisis, likening the decisions that created the crisis in this majority-African American city to other government moves — like the Supreme Court’s 2013 ruling invalidating a key provision of the Voting Rights Act and the nationwide trend to implement voter identification laws — that have disproportionately impact on minorities. Aaronson simply feels abandoned.

“I was listening to the Republican debate [in March], 70 miles from here in Detroit, and there’s one question about the water,” she said last week. “One question! That’s so wrong. It should have been on the top of the list.”

David Stanley is a writer based in Flint, Mich. He served as a member of the Flint Jewish Federation board of trustees from 1990 to 1992.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.