BELFAST, Northern Ireland (JTA) — Since last week, Northern Ireland’s capital has been plagued by familiar scenes: rioting, the gray shells of burned-out cars, injured police officers.

For many in this post-industrial city of 280,000, it has conjured memories of the Troubles, a three-decade period of sectarian violence that left thousands dead and pushed thousands of others to leave.

But as it was throughout the worst of the Troubles, Belfast’s tiny Jewish community — much smaller than it used to be, down to about 30 households from a peak of 453 in 1977 — is not overly concerned about the new conflict, which has boiled over due to Brexit complications and other unresolved British-Irish tensions.

Michael Black, the community’s chairman, told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency last week that he hopes the violence will “peter out” soon.

“Thankfully the few areas that are rioting are not near the shul or where the Jewish community live. We only feel threatened when there is a problem in the Middle East,” he said, referencing the anti-Israel sentiment that runs strong throughout Ireland.

Just like in the 1970s, the feuding protesters are broadly split into two groups: Irish Republicans, who want a united Ireland, and British loyalists, who want Northern Ireland to remain a part of the United Kingdom. The loyalists, angered by part of the Brexit deal that has set up a trade barrier in the Irish Sea, have been the main instigators of the current protests. The trade wall has effectively left Northern Ireland using European Union market rules, leaving many infuriated loyalists feeling like the country is treated differently than the rest of the U.K.

The last straw for them was a large funeral for IRA member Bobby Storey, which drew lawmakers and disregarded social distancing guidelines despite taking place at the height of the COVID pandemic.

Nationalists attack police in Belfast, April 8, 2021. (Charles McQuillan/Getty Images)

But there is also an ethno-religious divide between the two sides: the Irish Republicans are largely Catholic, the loyalists largely Protestant.

Because local Jews avoided taking a side on the religious front, they have been — and still are — seen as neutral onlookers. In some cases they were even involved in attempts at reconciliation between the two groups.

But that doesn’t mean the Jewish community left the Troubles completely unscathed.

A thriving “shtetl”

As 1970 dawned and Belfast was plunged into violence, the city’s Jewish community was thriving in a social sense.

Former member Keith Daly said that growing up Jewish at the time felt “like the shtetl from Russia moved to Belfast … so when we grew up it just felt like family.”

Many Northern Irish Jews in the province were the descendants of Ashkenazim who had fled pogroms in Eastern Europe and later the Holocaust. On their way to America, some decided to settle and build a community in Northern Ireland instead of making the journey across the Atlantic.

Many have attributed the success of the community to the Belfast Jewish Institute — locally nicknamed “the club” — which was a short walk from the synagogue situated on a leafy street in the northern part of the city. One ex-community member named Ben (like others in this article he refrained from providing his last name for safety reasons) called the club “a huge, central part of the community.” It offered its members tennis courts, a ballroom, card rooms, a drama society, a debating society, a kosher restaurant and more. It entertained esteemed guests, such as ceremonial lord mayors and chief rabbis.

While the city around it occasionally erupted into literal flames, or the sound of bombs blowing up could be heard nearby, the club acted as a literal sanctuary for the Belfast Jewish community.

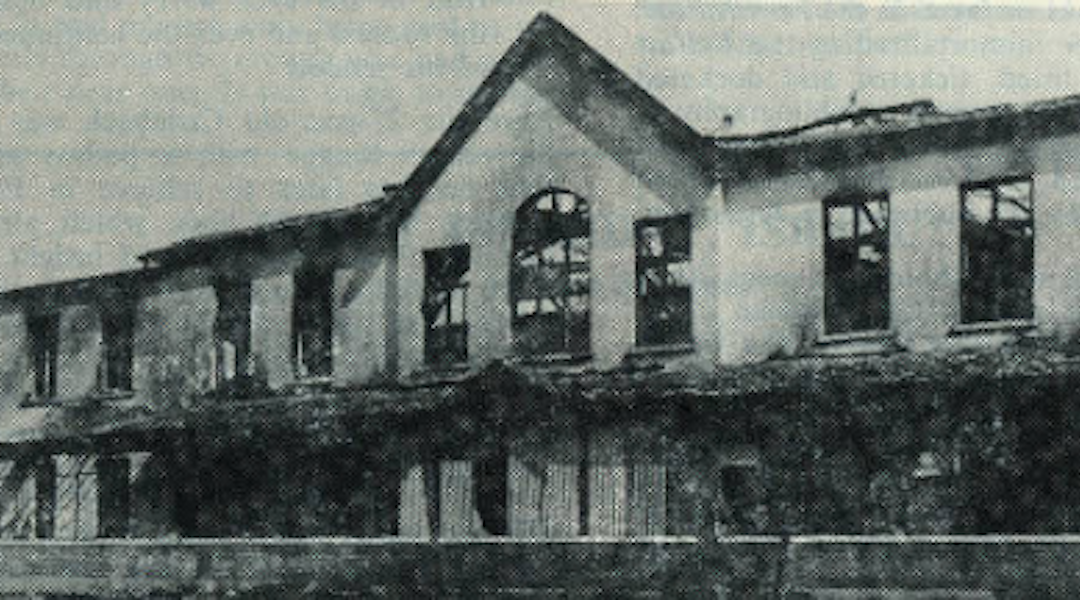

A view of “the club,” where Belfast Jews used to socialize in its 1970s heyday. (Courtesy of Belfast Jewish Community)

For a provincial area that struggled to attract any tourism during the conflict, Belfast had everything going for its tight-knit Jewish community in the early ’70s: a synagogue that was full every week; a booming social life at the club; and amenities not found in other small communities in Great Britain, such as a kosher butcher who came to the doorsteps of Jewish families in the northern part of the city.

Staying out of the conflict allowed community members to relatively prosper financially, and they were held in high esteem throughout the Troubles for their important contributions to Belfast over time. For example, a Jewish family was instrumental in Northern Ireland’s booming linen industry, which cemented Belfast as an enviable industrial city in the 19th century. Later on, many Northern Irish Jews owned family-run businesses, and became doctors and other professionals.

‘The thing went boom’

If it seemed too good to be true, it was. Some 3,700 people died in the conflict, many of them uninvolved civilians, and eventually it hit the Jewish community.

On Feb. 8, 1980, Leonard Kaitcer, a husband with two sons and a beloved member of Belfast’s Jewish community, was dragged from his home and kidnapped by gunmen. He was an antiques dealer who owned a shop in the city and his kidnappers had demanded a ransom of 1 million pounds, nearly $1.4 million, for his release. When Kaitcer was unable to hand over such a huge amount, he was shot dead.

While no paramilitary ever took responsibility for the murder, kidnapping was a tactic employed by many Irish Republican groups as part of a campaign to devastate the British state and its economy, and to fund its weaponry.

At the time of Kaitcer’s death, sectarian murders were a norm, but a local Jewish man, Steven Jaffe, said his community was especially devastated because of how hard they had tried to avoid the conflict.

“[Kaitcer’s] murder shocked people in a way because the sense was that this had nothing to do with the Jewish community,” Jaffe said.

Children hijack vehicles to celebrate the shooting of a British soldier by an IRA sniper in West Belfast, April 12, 1972. (Alex Bowie/Getty Images)

Kaitcer’s funeral was the largest ever Jewish one recorded in Belfast and was seen as symbolic. The Belfast Jewish Record reported at the time: “[O]ur own small community came to join the parents in mourning a son, a host of friends came to pay their last respects and many more, unknown and unrecognised came simply to share our grief and make silent protest against the savagery that has overtaken our country.”

The Kaitcer murder, along with other random, less serious attacks on Belfast Jews at about the same time, prompted many families to flee the city and immigrate to Great Britain. Some left for Israel.

Following the pattern of other small British Jewish communities — such as in Newcastle and Cardiff, whose members gradually moved to larger communities in cities like Manchester and London — the Belfast community was actually already in slow decline numbers-wise in the 1960s. Belfast Jews had to look elsewhere for university and professional work, as well as to marry into the faith if they wanted. But the Troubles accelerated the exodus.

Keith Daly recalled being 7 or 8 years old, waiting in line at a newsstand, when a woman came rushing into the shop, panicking and sputtering that a bomb was about to go off at the police station a few shops down. As Daly had been out for a while, his mother had sent his brother to the store to see why he was taking so long. When Daly told him about the bomb, his brother grabbed him and they bolted across the street.

“As we ran out of the newsagent store and across that first street, the thing went boom and the bomb went off, and all I really remember about that experience was that I was holding [my brother’s] hand and we were jogging and then we were sprinting as fast as we could, smoke and bricks and stones flying by,” Daly said.

They ran home.

“My mother had my younger brother in her hands and threw him at my grandma,” Daly recalled. “She ran down the driveway and said when she got to the gate, all she could see were two kids in their school uniform running out of the smoke.”

The current struggle

For many Jewish families, moments like these became the final impetus to leave Belfast.

Gillian Rowe Price, an expatriate of the community, remembers being “whisked away” by her parents at short notice to go to Manchester, a city with a larger Jewish population in England. Other families followed suit.

In 1977, there were 453 households affiliated with the synagogue in north Belfast, Northern Ireland’s only Jewish house of worship. In 1983, there were 312. By 1990, the number had dropped to 221. Today there are just over 30.

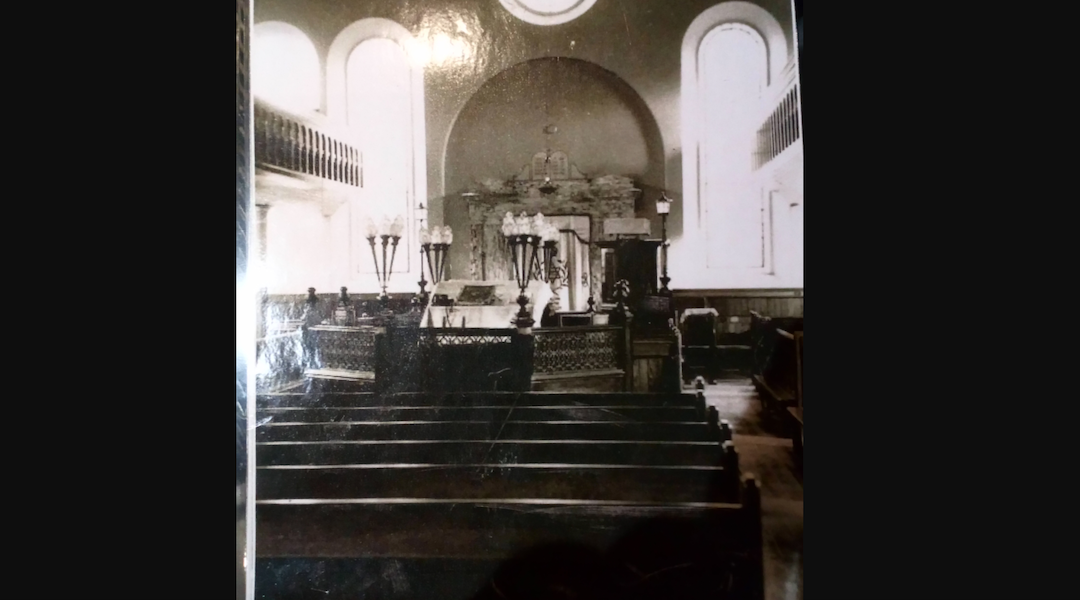

A photo of the old Belfast synagogue. (Northern Ireland Friends of Israel)

As the community began to decline at a steeper rate — arguably when the Troubles was at its peak, in the early 1980s — the Belfast Jewish Record reported that “each departure is a grievous loss to the small community, one which we can ill afford.”

“The cumulative effect is indeed serious and will inevitably bring about much soul-searching,” the report continued. “Obviously, there will have to be a serious reassessment of the communal institutions and the maintenance in the light of the reduction in numbers. Like it or not, the whole future of this community is now in a state of flux and its condition must be continuously under review.”

The thriving state of Jewish life declined, along with everything else.

Shoshana Appleton, who was born in Jerusalem but moved to Northern Ireland to marry Belfast-born Jew Ronnie Appleton, remembers how challenging Jewish life was at the time. Her husband was chief prosecutor for Northern Ireland for 22 years, so their family had 24-hour police protection, as they would have been likely targets for paramilitaries.

For their son’s bar mitzvah, they needed a big batch of kosher meat that was supplied only in Dublin, south of the border. But the border was tightly controlled, and cross-border food trading was prohibited. So Shoshana’s husband was driven, secretly, by a police escort to the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland where British soldiers stationed in Northern Ireland and Gardai, members of the Irish police force in the republic, watched as kosher meat hidden in black bin liners was smuggled from one side of the border to the other. The plight was onerous, but it made certain that the bar mitzvah guests would not go hungry.

It also became nearly impossible to attract rabbis to stay at the synagogue during the conflict. The Belfast Hebrew Congregation was once led by Rabbi Isaac Herzog, who later became the chief rabbi of Israel, and whose Belfast-born son Chaim was president of Israel between 1983 and 1993. Despite such an impressive past, the synagogue had no rabbi at all between 1979 and 1983. And the rabbis they did manage to attract stayed sometimes for a matter of months before Belfast’s violence took its toll and they fled the city for Jewish life elsewhere.

(Today the synagogue has a Jewish “reverend” named David Kale who leads services and acts as a cantor, despite not being ordained as a rabbi. He has explained that “A reverend is an experienced and qualified person who is authorized by the chief rabbi of the United Kingdom and Commonwealth to carry out all the duties of a rabbi.”)

The club, which had been dilapidated for a while because the community could no longer afford its upkeep, was burnt down by vandals in 1982. This wasn’t an anti-Semitic attack, Black said — burnt-out buildings were a feature of Belfast’s landscape at the time.

The ballroom that Belfast’s Jews had once danced in was unrecognizable. The Belfast Jewish Record described the club’s remains as a “charred skeleton.”

To replace the club, the community decided to adopt a smaller social center on the same site as the synagogue, but by the 1990s even that was ill-afforded. The shrinking community meant that there were fewer families contributing to its finances. Eventually that building was sold, and instead they sliced the synagogue itself in half, allowing part of it to become a social center. This is how the synagogue site remains today.

Northern Ireland’s Jewish community is one “dying on its feet,” Appleton said. But regardless, in her view, the community remains as welcoming and friendly as it always had been.

“A lot of people wouldn’t believe you because of the Troubles, but it’s a lovely place. A warm place,” she said. If people came to join or visit the community today to keep it alive, she told JTA, “that would be a great mitzvah.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.