WASHINGTON (JTA) — Allan Gerson, a lawyer who made it easier for the families of terror victims to sue foreign governments, has died.

His daughter Daniela told family and friends that he passed away Sunday at his Washington, D.C., home. His wife, Joan Nathan, the cookbook author and authority on Jewish cuisine, told The Washington Post that Gerson, who was 74, died from complications from the degenerative brain disease Creutzfeldt-Jakob.

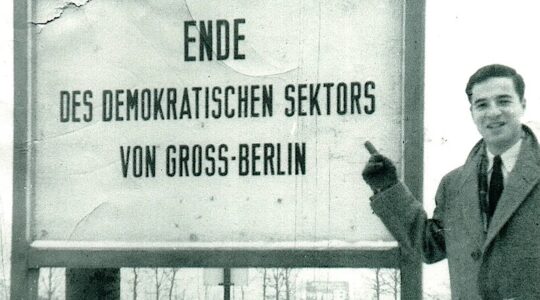

In 1992, by his mid-40s, Gerson had already made a name for himself as a member of the U.S. Department of Justice team that helped bring to justice Nazi war criminals, a Reagan administration deputy assistant attorney general whose focus was human rights and a senior counsel to U.S. ambassadors to the United Nations.

Gerson then launched the process that would lead him to the unprecedented challenge of suing Libya for its government’s role in the 1988 bombing of a Pan Am airliner over Lockerbie, Scotland.

The bomb killed 259 people on board and 11 on the ground. The efforts of Gerson and his team were frustrated at first by the principle of sovereign immunity, which maintains that foreign governments are above the law. Separate lawsuits targeting Pan Am for poor security measures seemed to be the more sensible route for redress for victims’ families.

Rebuffed by the courts, Gerson took his case to Congress, which eventually passed laws that were upheld by the courts and have led to a new discipline of law that holds foreign entities accountable for terrorist attacks on U.S. civilians. Under the laws, attorneys have successfully sued Iran and the Palestine Liberation Organization, among others. Gerson’s efforts led to $10 million payouts by the Libyan government to each Lockerbie victim starting in the early 2000s.

A separate lawsuit Gerson joined against Saudi Arabia for its alleged role in the 9/11 attacks is still in the courts.

Gerson, a native of the former Soviet Union, moved with his Polish-born parents to the United States in 1950 under false identities, assuming the names of a family that had permission to enter the country. They eventually obtained legal status and citizenship under their real names.

That led Gerson to identify in a 2017 op-ed for The Washington Post with “dreamers,” undocumented immigrants who had arrived as children.

“Deportation is terribly punitive, especially for the young who have known no home other than the United States and did nothing worse than hold on to their parents’ hands,” he wrote. “And even if not deported, today’s dreamers could still face severe deprivation, including limits on their ability to work and to obtain funding for college.”

Gerson, who dabbled successfully in photography and jewelry design, is survived by three children, two grandchildren and a brother, in addition to his wife.

His family asked that he be honored with contributions to HIAS, the Jewish immigration advocacy group that assisted in his settlement and that now advocates for dreamers.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.