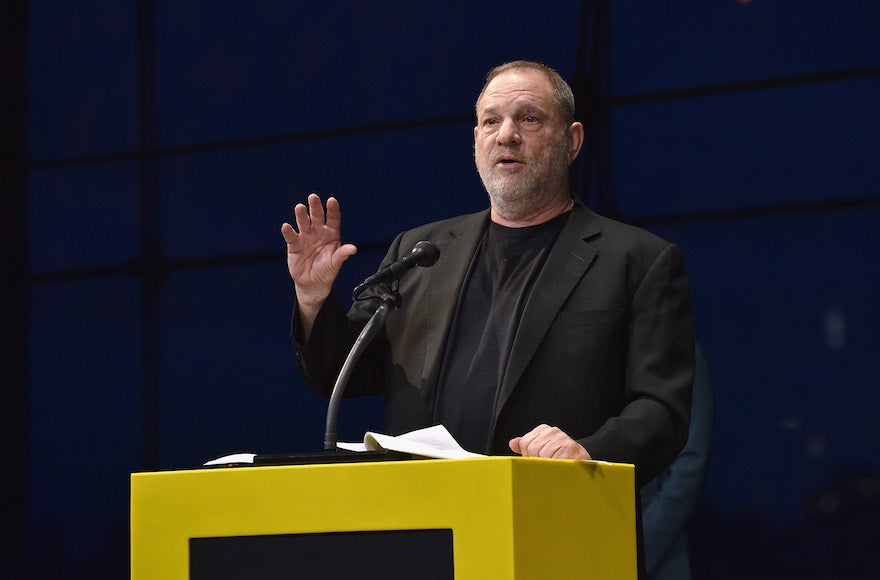

(JTA) — In an interview with The Daily Beast, George Clooney described Harvey Weinstein as a very powerful man with a tendency to hit on young beautiful women over whom he had power. Despite the “rumors” he had heard about Weinstein’s openly predatory behavior, Clooney expressed sincere shock and outrage at the widespread sexual misconduct allegations directed at Weinstein.

Clooney is not alone in this cognitive dissonance. MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow reported that well before articles in The New York Times and the New Yorker quoted dozens of his victims, his colleagues routinely referenced his behavior in public speeches. Everyone knew that Weinstein abused his power, yet the harm he did to his victims was a well-kept secret.

Michelle Obama addressed this dynamic last year in response to the news that then-candidate Donald Trump had been caught on tape bragging about sexual assault. She said that women are drowning in violence and abuse and disrespect, and trying to pretend that it doesn’t hurt because it’s too dangerous to look weak. Victims are coerced into treating the harm they suffer as a shameful secret, even when the crimes committed against them are public knowledge.

Far more people have seen misleading TV shows than have ever seriously listened to abuse victims describe their experiences. Television has led people to expect that assault victims, like drowning victims, will thrash against the waves and loudly cry for help. When a real woman smiles at a powerful man who won’t take his hand off her leg, or says, “It’s OK, really,” or even quietly and insistently says “no,” bystanders do not understand that she is in danger. Meanwhile, abuse victims are coerced into giving the impression that nothing is wrong. Those who speak up are punished more often than they are protected, with devastating consequences.

In their consistent testimony about Weinstein’s behavior, his victims describe the professional and legal pressure they faced to be peaceful and show the world that they were OK. Weinstein does not face this pressure. In multiple statements, he has expressed intense distress in terms that suggest he feels he is is entitled to sympathy and validation. He has also expressed an expectation that he will be forgiven and restored to his position if he makes enough progress in therapy. No professional association has condemned or will condemn Weinstein’s perceptions of therapy, because they are within normative practice.

Women and other marginalized people are familiar with this pattern. When accused of abusive or oppressive behavior, privileged people seem to expect that with the right combination of apparent remorse and therapy, others will comfort and forgive them. Women who complain about sexual harassment, disabled people who demand usable bathrooms and people of color who ask white people to stop using racial slurs all face this kind of emotional retaliation. Victims are pressured to disregard their own feelings in order to help perpetrators feel better about themselves.

In his statement following The New York Times expose, Weinstein briefly apologized for the “pain” caused by his behavior, but pivoted quickly to emphasize his own feelings.

“Although I’m trying to do better, I know I have a long way to go. That is my commitment,” his statement read. “My journey now will be to learn about myself and conquer my demons.”

Weinstein is pursuing therapy not for the sake of his victims, but because he is suffering and would like to feel better. In the professional literature, this sense of woundedness is called moral injury. Weinstein and others who see their own moral injury as a bigger problem than the harm they have done have no trouble finding therapists and spiritual leaders willing to validate their worldview.

Spiritual leaders and therapists are too often more willing to put pressure on victims to forgive. For both victims and perpetrators, justice is dismissed as a spiritual distraction and healing is purported to depend on deciding that the abuse doesn’t really matter anymore.

Well-meaning people rush in to tell victims that their abusers “only have as much power as you give them,” as if spiritual growth can somehow stop bullets, restore lost professional standing or render formative experiences irrelevant. Abuse has consequences that are beyond the control of victims, but it is almost never socially acceptable to acknowledge this. This is spiritually corrosive to everyone involved.

Superficially gentle lectures on the importance of tolerance, forgiveness and second chances prevent those who are being drowned from crying out for justice. This cowardice sometimes disguises itself as the virtue of tolerance, but it is just as misogynistic as sexual harassment. Both of these violent acts send the message to victims that their lives matter less than someone else’s self-image. Victims of all genders deserve solidarity from their spiritual leaders.

It is time to stop keeping secrets about the consequences of abuse.

(Rabbi Ruti Regan, @RutiRegan, is a Conservative rabbi and disabled disability advocate. She writes the realsocialskills.org blog. She provides ritual consulting and training for rabbis, cantors and communities in accessibility and disability-informed spiritual leadership. )

Help ensure Jewish news remains accessible to all. Your donation to the Jewish Telegraphic Agency powers the trusted journalism that has connected Jewish communities worldwide for more than 100 years. With your help, JTA can continue to deliver vital news and insights. Donate today.