(JTA) — In the wake of the mob that stormed the Capitol Wednesday, leaving five dead, tens of thousands of people retweeted an image meant to capture the depravity of the marauders and the insurrection they led.

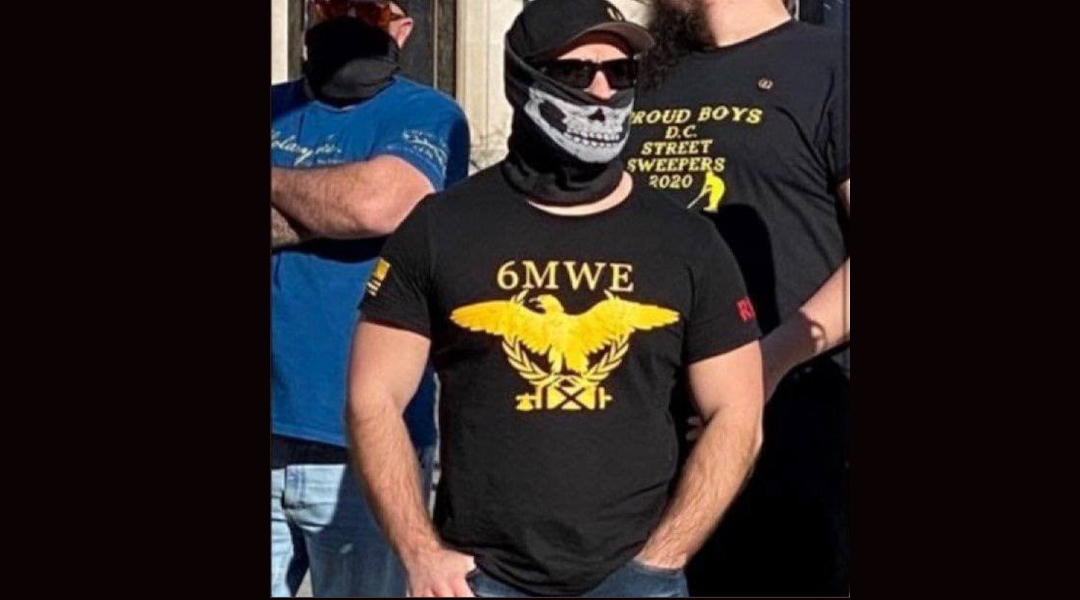

The picture showed a man in sunglasses and a gaiter, wearing a shirt with the message “6MWE,” which stands for “Six Million Weren’t Enough” and signifies that he wants more Jews to die than did in the Holocaust. It was one of many images of hate signs that people shared while attempting to document the mob, along with the now infamous “Camp Auschwitz” sweatshirt.

The 6MWE shirt swiftly drew condemnation. President-elect Joe Biden referenced the shirt on Friday when he called the mob “a bunch of thugs, insurrectionists, white supremacists, anti-Semites.” Mary Trump, the president’s niece, tweeted on Saturday condemning those “who wore 6MWE” shirts. On Monday afternoon, almost five days after the violence, New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy included a photo of the shirt in a tweet advising readers to “Take a deeper look at the crowd which overran the Capitol.”

Each got one thing wrong: The picture wasn’t from that day.

The photo was actually taken last year in Washington, D.C., according to the Anti-Defamation League, and likely depicts a member of the violent, far-right Proud Boys, a group that also took part in Wednesday’s mob. It began circulating online in December, when it may have been taken. It features the Proud Boys’ black-and-yellow color scheme, and the man stands next to a person with a Proud Boys shirt.

That information began circulating online, too, but as is so often the case, the fact-checks traveled less quickly than the posts about the shirt, which remained online. One tweet from Thursday that focused on the shirt was shared more than 20,000 times and is still up as of Monday evening. A search for “6MWE” on Twitter shows dozens of results from just the past few hours, mostly focused on the Capitol violence.

Even after the Jewish Telegraphic Agency removed a photo of the shirt from an article listing the hate symbols at the rally and added a correction, several people sent the picture or referenced it in emails asking JTA reporters to investigate.

The saga has left people who shared the “6MWE” photo conflicted. On the one hand, they say accuracy is important when documenting Wednesday’s insurrection, and they worry that sharing false news could provide extremists with an opening to discredit criticism of the mob.

But they also say that, regardless of when it was taken, the photo does show the danger of the groups that fomented Wednesday’s violence, as it likely depicts an extremist group that was present on Wednesday.

“I would certainly have taken it out. It’s not crucial to my story,” said Jonathan Sarna, a Jewish history professor at Brandeis who referenced the shirt in an essay about the insurrection and anti-Semitic ideas. “What I wanted to show was the underlying ideology of the ‘white genocide’ movement [an anti-Semitic conspiracy theory], and those who promote the ‘Turner Diaries,'” a white supremacist book popular with extremists.

According to an advanced search of Twitter, the first references to “6MWE” in relation to Wednesday’s unrest appear to have been posted that day around noon. At 10:15 that morning, unconnected to the crowds gathering near the Capitol, Snopes, the fact-checking site, had posted the photo to its 285,000 followers along with a fact-check confirming that it was anti-Semitic. Over the next few hours, people were tweeting about the phrase to demonstrate that members of the Proud Boys, who were present at the D.C. rally, were anti-Semitic.

Around 1:30 p.m., one Twitter user posted a series of tweets claiming that an ambiguous black-and-white flag bore the “6MWE” slogan. (Other Twitter users claimed it was a swastika flag. The 7-second video of the flag is unclear on both counts and more definitive footage does not appear to have circulated.)

By that evening, as the country grappled with the fallout of the violent attack, people were tweeting about the shirt as if it came from Wednesday’s rally. One of the first viral tweets about the photo came at 9 a.m. Thursday and was shared more than 20,000 times, juxtaposing the image with a photo of the “Camp Auschwitz” shirt. JTA reached out to the author of the tweet later that day, after spotting the error, and has not received a response. On Saturday, the author tweeted in a separate thread that the image was not from the rally, though the original tweet is still up.

One of the many people who shared that tweet was Deborah Lipstadt, the Holocaust and anti-Semitism scholar. Lipstadt, who has researched Holocaust denial and famously rebuffed a libel suit against her by a Holocaust denier, sent another tweet two days later when she became aware the photo was not taken on Wednesday.

She said that the episode was another reminder to “check before you post, check before you hit send.” That’s especially true, she suggested, because the far-right conspiracists she opposes, like Holocaust deniers or adherents of the QAnon movement, are often themselves fueled by the viral spread of misinformation.

She knows, from her research and personal experience, how Holocaust deniers will use purported discrepancies to try to discredit historical fact, such as by fixating on supposed inconsistencies in the ink in Anne Frank’s original diary. But she said that spending time worrying about the claims of extremists is a waste, because they don’t care about facts and standards of evidence.

“They’ll discredit it anyway,” she said. “We can’t live our lives always on the defensive. But when you know you’re dealing with a topic about which people are going to want to sow doubt or discredit, and it’s such an important topic, be careful.”

Talia Lavin, a researcher on extremism whose recent book, “Culture Warlords,” details her experiences infiltrating far-right internet communities, told JTA “anyone talking about or reporting on far-right events should strive for accuracy.”

But she added that the photo in question was likely from “events from a month ago — the same group, and the same city.” And she said that given the nefarious causes these groups promote, sharing evidence of their hate isn’t the worst thing.

“Spending our time worrying about how extremists are going to react to being portrayed as extremists is not a productive set of worries,” said Lavin, who worked at JTA for about a year starting in 2013.

Lavin knows how intense the blowback from an erroneously identified photo can be. In June 2018, she briefly tweeted that a tattoo on the arm of an ICE officer, in a photo shared by the agency, might be a Nazi symbol. She quickly deleted the tweet after realizing soon afterward that she was mistaken, and tweeted an apology. But ICE seized on the tweet, condemning her in a press release by name (though her name was misspelled). In the fallout from the tweet, Lavin resigned from her job at the New Yorker, where she was a fact-checker.

“Liars and abusers will deflect from their own malefactions by portraying innocent mistakes as some form of plotting,” she said. “They’ll use good-faith errors to try to derail conversations and to draw conversations away from their own bad actions.”

That doesn’t take away from the need to take a closer look at what we share online, Lavin said. But she said that the verified hate on display Wednesday was bad enough. There’s no need to stretch the truth.

“Of course it’s incumbent on all of us to practice good informational hygiene,” she said. “These groups are so malevolent that they hardly need further punching up. They hardly need exaggeration here.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.