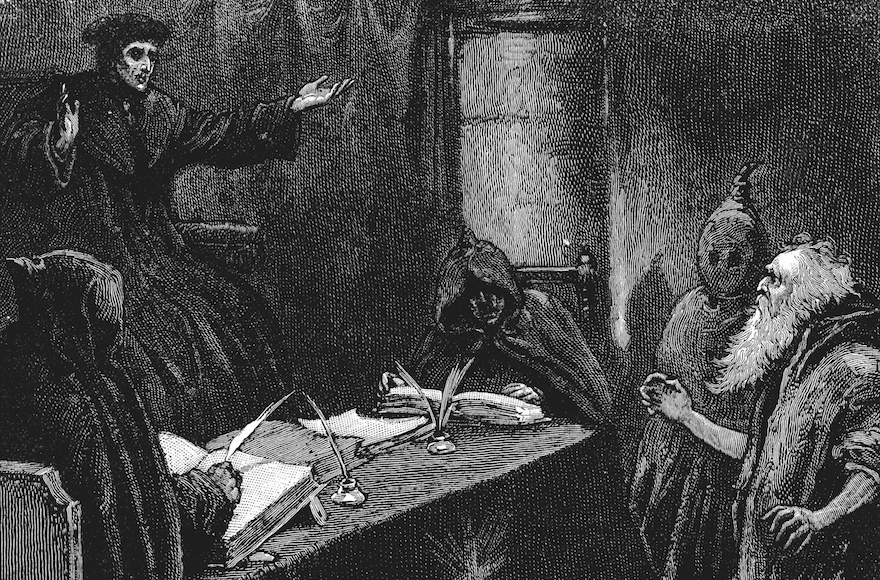

(JTA) — Here’s something no one expected: A reputable conservative magazine has published a column defending … the Spanish Inquisition.

To be clear, this is not Monty Python. This is a column in the National Review. Here’s the headline: “The Spanish Inquisition Was a Moderate Court by the Standard of Its Time.”

Moderate?

We’ll run down some basic facts about this infamous, brutal, centuries-long persecution of the Jews below. But first, let’s read some of the takes from the column by Ed Condon, who was identified as a writer, editor and practicing canon lawyer.

“[W]hile any reasonable person would find a lot not to like about the Spanish Inquisition,” writes Condon, in perhaps the understatement of the year, “[i]n fact, examined simply as a functioning court, the Spanish Inquisition was in many ways ahead of its time and a pioneer of many judicial practices we now take for granted.

“Let’s start with the basic legal concept of an ‘inquisition.’ It just means a court of inquiry in which the judges take the lead in directing proceedings in the pursuit of truth, rather than a prosecution-driven adversarial system. Such courts continue to function in many secular jurisdictions today, and there is, frankly, nothing very sinister about it, though it appears alien to those of us raised on American courtroom dramas.”

Condon goes on to claim that the Inquisition was “actually a reluctant creation of the Church.” To Condon, Tomas de Torquemada, Spain’s infamous Grand Inquisitor, was “a much more nuanced historical figure than the cartoonish portrayal of him suggests.” He calls the Inquisition’s use of torture — wait for it — “downright progressive.”

He also writes that “the jails of the Inquisition were universally known to be hygienic and well maintained.”

Astonishingly, Condon says that the Inquisition was created to protect Spanish Jews, who were forced to convert to Christianity under threat of expulsion or death.

“The pope hoped, perhaps naively, that by getting directly involved, the Church could bring the situation under control and end the frenzied religious denunciations,” Condon writes.

He acknowledges that that idea didn’t quite go as planned, but blames the Spanish monarchy for “hijacking” the Inquisition. But then, he says, Torquemada brought it under control and set up a relatively fair justice system. He writes that the Inquisition courts were fairer than Spanish civil courts.

That last point may very well be true, but … who cares?

During the Inquisition, which wasn’t abolished until the early 19th century, hundreds of thousands were forced into exile, and thousands were converted under duress. Tens of thousands more were murdered.

It was a reign of terror that persecuted people based on their religion and, significantly, their race. Even pious Catholics with Jewish roots were targeted. It struck fear into an entire population that was already forced into secrecy.

“Once the identity of the accused individuals was established, they would be seized, thrust into inquisitional dungeons, interrogated (occasionally under torture), and sentenced to a variety punishments, ranging from terms of penitential service to imprisonment or to ‘relaxation,’ that is, death,” Howard Sachar wrote in his book “Farewell Espana: The World of the Sephardim Remembered.”

“Thus, even in its earliest phase, between 1479 and 1481, in a ferocious reign of terror, nearly four hundred individuals were burned at the stake for heresy in the city of Seville alone,” Sachar continued. “Throughout Castilian Andalusia, some two thousand persons were burned alive, seventeen thousand others were ‘reconciled,’ that is, spared the death penalty but subjected to such punishments as imprisonment, confiscation of property, and debarment from all employment, public and private. Their wives and children faced destitution.”

The Inquisitors were particularly vicious in their treatment of conversos, or converts who were suspected of practicing Judaism in secret. In all, some 30,000 conversos were burned at the stake. On Mallorca, 82 conversos were condemned in 1691. Thirty-four were publicly garroted and their bodies were burned in bonfires. Another three, including a rabbi, were burned alive.

In 2011, Mallorca’s regional president offered the country’s first formal apology for the Inquisition’s killing of Jews.

Benzion Netanyahu, the late father of the Israeli prime minister and scholar of the Inquisition, did assert that King Ferdinand (that King Ferdinand) backed the Inquisition in part to prevent a wider, popular bloodbath. But Netanyahu also insisted that in its purveyors’ deadly pursuit of racial purity, the Inquisition was a precursor to the Holocaust.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.