(JTA) — Shahak Shapira was 14 when he moved with his mother and brother from Petach Tikvah in Israel to Laucha, a small town in Germany.

That was where his mother’s boyfriend Olaf lived — along with a significant local population of white nationalists. Today, about 13% of the town’s residents vote for NPD, a far-right, ultranationalist party.

Shapira just knew that he wasn’t readily accepted.

“I passed for German until they learned my name,” he said of the people there. “Then I became the town’s Jew. You don’t want to be the town’s Jew.”

Nearly two decades later, Shapira is not just Laucha’s Jew — he is one of the most prominent Israelis in Germany. Through stand-up comedy and a late-night TV show, the 31-year-old has lampooned the country’s rising far right and the German people’s relationship to the Holocaust alongside more lighthearted topics such as Israelis’ love for hummus.

But after his show was canceled for what the comedian suspects were political reasons, Shapira — a grandson of one of the Israeli athletes murdered at the 1972 Munich Olympics — is contemplating moving on.

“I’m not sure I see a future for myself in Germany,” Shapira told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency. “I don’t feel at home here, not anymore.”

Shapira burst into Germany’s consciousness on New Year’s Eve 2015, when several Arab men beat him on a Berlin metro train because he had objected to their singing anti-Israel and anti-Semitic chants. The incident received prominent coverage in Germany, where it was a harbinger of the current rise in anti-Semitic attacks there.

“I grew up in a village full of Nazis and their grandchildren,” Shapira said. “I’m used to speaking out when things rub me the wrong way — and to getting beat up over it.”

Shapira worked the attack into his stand-up routines, performing in bookstores after publishing an autobiography in 2016 titled “How I Became the Most German Jew in the World.”

At a time when the outside world presented its challenges to the newcomer, Shapira’s domestic situation in Germany wasn’t problem-free either. His mother, a former gymnast and coach who retired due to health problems, would fight often with her boyfriend, and left him with her two sons several times to go back to Israel, though the couple would always make up eventually.

Despite his struggle with the German language and status as a Jewish outsider in the small town, Shapira preferred it over a return to Israel, he wrote in the book.

“As much as I hated Laucha, I saw my future in Germany,” he said. “Despite all the fights, the neo-Nazis, grammatical exceptions, I and my mother had never felt so happy and relaxed before.”

Shapira began working as a graphic designer at a small studio in Berlin, and that gave him the tools to carry out one of the projects that made him famous in Germany and beyond: Yolocaust, a website he launched in 2017 that shames people who take happy selfies at Holocaust memorial sites. The Yolocaust site put their smiling profiles against the background of actual, and sometimes gruesome, photographic scenes from the genocide.

He then infiltrated several far-right groups on Facebook, rose in their ranks, achieved administrator status and hijacked their names, changing the name of the group “The Truth about the Antifa” to “I <3 Antifa”; “Love your Homeland” to “Love your Hummus”; and “Sharia — more and more in Germany?” into “Shakira — when is she coming back to Germany?”

Also in 2017, Shapira and some of his friends spray-painted around the entrance to Twitter’s Hamburg headquarters dozens of hateful tweets that had been reported to Twitter but were not taken down.

“I figured, if Twitter makes me see these things, I’ll make them also see it,” he explained.

Those provocative acts propelled his career, and last year he landed a coveted slot on the ZDF public broadcasting channel for his first talk show.

Shapira’s family history had given him complicated feelings about the German media.

“German news crews aired live the storming of SWAT police into the Olympic compound [in 1972]. The terrorists turned on the television to see what’s going on and when to kill my granddad and the other hostages,” he said. “It tells you something about a country’s media. Maybe even about the country.”

Still, he embraced the new job, creating a mixture of roasts, stand-up routines and “Saturday Night Live”-style political sketches for two seasons. The show had solid ratings, with about 300,000 viewers tuning in weekly.

Much of Shapira’s comedy is lighthearted, making fun of Israelis (he directed a rap video called “Hummusexual”) and the trials of having a doting but technologically illiterate Jewish mother (he recorded himself patiently instructing her on how to use Netflix).

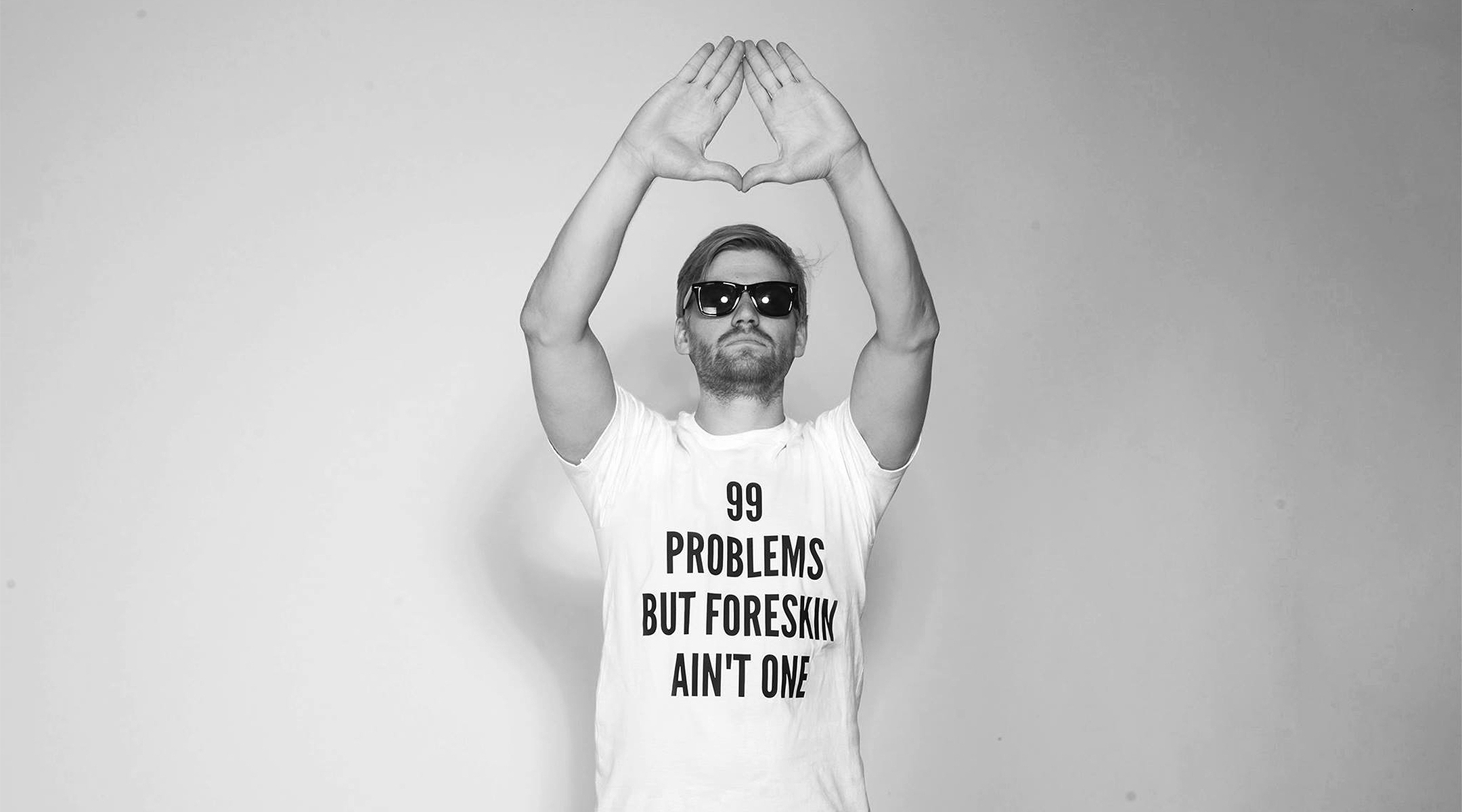

After years of trolling the far right and Holocaust tourists, Shapira no longer feels at home in Germany. (Courtesy of Shapira)

But he also constantly reminds German viewers about their country’s history when it comes to Jews like him.

“Did you know you can now rate a concentration camp on Yelp? You can choose how many yellow stars you want to give it,” he said on one show. “I learned this when I had a show in Leipzig and wanted to take a train to Buchenwald. Ironically there’s no train to Buchenwald these days. For some reason, I assumed there would be.”

In another sketch, he responds to learning that Germany supplied Israel with gas masks for protection during the Gulf War.

“I’m sorry, but we Jews needed those masks earlier,” he said. “1991 is just way too late.”

Then, in October, a different personality at the ZDF network invited Jorg Meuthen, a far-right politician for the Alternative for Germany party, or AfD, for an interview about the attack on a synagogue in Halle. Founded in 2013 as a conservative, Euro-skeptic party opposed to the euro currency, the AfD has vociferously opposed immigration from Muslim countries and is accused by its critics of encouraging racism and anti-Semitism. The party denies the assertion.

Some in the country expressed outrage, saying the network had afforded a platform to Meuthen that legitimizes his party. Shapira saw an opportunity for humor.

“The interview with Meuthen was a joke,” Shapira said. “So I told that joke.“

In a sketch from Oct. 14, Shapira portrayed a self-important journalist called Sandro Lanzberger — a reference to ZDF’s own star journalist Markus Lanz — who interviews racists as experts on the excesses of political correctness. His subjects included a skinhead and a Ku Klux Klansman called Whitey McWhite.

The routine ends with the panel giving viewers the Hitler salute — a display that is illegal in many contexts in Germany.

ZDF had skirted those laws before. In 2016, prosecutors in Berlin said they would not prosecute the network for featuring on its Facebook page a swastika-shaped schnitzel that was meant to be a commentary on the far-right’s success in elections that year in Austria. The law, which prohibits displaying “symbols of anti-constitutional organizations,” includes exemptions for when the context is satire, art or protests.

Shapira said things changed for him at ZDF after he used the salute to mock the channel. Where he once had autonomy to deliver jokes as he saw fit, he said the network began exercising more scrutiny of his work, conditioning new sketches on the consent of a special editor appointed by network executives.

Then, last month, the channel canceled the show.

Network officials said the decision had to do with Shapira’s ratings.

The show “did not meet the expectations,” Cordelia Gramm, a ZDF spokeswoman, told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency in an email. “Unfortunately the target group’s acceptance did not develop as hoped in linear television as well as online.”

Gramm declined to address whether Shapira’s display posed legal issues for the network and did not confirm whether Shapira had faced extra oversight following the Oct. 14 sketch.

Shapira said the network’s explanation did not ring true to him.

“They said they pulled the plug on the program because of ratings,” he said. “But the ratings were good, better than expected.”

Whatever caused him to go off the air, Shapira is considering his next move. He’s working on a new solo act, and will perform in English on March 18 and March 24 at New York’s Gotham Comedy Club in what will be his first major tour abroad.

He says he would be interested in moving to the United States “for professional reasons as a comedian if nothing else.” But Shapira also is among the increasing number of German Jews questioning whether they should stay put with the rise of far-right white nationalist groups.

Asked if Berlin is safe for Jews and Israelis, he responded, “I would have said so seven years ago. Now I’m not sure. But then again I’m not sure anywhere is safe for them.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.