This story is sponsored by the Israel Cancer Research Fund.

NEW YORK — As if Jews don’t have enough to worry about.

Geopolitical threats to the Jewish people may wax and wane, but there’s another lethal danger particular to the Jewish people that shows no signs of disappearing anytime soon: cancer.

Specifically, Jews are at elevated risk for three types of the disease: melanoma, breast cancer and ovarian cancer. The perils are particularly acute for Jewish women.

The higher prevalence of these illnesses isn’t spread evenly among all Jews. The genetic mutations that result in higher incidence of cancer are concentrated among Ashkenazim — Jews of European descent.

“Ashkenazim are a more homogenous population from a genetic point of view, whereas the Sephardim are much more diverse,” said Dr. Ephrat Levy-Lahad, director of the Medical Genetics Institute at Shaare Zedek Medical Center in Jerusalem.

But there is some hope. Susceptible populations can take certain precautions to reduce their risks. Recent medical advances have made early detection easier, significantly lowering the fatality rates from some cancers. Cheaper genetic testing is making it much easier for researchers to discover the risk factors associated with certain cancers. And scientists are working on new approaches to fight these pernicious diseases – especially in Israel, where Ashkenazi Jews make up a larger proportion of the population than in any other country.

Understanding risk factors and learning about preventative measures are key to improving cancer survival rates. Here’s what you need to know.

Melanoma

Melanoma is the deadliest type of skin cancer, representing some 80 percent of skin cancer deaths, and U.S. melanoma rates are on the rise. It’s also one of the most common forms of cancer in younger people, especially among women.

Just a decade ago, Israel had the second-highest rate of skin cancer in the world, behind Australia. One reason is that Israel has a lot of sun. Some credit better education about the dangers of sun exposure for helping reduce Israel’s per capita skin cancer rate, now 18th in the world.

But the sun isn’t the whole story. Jews in Israel have a higher incidence of melanoma than the country’s Arab, non-Jewish citizens.

What makes Jews more likely to get skin cancer than others?

It’s a combination of genetics and behavior, according to Dr. Harriet Kluger, a cancer researcher at Yale University. On the genetics side, Ashkenazi Jews — who comprise about half of Israel’s Jewish population — are significantly more likely to have the BRCA-2 genetic mutation that some studies have linked to higher rates of melanoma.

The other factor, Israel’s abundant sunshine, exacerbates the problems for sun-sensitive Jews of European origin. That’s why Arabs and Israeli Orthodox Jews, whose more conservative dress leaves less skin exposed than does typical secular attire, have a lower incidence of the cancer.

“There are epidemiological studies from Israel showing that secular Jews have more melanoma than Orthodox Jews,” Kluger said.

So what’s to be done?

“Other than staying out of the sun, people should get their skin screened once a year,” Kluger said. “In Australia, getting your skin screened is part of the culture, like getting your teeth cleaned in America.”

You can spot worrisome moles on your own using an alphabetic mnemonic device for letters A-F: See a doctor if you spot moles that exhibit Asymmetry, Border irregularities, dark or multiple Colors, have a large Diameter, are Evolving (e.g. changing), or are just plain Funny looking. Light-skinned people and redheads should be most vigilant, as well as those who live in sunny locales like California, Florida or the Rocky Mountain states.

If you insist on being in the sun, sunscreen can help mitigate the risk, but only up to a point.

“It decreases the chances of getting melanoma, but it doesn’t eliminate the chances,” Kluger warned.

As with other cancers, early detection can dramatically increase survival rates.

In the meantime, scientists in Israel – a world leader in melanoma research – hold high hopes for immunotherapy, which corrals the body’s immune mechanisms to attack or disable cancer. At Bar-Ilan University, Dr. Cyrille Cohen is using a research grant from the Israel Cancer Research Fund to implant human melanoma cells in mice to study whether human white blood cells can be genetically modified to act as a “switch” that turns on the human immune system’s cancer‐fighting properties.

Breast cancer

Breast cancer is already more common in developed, Western countries than elsewhere — likely because women who delay childbirth until later in life and have fewer children do not enjoy as much of the positive, cancer risk-reducing effects of the hormonal changes associated with childbirth.

Ashkenazi Jews in particular have a significantly higher risk for breast cancer: They are about three times as likely as non-Ashkenazim to carry mutations in the BRCA-1 and BRCA-2 genes that lead to a very high chance of developing cancer. One of the BRCA-1 mutations is associated with a 65 percent chance of developing breast cancer. Based on family history, including on the father’s side, the chances could be even higher.

“Every Ashkenazi Jewish woman should be tested for these mutations,” said Levy-Lahad, who has done significant research work on the genetics of both breast and ovarian cancer. Iraqi Jews also have increased prevalence of one of the BRCA mutations, she said.

Some Ashkenazi Jewish women who carry a particular BRCA-1 genetic mutation have a 65 percent chance of developing breast cancer. (Media for Medical/UIG via Getty Images)

Levy-Lahad is collaborating on a long-term project with the University of Washington’s Dr. Mary-Claire King — the breast cancer research pioneer who discovered the BCRA-1 gene mutation that causes cancer — on a genome sequencing study of Israeli women with inherited breast and ovarian cancer genes. The two women are using a grant from the Israel Cancer Research Fund to apply genomic technology to study BRCA-1 and BRCA-2 mutations and their implications for breast cancer risk in non-Ashkenazi women in Israel, who are similar to populations in Europe and the United States.

In a project that is testing thousands of women for deadly cancer mutations, they are also studying how mutations in genes other than BRCA-1 and BRCA-2 impact inherited breast cancer in non-Ashkenazi Jews.

The earlier breast cancer mutations are discovered, the sooner women can decide on a course of action. Some choose to have bilateral mastectomies, which reduce the chances of breast cancer by 90-95 percent. Actress Angelina Jolie famously put a Hollywood spotlight on the issue when she wrote a 2013 op-ed in The New York Times about her decision to have the procedure.

But mastectomies are not the only option. Some women instead choose a very rigorous screening regimen, including more frequent mammograms and breast MRIs.

Early detection is the cornerstone of improving breast cancer survival rates.

“Breast cancer is not nearly as deadly as it once was,” Levy-Lahad said.

Ovarian cancer

Of the three “Jewish” cancers, ovarian cancer is the deadliest.

Linked to the two BRCA mutations common among Jews, ovarian cancer is both stubbornly difficult to detect early and has a very high late-stage mortality rate. Women should be screened for the mutations by age 30, so they know their risks.

In its early stages, ovarian cancer usually has no obvious symptoms, or appears as bloating, abdominal pain or frequent urination that can be explained away by less serious causes. By the time it’s discovered, ovarian cancer is usually much more advanced than most other cancers and may have spread to surrounding organs. If that has occurred, the five-year survival rate drops considerably.

Women with the BRCA mutations have about a 50 percent chance of getting ovarian cancer. The best option is usually to remove the ovaries.

“We put a lot of pressure on women to have their ovaries removed because it’s a life-saving procedure,” Levy-Lahad said.

That doesn’t mean these women can’t have children. The recommendation is that women wait to have the procedure until after they complete child-bearing, usually around the age of 35-40.

Much work still needs to be done on prevention, early detection and treatment of ovarian cancer, but new research shows some promise.

“The exciting thing is that we live in a genomic age, and we have unprecedented abilities to understand the causes of cancer,” Levy-Lahad said. “There’s a whole field that, if you become affected, can look at the genetic makeup of the tumor you have.”

The study of these three “Jewish cancers” are a major component of the work of the Israel Cancer Research Fund, which raises money in North America for cancer research in Israel. Of the $3.85 million in grants distributed in Israel last year by the fund, roughly one-quarter were focused on breast cancer, ovarian cancer or melanoma, according to Ellen T. Rubin, the ICRF’s director of research grants. The organization’s Rachel’s Society focuses specifically on supporting women’s cancer awareness and research.

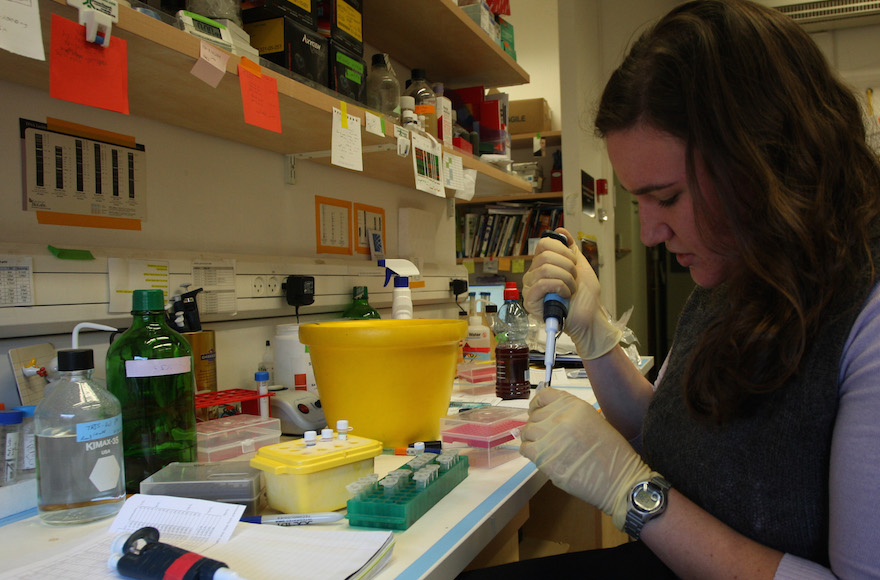

Israel has become a hub for cancer research, including at this lab at the Hebrew University Hadassah Medical School. (Keren Freeman/Flash90)

A significant amount of the organization’s grants is focused on basic research that may be applicable to a broad spectrum of cancers. For example, the group is supporting research by Dr. Varda Rotter of the Weizmann Institute of Science into the role played by the p53 gene in ovarian cancer. P53 is a tumor suppressor that when mutated is involved in the majority of human cancers.

Likewise, Dr. Yehudit Bergman of the Hebrew University Hadassah Medical School is using an ICRF grant to study how the biological mechanisms that switch genes on and off – called epigenetic regulation – operate in stem cells and cancer.

“Only through basic research at the molecular level will cancer be conquered,” said Dr. Howard Cedar of the Hebrew University Hadassah Medical School.

“Hopefully, one day there will be easier and better ways to detect and destroy the cancerous cells that lead to these diseases. But until those research breakthroughs, medical experts say that Jews, as members of a special high-risk category, should make sure they get genetic screenings and regular testing necessary for early detection and prevention.

(This article was sponsored by and produced in partnership with the Israel Cancer Research Fund, which is committed to finding and funding breakthrough treatments and cures for all forms of cancer, leveraging the unique talent, expertise and benefits that Israel and its scientists have to offer. This article was not produced by JTA’s staff reporters or editors.)

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.