NEW YORK (JTA) — In the bullfighting world of the 1920s and ’30s, Sidney Franklin was defined not only by his Americanness, elegance or tough-guy personality but also by his Jewishness. The first American to reach the status of a matador in Spain, he was nicknamed “El Torero de la Torah,” or “the Torah bullfighter.”

But Franklin had a complicated relationship with his Jewish identity. Born Sidney Frumkin in an Orthodox Jewish family in Brooklyn’s Park Slope neighborhood, the matador-to-be often clashed with his traditional father. The fact that he was gay (although not openly so) made him feel even more alienated from his religion.

On Monday, the Center for Jewish History here is hosting a lecture about Franklin. Set during June, which is Pride month, the talk will explore both his Jewish and gay identities.

“He was filled with contradictions,” said Rachel Miller, director of archive and library services at the Manhattan-based center. “It’s fun to look at him today when we have a very different perspective now than we did 100 years ago on gender and queer identity, Jewish identity also, and the effects of trauma.”

Miller has been researching Franklin’s life since 2010. She stumbled upon his story while sorting through materials about him held by the center and was intrigued upon learning about his family background. His parents fled anti-Semitism in Russia to settle in New York, where his siblings remained.

“Then what’s with this one who goes off to Mexico City and Spain and everywhere else as a bullfighter?” Miller wondered.

From a young age, Franklin clashed with his father, a burly police officer who would physically discipline his children.

“Sidney rebelled against basically anything that his father in particular stood for, and they had a very difficult relationship,” Miller said. “By today’s terms we would call his father abusive.”

At the age of 18, Franklin left Brooklyn for Mexico. It was there that he discovered his love for bullfighting, learning from the prominent torero Rodolfo Gaona. He seemed unfazed by the dangers of the bloody sport.

“If you’ve got guts,” Franklin once said, “you can do anything.”

Moving to Spain to pursue his passion, he rose to fame in part because of his bullfighting skills and the circles he frequented.

In 1929, Franklin met Ernest Hemingway. The celebrated author became a close friend and wrote about Franklin in his book “Death of the Afternoon,” which explores the bullfighting tradition.

“Franklin is brave with a cold, serene and intelligent valor but instead of being awkward and ignorant he is one of the most skillful, graceful and slow manipulators of a cape fighting today,” Hemingway wrote. “His repertoire with the cape is enormous but he does not attempt by a varied repertoire to escape from the performance of the veronica as the base of his cape work and his veronicas are classical, very emotional, and beautifully timed and executed. You will find no Spaniard who ever saw him fight who will deny his artistry and excellence with the cape.”

In 1932, Franklin played himself in the Hollywood film “The Kid From Spain” alongside Eddie Cantor.

Though the bullfighter was Jewish, he would participate in some Catholic rituals ahead of his fights, including having nuns pray for him, his niece, DorisAnn Markowitz told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

“When someone asked him why he allows nuns to pray over him if in fact he’s Jewish, he said because the bulls are Catholic,” she recalled. “That was just a joke. He did not take religion per se seriously.”

But as evidenced by his nickname, his Jewish identity still played a big part in his life, at least in terms of how others viewed him.

Another lesser-known aspect of his identity was his sexuality. Franklin was gay but never spoke publicly of his sexuality, though Miller said it was “an open secret” in the bullfighting world.

Markowitz said the family knew about his sexuality but never spoke about it. When visiting his family, she said, Franklin would bring along a valet named Julio, who was also his romantic partner.

“Julio — Julie we used to call him — lived with us in our house, in our basement with my uncle, and it was very easy to see the special relationship that the two of them had together,” Markowitz said.

Still, Franklin made attempts to hide his sexuality, including making up a relationship with a woman and other heterosexual escapades in his unreliable 1952 autobiography, “Bullfighter from Brooklyn.”

Miller said that being part of the macho bullfighting world allowed Franklin to escape some speculation about his sexuality. But that world also allowed him to express it in other ways.

“[Franklin] blew up this macho image of himself, which I also felt was an act of closeting, but at the same time an act of performance,” Miller said.

Accounts of him being photographed for the first time wearing a bullfighting costume — the practical and flamboyant “suit of lights” that includes skintight pants and a short, padded jacket with intricate brocade — show how much he enjoyed the sport’s glamour.

“He was looking at himself in the mirror, and hours passed and he couldn’t get enough of himself and how he looked in this shimmering golden and silver suit,” Miller said.

As his bullfighting career wound down, Franklin managed a cafe in Seville. In 1957, he was jailed for illegally keeping a car in the country, serving nine months of a 25-month sentence. Following his release, he returned to North America, where he went back and forth between Texas and Mexico. He died in 1976, spending the last years of his life in a nursing home.

Looking back at her uncle’s life, Markowitz remembers him as “a larger-than-life figure.”

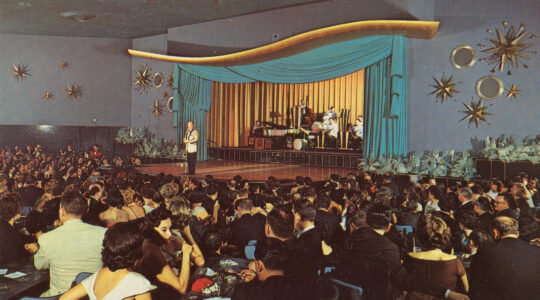

“When he came into a room, he lit it up,” she said, “and when he came into that room he was, no doubt about it, the focus of everyone’s attention.”