This article originally appeared on Alma.

Ayelet Tsabari says she cannot see herself not writing something Mizrahi, or Yemeni.

“Of course, I might change my mind later,” she tells me in the midst of our conversation. “But now, whenever I think of ideas for stories and books, there’s always that component in it.”

Tsabari’s desire to tell her story — and the story of her community — has been clear throughout her career.

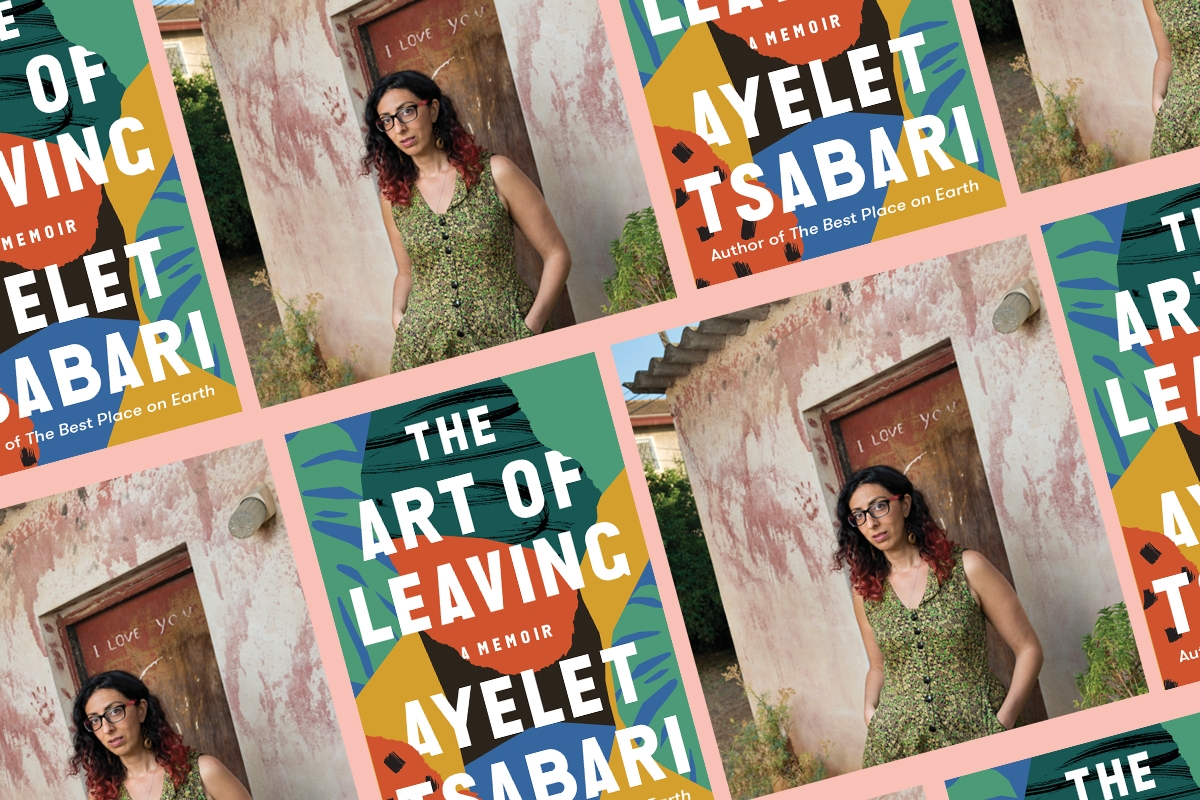

In 2016, she entered the literary scene with a collection of short stories centering on the Mizrahi Jewish experience, “The Best Place on Earth,” which won a plethora of awards. Now she’s back with the story of her own life.

Her new memoir, “The Art of Leaving,” begins with her father’s death when she was young, weaving through her childhood as a Yemeni Jew in Petach Tikvah, Israel, her service in the Israeli army, her subsequent travels in India, America and beyond, her past loves, and her large Yemeni Jewish family. It’s a story about leaving home to find yourself, which sounds cliche — Tsabari’s writing is anything but.

“Growing up,” Tsabari writes in “The Art of Leaving,” “I had often felt out of place in my own country, a feeling I couldn’t comprehend or name until much later. It had to do with my father; grief shakes the foundations of your home, unsettles and banishes you. It might have also had to do with the exclusion of my culture from so many facets of Israeli life, with not seeing myself in literature and in the media, with being taught in school a partial history about the inception of Israel that painted us as mere extras. Or perhaps that failed sense of belonging was an Israeli predicament, because how does one feel at home when home is unsafe, forever contested? When the fear of losing is so entrenched in us it has become a part of our ethos?”

I had the opportunity to speak with Tsabari about the book, Ofra Haza, her mom, the 40-plus books currently on her nightstand and why she (probably) won’t translate the memoir into Hebrew.

A large part of your memoir is about your travels away from Israel. One small passage caught my eye — how you titled your bank account during those years “The wandering Jew fund.” Did you view yourself as a wandering Jew? Or do you still see yourself as one?

There was something about it that I found romantic those years: the idea of wandering. It’s funny because I was attached to the romance of that, but I didn’t think of the tragedy of the wandering Jew, which was something that only occurred in retrospect.

Often when you’re in the midst of your 20s, or even [later] for me because I was a late bloomer, you don’t always have that much insight about what is going on and why you’re doing the thing you’re doing and the choices you’re making. That’s why writing the memoir for me was such a therapeutic … I hate saying it was therapeutic because I don’t think it’s why we should be writing. You know, I shouldn’t say that because for some people it is. But as a writer, as a professional author, I don’t think that’s why we generally write. But it is an element of [writing].

Memoir is so crazy. It’s such an intense immersive experience. If I would’ve done it again, I probably would’ve done it with the support of a therapist. I think that would’ve been wise. I mean, I survived, but …

You have the book now!

I do, I do. And there is a sense of closure, in a way. Now that I’m done, there is some sort of relief for sure.

You write about the stories of your assaults in the book — by your friend’s dad, and on the bus in Vancouver. What was that experience like, putting them down on paper?

It took me a while to actually be able to write it. I often tell students that I understand the need to write something right after it happens, but if you’re trying to craft it into an actual piece of art, a memoir or a creative nonfiction, I always say it’s best to wait. [You should] write notes, have as many notes as you can, but it’s probably not going to shape itself into a story, a narrative, or a piece of art until some time has passed and you have a little bit more distance.

And that was definitely true for both of these pieces. I needed the distance to be able to be just enough detached from it so I could not fall apart. And I would say that about a lot of things in the book; I would say that about my father’s death. You need some distance to really make sense of it, I think, in writing.

Did it change your perspective, or give you that sense of closure you felt like you needed?

I’m really glad I told the story about my friend’s father because it was such such an unopened box in my body for a long time, and I think a lot of women who have experienced sexual assault have the same story. It’s like an ulcer in our bodies. There is something positive about the experience of letting it out and telling the story.

On a sort of different note — and I apologize for my pronunciation ahead of this question – you write about Ofra Haza. I can’t pronounce her name, I’m so sorry.

No! You did a good job. That was good.

As an American Jew, I only knew her as the voice in “The Prince of Egypt.”

Yeah! [Laughs]

And I went down a total deep dive after I finished reading your book …

Oh my god!

Into her Wikipedia and YouTube videos and all that. So one, just thank you for introducing me to her.

Oh my God, I am so glad to hear that. Seriously, I really am.

Can you talk a little more about what Ofra Haza’s visibility as a Yemeni Jew meant to you growing up? And her impact on you?

She was everything as a young child. You know? Seeing a woman like her succeeding in such a way, then being in the Eurovision contest — she won second place in the Eurovision — she was one of very few role models for me, and for young girls like me.

And there was something really special about her, and I’m saying that without cynicism: She was special.

She really did give me hope, you know? Because there weren’t many [Yemeni Jewish] artists, and definitely no writers, but [Ofra Haza was] someone who made it. And made it so big, and was humble and beautiful and dark-skinned and Yemeni. She was definitely the darling of the community. It was a huge loss, her death, at such a young age.

I loved the Ofra bit, just because it really introduced me to her, but my absolute favorite part of your memoir was when you write about your relationship with your mom through the food that she makes. What has her reaction been like to your book?

So my mom does not read English, and the book, so far, has not been translated into Hebrew, and I’m not sure if I will do that or not. I’m a bit hesitant. But I have a written a summary of the parts in which she’s mentioned in Hebrew, and I sent it to her so she knows what is being told and what I have written about her. Obviously it’s not the same as reading the entire book. She was OK, she was supportive. I cannot say I’m not still nervous.

I remember talking to Sean, my partner, about it, even before, when it was just “Yemeni Soup and Other Recipes” published in a tiny little magazine, and I was worried then. And he said, “Why are you worried? It’s such a loving piece.” It may be loving, but it’s still really honest and talks about a lot of painful stuff that I don’t know if she wants to be reminded of. So I am nervous.

What about the rest of your family?

With my siblings, they kind of just said, “Do whatever you want.” My brothers are fairly easy-going. I’m like, do you wanna read it? See what I wrote? And they’re like, yeah, whatever, we trust you.

My sister, who also just read the parts that were about her, was really moved by it. That’s easy because I’m writing really fondly of her, so of course she’d love it.

But none of them have actually read the entire book yet. I am nervous, I’m nervous about the whole thing. It’s huge exposure. A part of me wonders, why on earth would anyone choose to do this? [Laughs.] But then on the other hand, I know that there was a deep need, on my part, to do it. It was such an urge, it wasn’t really calculated, it was what had to be written. I just followed that. I just listened to that.

You mentioned you don’t know if you want to translate this into Hebrew —

Yeah.

Can you explain a little more on why you wouldn’t want to translate it, and if you ever hope to write in Hebrew in the future, what that would look like?

When I first started publishing in English, people in Israel didn’t really know about me. And then the book came out in Israel, and I belong a little bit now in the literary community in Israel. I mean I’m a little bit of an outsider because I am writing in a different language. But I have been asked a couple times to write stuff in Hebrew, and I’m glad to do it.

That said, I feel like at this point, I’m going to stick to English. For many, many reasons. My career is in English, and I think it would be a mistake, career-wise, to write in a language that has a much smaller readership, despite the fact that obviously I have love in my heart for the Hebrew language that’s never gonna stop. But for now… it’s not like I’m making that decision as a business decision, you know. It’s not like there’s a dissonance between my heart and my brain right now. I’m still very much into writing in English, and I love the challenge of it, the newness.

And with regard to publishing “The Art of Leaving” in Hebrew?

Israel is a very small place, as you know, there’s something that can feel very familial about it, which is both positive and not so positive at different times and different instances. And I’m a little bit nervous.

The exposure, despite the fact that it’s a smaller readership as I just said, somehow feels more. Just more. More on point, more scary, and there’s mom … I know it’s silly, and I know I’m not a child, and still I’m a little bit nervous. So I’m not sure. I haven’t decided yet, I am talking to people who are trying to convince me.

I don’t know if you know the story of Etgar Keret’s memoir?

No, I don’t.

He did not publish [his memoir] in Israel either. Etgar Keret is a very famous Israeli writer, very successful in the world. He writes in Hebrew, lives in Israel, so he wrote his memoir in Hebrew, had it translated into English and into many other languages, and did not publish it in the original language in which it was written, for similar reasons. So, yeah, I’m not even the first to do this, funnily enough. But we’ll see.

Do you think there’s been increased awareness of Mizrahi Jewish culture in English-language speaking communities?

I sure hope so. I do my part. It’s a small part. But every time I get to speak in front of people, I correct misconceptions, which happens often. People saying things like “Mizrahi Jews didn’t come to Israel until the founding of the country, so that’s maybe why …” And I’m like, “Actually, my great-grandmother came in 1907, and the first Yemeni immigration was at the same time as the Bilu immigration of the European Jews, exactly the same years, it just hasn’t been told.” So yeah, you have to do what you have to do.

When I was working at a Lebanese restaurant [in Canada], I was doing a small part in the fight for world peace: by being there, working with other Middle Eastern people, and introducing people to my culture and making them like me [laughs].

I do what I can. And I hope that it’s helping in making some impact.

Being in that Lebanese restaurant, and speaking about your books, does it ever feel like a burden?

No, no, I actually quite like it. I’m one of those — I know a lot of authors are introverted. I like people. I like being out in the world because I like meeting people, I like hearing people’s stories, I like talking to strangers. And I find that especially because as a writer I spend so much time holed in my little room — in my imaginary world — I need that balance. And giving talks and teaching both satisfy my need for social interactions and my love of community. They’re my attempt to give back in some small way.

Does the build-up to the release of this book feel different than “The Best Place on Earth”?

Yes and no. There’s nothing quite like your first book. It’s such an unexpected thing, even though you dream about it your whole life, you plan for it, and still, when it actually happens, it’s such a shock that it’s actually happening.

And not so much the build-up, but the experience of writing is very different. When you write your first book, you get to write it in a bit of a bubble. You don’t know if it will be published, as much as you hope and wish for it, you don’t really know that. It’s kind of a safer place to write. And then when you write the second book, you’re aware of readership, you’re aware of views, of an audience out there, of expectations, and it’s more work to shut that down.

Or shut it up, you find the right preposition! I’m ESL, help me out.

Both work! Who are the Jewish writers writing today you think everyone should be reading?

The interesting thing, of course, is a lot of the Jewish writers I read are Israeli writers who write in Hebrew, and some of them have not been translated, so there’s that.

I particularly enjoy young Israeli poets, many of them Mizrahi, like Yonit Naaman, Adi Keissar, Maya Tevet Dayan and Shlomi Hatuka.

Apart from that, I’ve just finished Nathan Englander’s next book [kaddish.com], and I love his book of short stories. I like Dorit Rabinyan’s book that was published in English as “All the Rivers.” Idra Novey, I love her, she’s wonderful. And Sigal Samuel is another [writer] I really admire.

And my last question for you: In your memoir, you write about how you always travel with books because it makes you feel at home wherever you are, and I loved that so much. What are you traveling with now? What’s on your nightstand?

Oh my goodness, there are so many books, it’s kind of out of control. So the thing is, I’m now judging a Canadian contest and I have to read about 40 books of short stories, and I’m only on my second. So there’s that. Apart from that, again, a pile of Hebrew books, I can’t really — there’s too many to mention.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed.

“The Art of Leaving” comes out Feb. 19.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.