(JTA) — The Passover seder can be boring for kids. A new Haggadah is trying to change that.

Published by Kveller, a Jewish parenting site, the Kveller Haggadah is “for curious kids — and their grown-ups.” The Haggadah’s co-creators are Elissa Strauss, a columnist on parenthood for CNN, and Gabrielle Birkner, the co-author of “Modern Loss: Candid Conversation About Grief. Beginners Welcome” (Harper Wave, 2018) and a former managing editor of JTA.

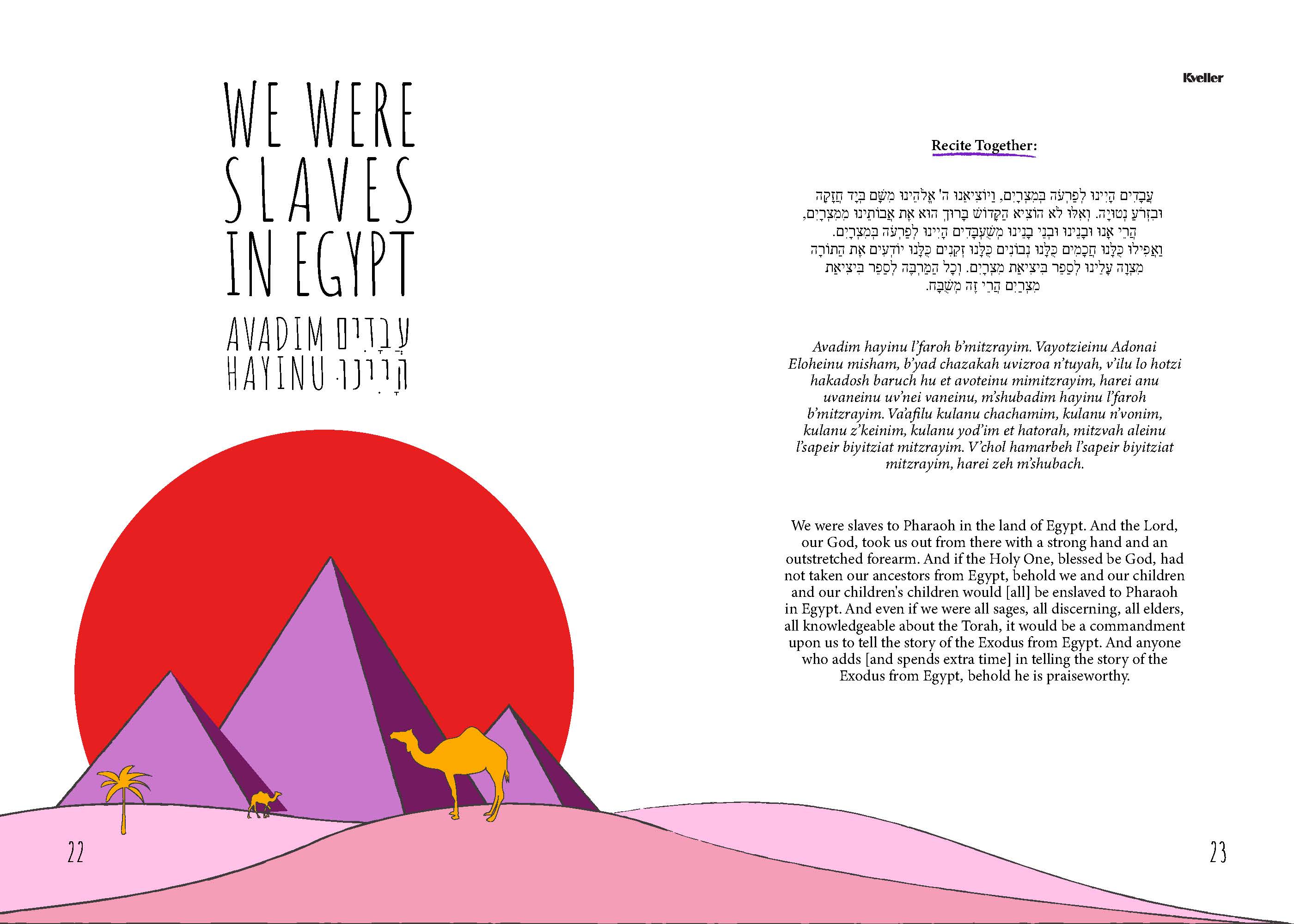

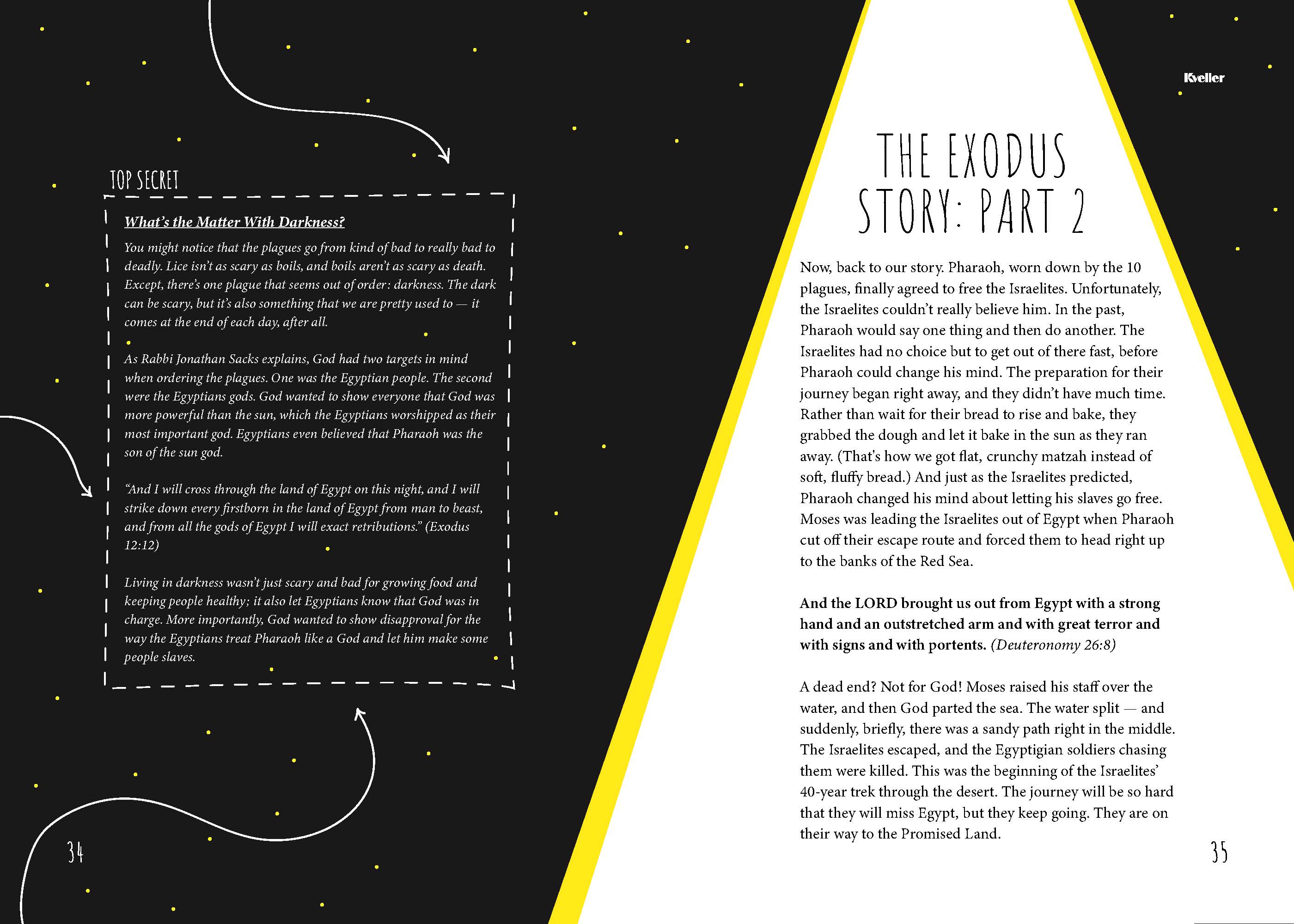

Strauss and Birkner don’t skate around the darker parts of the Passover story; they approach them head-on. And it obviously includes the classics. The Haggadah also has beautiful illustrations on every page by 70 Faces Media’s multimedia editor, Hane Grace Yagel, making the centuries-old text engaging and fresh.

“Every year, people ask Kveller, ‘which Haggadah should we use this Passover?'” Kveller editor Lisa Keys said. “And we never had a good answer for that.” Until now.

“This is not a ‘Haggadah for kids,'” Keys said. “It’s a highly accessible, dynamic Haggadah that engages children and grown-ups.”

(Kveller is published by the Jewish Telegraphic Agency’s parent company, 70 Faces Media.)

JTA spoke with Birkner and Strauss about their creative process behind the Haggadah, their own Passover seder experiences and what they hope families take away from the Kveller Haggadah.

JTA: The two of you “created this Haggadah to be informative and spiritual, and even a tiny bit weird.” Can you talk what inspirations you drew from?

Strauss: We were inspired by a mix of the very new and very old. We thought a lot about the latest and most popular narrative forms for kids, things like podcasts and video games, and tried to figure out what kids like about them. Video games often contain narratives that are very high-stakes, and children love that. They want to feel like the world they are immersed in is exciting, and what is happening matters. Well, the same can be said of ancient Jewish texts. They are intense, high-stakes and operate under the assumption that if the story is good, children will pay attention. Also, children tend to be highly preoccupied with ethics, just like the rabbis of yore. They don’t just want to know what to do, they want to know why they should do it, too.

The Kveller Haggadah was designed by Hane Grace Yagel, 70 Faces Media’s multimedia editor. (Kveller)

Birkner: It would be cliché to say my kids inspired me. It would also be true. This Haggadah treats children like the curious, creative and capable humans we know them to be — little people who are drawn to epic stories, who believe in things they can’t see, and who always want to know why, why, why. This text stokes and rewards their curiosity. In the case of the Kveller Haggadah, Elissa and I brought our identity as parents of young (and curious) children. We sought to create a Haggadah that is substantive and spiritual, made for kids but engaging for all.

What was the most challenging part to write?

Strauss: The part about asking God to smite our enemies is top of the list for me. We included it because the Haggadah isn’t just about learning lessons from the past; it’s about feeling as though we lived through it. Instead of ignoring the rage, we want to acknowledge it, and then consider it. Anger is a common response to injustice. What should we do with it?

Birkner: It was challenging to think through how to incorporate Moses into our text. Traditional Haggadot don’t really mention him. The focus is on God’s “outstretched arm,” not the hands of a mere mortal — no matter how remarkable. (By contrast, some contemporary Haggadot highlight Moses’ role and downplay God’s role.) In the Kveller Haggadah, God is at the center of the seder rituals and the focus of our gratitude. But Moses’ life and leadership are explored in the Exodus story (another thing that is omitted from traditional Haggadot, but not ours), and in some of our supplementary content, such as Rabbi Ruti Regan’s reflections on Moses’ disability.

Did you learn anything new about Passover (and the seder) while working on the Haggadah?

Birkner: So much. There’s something on almost every page that I didn’t know when we started out, from why we wash our hands twice before the Passover meal (even if they’re clean) to why we say “Next year in Jerusalem” (even if we have no plans to be there). I learned what Passover looked like in the Temple era (a whole lot different) and why we eat the afikomen for dessert (even though it’s not the least bit sweet). I also learned about what’s traditionally left out of Haggadot — Moses and the Exodus story, as I mentioned earlier — but also the answers to the Four Questions.

The Kveller Haggadah approaches the darker parts of Passover head-on. (Kveller)

What is your favorite part of the seder to do with your kids?

Strauss: Elijah’s cup. It’s such a deeply mystical concept, and we are not a deeply mystical family. But when we pour that glass, and chant his name, we turn into just the kind of people who believe the spirit of an ancient prophet may actually enter our home. I love how the Haggadah takes us there, making us ripe for miracles, if only for a few minutes.

Birkner: I love saying the Shecheyanu blessing with them on the first night. Kids live in the moment, and the Schecheyanu thanks God for this … very … moment. It’s essentially a mindfulness prayer. This year, I think they’ll be fascinated to learn how memory (the theme of this Haggadah) works — and about why it’s their job to be the keepers of memories.

What do you remember from your seders growing up?

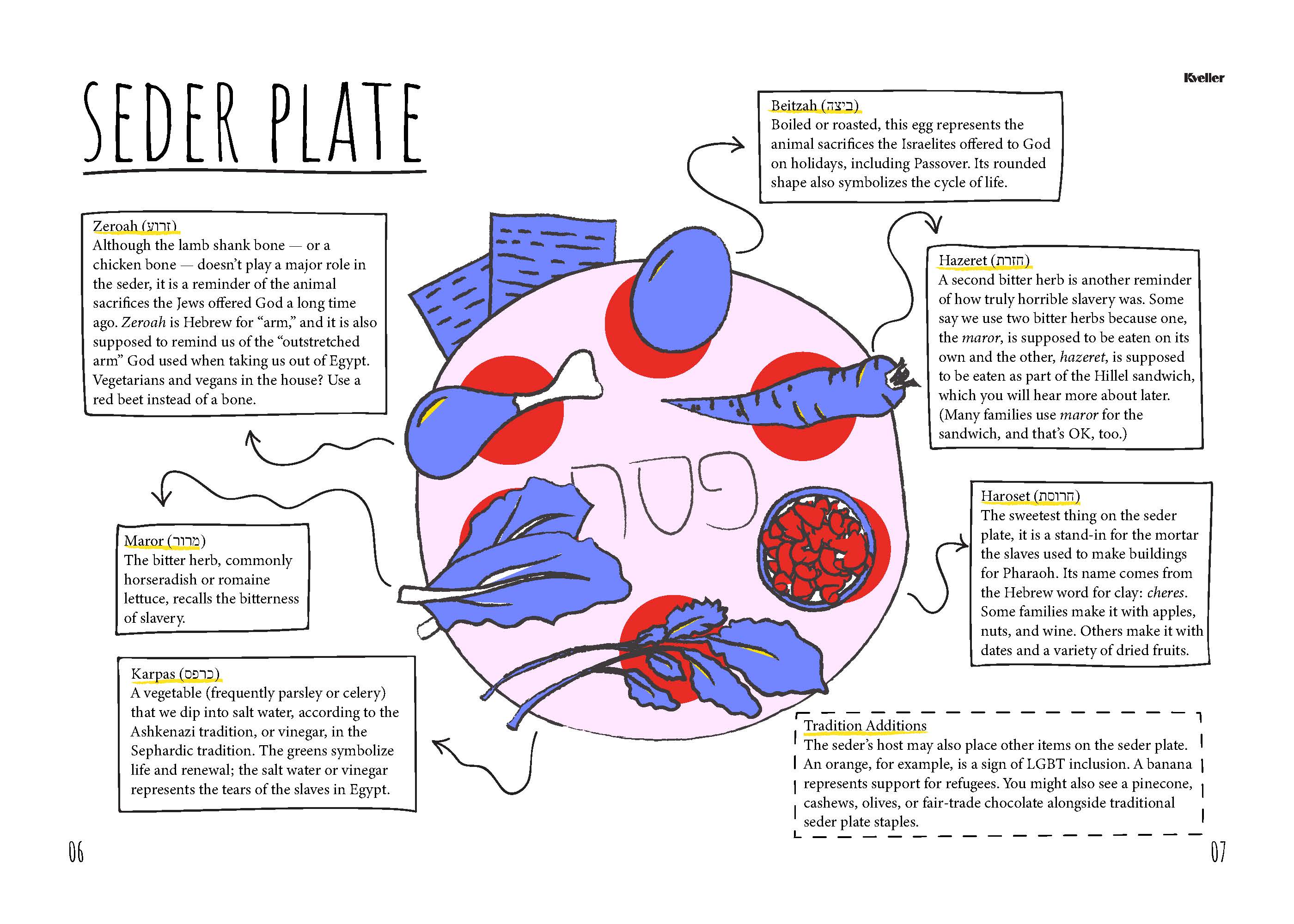

Strauss: The food, which is by design, of course. The matzah, the charoset, the maror, the parsley dipped in the saltwater which somehow tastes rich and exotic in the context of the seder. Then the egg, representing both the hope of getting to eat dinner, and the hope of renewal, for all of us. It’s food poetry.

The Kveller Haggadah includes a “map” to the traditional seder plate. (Kveller/Hane Grace Yagel)

Birkner: Growing up — and to this day — my mother gets super-creative with her Passover seders, which seem to get bigger and more elaborate each year, stretching beyond the dining room and into the living room. She’ll make two kinds of brisket and three kinds of charoset. She’ll create a “Passover Jeopardy!” table game, and she’ll print out songs about the 10 plagues and insist we sing them to the tune of “Oh My Darling, Clementine,” or something. And let’s just say I’m not the first woman in my family to make her own Haggadah.

Do you have any special Passover traditions you passed along in your family?

Strauss: We are strictly anti-Cuisinart when it comes to charoset. That and the idea that if kids are in the room, the seder should speak to them.

Birkner: My mom takes seriously the idea of welcoming the stranger. Throughout my 20s, I would often call her on the day of the seder and let her know so-and-so and so-and-so’s cousin don’t have anywhere to celebrate the holiday and would be coming with me. She’d add two more place settings, no questions asked. In addition, our family seders almost always include one or more guests experiencing a Passover seder for the first time — including, some years, clergy from other faith traditions.

What do you hope families take away from the Haggadah?

Strauss: My big gripe with a lot of contemporary expressions of Judaism is that they push us to choose between accessibility and substance. This is a false choice. One shouldn’t have to attend a yeshiva or be Orthodox to gain access to a complicated, engaging and fleshy Judaism. It should be made available to all. I hope families who use our Haggadah gain an appreciation for the depth and richness of our tradition, and that it makes them hungry for more.

You can download the Kveller Haggadah at kveller.com/haggadah.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.