AMSTERDAM (JTA) — I used to think I had a pretty good understanding of what it means to be Jewish in Belgium.

A longtime observer of that polarized binational country, whose dysfunctions and successes often reflect those of the European Union headquartered in its capital, Brussels, I have family ties there and am fluent in the local languages.

But I had to readjust my understanding of Belgian Jewry’s circumstances this month while reporting on a local Catholic school’s stated pride in and support for a teacher who had published anti-Semitic caricatures, and who recently won a cash prize at Iran’s Holocaust mockery cartoon competition.

Shielded by education officials’ wall of silence and celebrated in mainstream Belgian media as a champion of free speech, Luc Descheemaeker was able to pass off anti-Semitic imagery as legitimate criticism of Israel in a way that I had thought impossible in an established Western democracy in the heart of Europe.

As Descheemaeker’s advocates circled the wagons around him — his school praised him as working to preserve, not distort, the memory of the Holocaust — I saw firsthand how anti-Israel vitriol has mainstreamed classic anti-Semitism in a country where Jews are leaving partly because they feel their children can no longer comfortably attend the public schools.

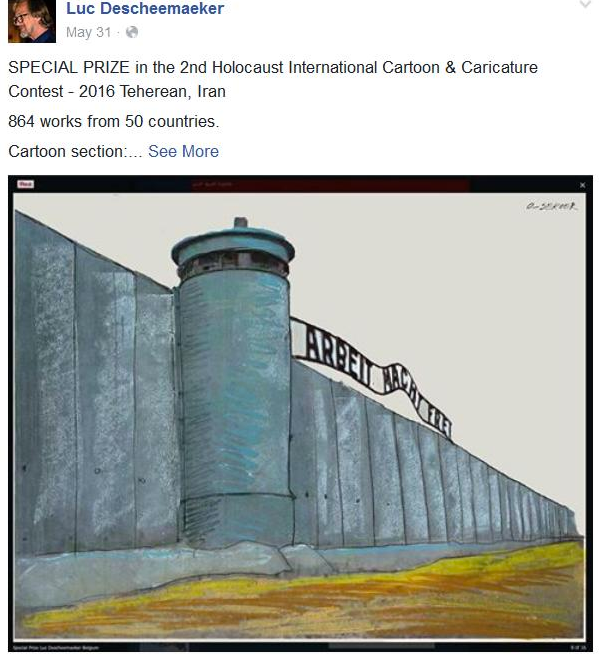

My Belgian eye opener began with a post on The New Antisemite blog, which tracks anti-Jewish sentiment in Europe. It said the vice director of the Sint Jozef Institute high school near Antwerp had told a Belgian Jewish publication that she was “very proud” of Descheemaeker after he won $1,000 and a special mention at the Second International Holocaust Cartoon Contest in Tehran.

Luc Descheemaeker shared news of his prize at the Iranian Holocaust cartoon contest in May on his Facebook page. (Facebook)

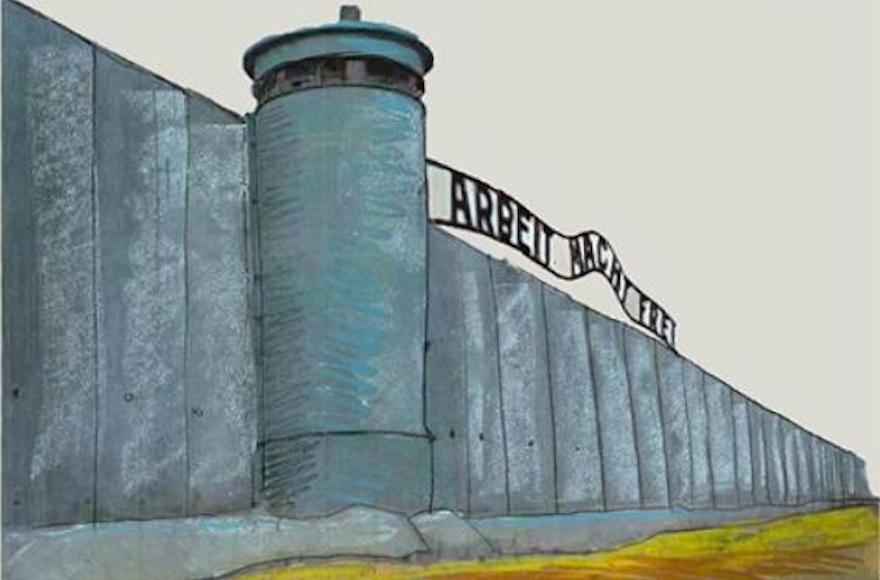

The winning entry by Descheemaeker, a plastic arts teacher who retired this year, was a drawing of the words “Arbeit Macht Frei” over Israel’s security barrier along the West Bank. The German sentence, which means “work sets you free,” was featured on a gate of the Auschwitz Nazi death camp in Poland.

Previously, I found, Descheemaeker had published at least two cartoons that used classically anti-Semitic imagery. In one, an Orthodox Jew waits to bludgeon a peaceful Arab baby and his mother with a giant Star of David. In another, the Jew is waiting to startle a jihadist who is holding a shopping bag while wearing an explosives vest — presumably so she blows herself up.

The Forum of Jewish Organizations of Belgium’s Flemish Region condemned Descheemaeker’s Arbeit Macht Frei cartoon as “an example of modern anti-Semitism” and his earlier work featuring depictions of Jews as “classically anti-Semitic.”

Additionally, the cartoon contest in which he participated was decried as anti-Semitic by UNESCO, Germany and the United States, among others.

And finally, comparing Israeli policies to those of Nazi Germany is an example of anti-Semitism, according to the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance – an intergovernmental organization with 31 member states, including Belgium.

I was skeptical of the blog’s report about the school’s endorsement of Descheemaeker because Western European educational institutions rarely seek to associate themselves with his brand of imagery.

Belgium has made discernible progress in recent years in coming to terms with the Holocaust-era complicity of its authorities and population. Surely, I thought, Descheemaeker would not get support and praise from a prestigious Catholic school there.

My first surprise was the reply I received from the school to my query over Descheemaeker. Yes, confirmed the school director Paul Vanthournout – “we are proud of Luc Descheemaeker,” though not, per se, over his winning the award in Iran or his cartoons, he said. Vanthournout declined to comment on these activities, which he said had nothing to do with Descheemaeker’s teaching position, but assured me that Descheemaeker “is not an anti-Semite.”

As proof, the school director cited an award that Descheemaeker won in 2002 from Belgium’s Queen Paola for staging a student show based on Art Spiegelman’s Holocaust memoir “Maus.”

I wanted to see whether the school can get away with defending the maker of blatant anti-Semitic imagery by claiming to be neutral on its celebrated teacher’s extracurricular activities. So I repeatedly queried the board of education, the royal house, the Queen Paola Foundation, the municipality where the school is located and Belgium’s federal center against discrimination. I received one written response, from the foundation, saying it had no comment for me.

This see-no-evil approach from government offices in a country whose leaders often declare a zero-tolerance attitude to anti-Semitism surprised me. But the real shock was the response from the Belgian media to JTA’s coverage of the affair.

De Morgen, one of Belgium’s largest and best-respected dailies, ran an article that omitted reference to Descheemaeker’s caricatures of Jews. It described the Iranian competition as a “controversial” affair “themed on the Holocaust,” which the paper said was instituted as a statement about freedom of expression following the publication of insulting caricatures of the Prophet Muhammad in Denmark.

(UNESCO, the cultural arm of the United Nations, had called the contest “a mockery of the genocide of the Jewish people.”)

Descheemaeker, who is described in the paper as an internationally acclaimed caricaturist, is quoted as saying in reaction to the uproar created by his work: “There is still such a thing as freedom of expression.”

Knack, a popular news site, took the same editorial line.

(Descheemaeker did not respond to JTA requests for an interview sent through his school, on social media and via email.)

Confused, I reached out to Joel Rubinfeld, founder of the Belgian League Against Anti-Semitism and former president of the CCOJB umbrella group of French-speaking Belgian Jewish communities. I wanted to know whether Belgian education officials were more tolerant of expressions of anti-Semitism than their counterparts from other Western European countries.

“It’s a problem,” he said. “We’ve encountered a number of cases where schools did not take the necessary measures when Jewish pupils were targeted in anti-Semitic bullying, for example.”

A teacher who last year told a Jewish high school student, “We should put you all on freight wagons,” was allowed to keep his job following an internal inquiry. It ended with him apologizing while denying any anti-Semitic intent in the first place.

Cases involving anti-Semitic abuse among students are regularly ignored at Belgian schools, “which don’t apply the measures necessary to make these cases stop,” Rubinfeld said.

One student was forced to leave his public school and was enrolled in a private Jewish one last year following harassment, which included a threat to “break his skull” if he showed support for Israel. Also last year, the Belgian media reported on the online shaming by classmates of a pro-Israel high school student. He also left the public education system for a Jewish school.

As Belgian Jews continue to grapple with the anti-Semitism problem in their country — in 2014, a suspected jihadist was arrested for the shooting deaths of four people at the Jewish museum in Brussels — a growing number are deciding to look for a new home.

Last year, 287 Jews immigrated to Israel from Belgium, which has a Jewish population of about 40,000. It was the highest figure recorded in a decade. From 2010 to 2015, an average of 234 Belgian Jews made aliyah annually — a 56 percent increase over the annual average of 133 new arrivals from Belgium in 2005-2009, according to Israeli government data.

“In Belgium, the choice for Jews is often between abuse or ghettoization,” Rubinfeld said. “It’s not surprising that a growing number of Belgian Jews are finding alternatives to both.”

RELATED:

When Brussels stopped being my refuge from terror in Israel

Senior Brussels rabbi: Belgian authorities know nothing about security

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.