(JTA) — Ephraim Einhorn, a rabbi and businessman who helmed Taiwan’s fledgling Jewish community after a career that included clandestine missions on behalf of oppressed Jews, has died.

Einhorn’s death on Wednesday morning in Taipei, just hours before the beginning of Yom Kippur, came after an extended illness and weeks of intermittent hospitalizations. He had turned 103 three days earlier.

Einhorn was Taiwan’s first resident rabbi and, for 30 years, the only one to serve the community that now includes an estimated 700 to 800 Jews. He was also a teacher, diplomat, businessman, scholar and father whose personality loomed large.

“He was sometimes impatient with people and could be intimidating. But at the same time you felt underneath that layer there was a great deal of kindness and empathy,” said Don Shapiro, a former president of the Taiwan Jewish Community group, who first met Einhorn in the early 1980s. “So he was a very complex individual. I don’t think I’ve ever met anyone else even closely like him.”

Einhorn’s life spanned a century of upheaval and renewal for the Jewish people. Born in Vienna in 1918, he attended several yeshivas across Europe before moving to the United Kingdom. (His parents, who remained in Austria, were murdered by the Nazis.) According to his retelling, he gained admission not by applying in the regular manner, but by impressing rabbis with his mature knowledge and fantastic memory of proverbs his rabbi father encouraged him to memorize when he was young.

After earning both rabbinic ordination and a doctorate in philosophy from a London yeshiva that is now defunct, Einhorn began working with the World Jewish Congress, first in England, and later in the United States, where he simultaneously led several congregations as a rabbi in the late 1940s through the 1950s.

His position with the World Jewish Congress included “often-clandestine missions to countries in North Africa and the Middle East to try to help Jewish minority communities facing persecution,” according to AmCham Taipei, an American business group in Taiwan that honored Einhorn in 2016.

On one mission to Iraq in 1951, according to WJC archives, Einhorn posed as a Protestant minister to investigate a group of Iraqi Jews who had allegedly been tortured under the suspicion of being Zionists. Einhorn boasted about the mission to local papers in Detroit, where he was serving as a rabbi at the time, even though he was not authorized to discuss it publicly.

He had a “passion for publicity,” a top WJC official, Maurice Perlzweig, said at the time. Einhorn remained involved in the organization in following years, but Perlzweig wrote to other officials that the organization would no longer support his frequent international travels, as there was “an infinite possibility of mischief if he were let loose.”

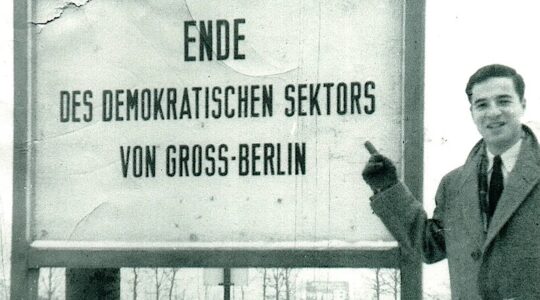

By the next decade, Einhorn began pursuing business activities that would take him to far-flung, often otherwise hard-to-access locations. He founded the World Patent Trading Corporation in 1968 and opened an office behind the Iron Curtain in Prague, where he had family. But by 1973, he was expelled from Czechoslovakia for activities that Soviet leaders said were “incompatible with the interests of the State” but did not detail publicly, according to a Jewish Telegraphic Agency report from the time.

In 1975, Einhorn arrived in Taipei as a financial advisor on a Kuwaiti trade delegation. Already almost 60 years old, Einhorn had an impressive resume. He spoke seven languages (though he never learned Chinese), and upon meeting people, he handed new acquaintances a stack of roughly a dozen business cards: chairman of Republicans Abroad in Taiwan, vice president of the World Trade Center Warsaw, honorary representative of the Poland Chamber of Commerce, and on and on.

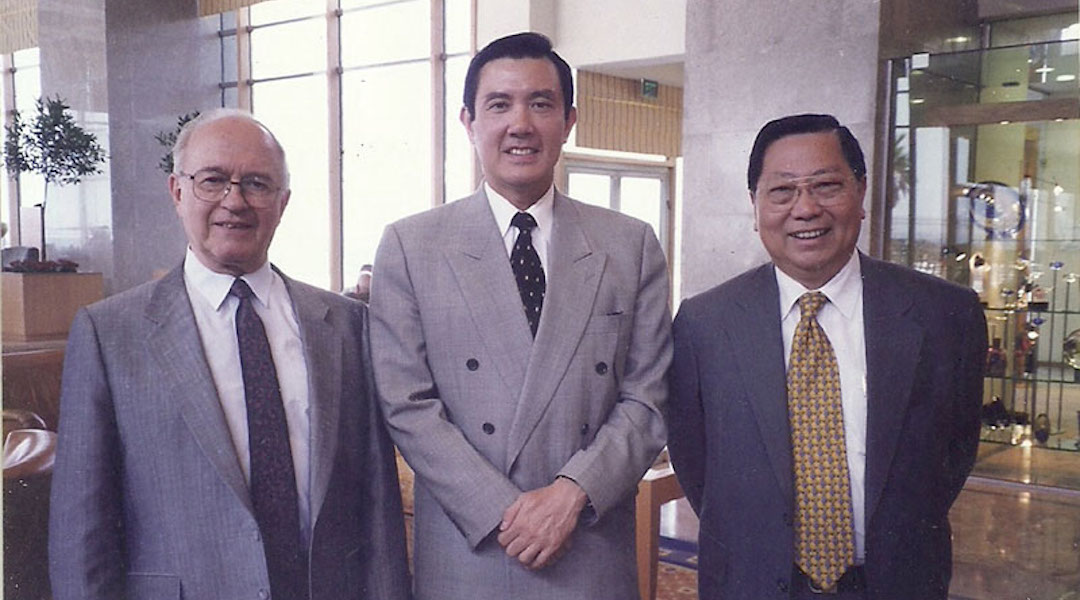

From left to right: Einhorn, then-Taipei mayor Ma Ying-jeou and Taiwan’s representative to Israel R.T. Yang, in the early 2000s. (Courtesy of Einhorn)

When he began officiating bar mitzvahs and holding holiday services, some within the Jewish community were justifiably skeptical; he didn’t tell people much about his past. Some wondered if he was working for Mossad or the CIA, according to people who were part of the community at the time.

“He wasn’t very popular in the old days and people were a bit suspect about people working with Arab countries,” said Fiona Chitayat, a former longtime community member.

She added, “All I know is that he had unbelievable connections in Taiwan.”

Often, Einhorn used those connections to help people. He bailed fellow Jews out of jail, helped them resolve visa issues and once even helped arrange a special medical flight with the assistance of contacts he had met in his business and political ventures in Taiwan and beyond its borders.

“He was very closely related to some formerly Eastern European countries, and he personally went out of his way to help our diplomats there,” said Leonard Chao, who had previously worked for Taiwan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Einhorn helped Taiwan establish early connections with countries like Poland, the Czech Republic and Hungary, among others, in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Always one to claim center stage, Einhorn opened his own congregation in 1979 at the President Hotel, and later the Ritz Hotel. After joining forces with the Taiwan Jewish Community around 2000, he chose to keep his congregation separate when Chabad Rabbi Shlomi Tabib arrived in 2011 and offered to work together.

Einhorn led Taiwan’s Jews in worship for more than four decades, even as the number attending services waned to fewer than the 10 required for many prayers for several years in the 2000s, and even as his health began to decline more recently.

“I am the rabbi, the shamash and the treasurer. And I pay all the bills,” Einhorn told JTA in 2007. “Somebody’s got to do it.”

Though he was trained as an Orthodox rabbi and worked in Orthodox synagogues in North America, Einhorn maintained a congregation that was open to all — including non-Jews who were interested in converting or even just observing. Taiwan Jewish Community events drew attendees from across the local community and even included an in-person Passover seder this spring, one of the only sanctioned communal seders in the world because COVID-19 was well controlled in Taiwan at the time. Einhorn was present.

A group photo at the Jewish Community of Taiwan’s 2021 Purim party, where no masks were required. Rabbi Ephraim Einhorn, in a wheelchair, can be seen at the front left. (Archi Chang)

In 2019, as leading holidays and weekly services independently became more difficult for Einhorn, the community invited a cantor, Leon Fenster, who had previously spent time as a religious leader in Beijing, to assist him and help lead the community. Fenster will now take over for him.

“We have to be very grateful to [Einhorn] for having preserved the elements of Jewish life that have continued in Taiwan,” Shapiro said. “Without his presence here before Chabad, and over quite a few decades, things would have turned out very differently.”

The community’s loss was still fresh in the hours after his death, when local Jews came together for Yom Kippur services, the first High Holiday without him in decades.

“Dr. Einhorn in my opinion was the one thing that gave consistency to the Jewish community over the past 50 years and will be missed by many as the Jewish Community of Taiwan moves into a new era,” said Jeffrey Schwartz, an American businessman who has been involved with the community since his arrival in the 1970s and will open a new Jewish community center in Taipei this winter.

Einhorn especially loved to learn and teach. His door was always open to people who had philosophical or religious questions, and his vast library — which Einhorn claimed was the biggest collection of Jewish books in Asia — was always on loan.

“Some people buy clothes, some ladies buy bags. He buys books. It was the only thing he spent his money on,” said Yoram Ahrony, an Israeli community member who has been close with Einhorn for almost 40 years.

Researcher Jonathan Goldstein described Einhorn as a community storyteller, calling him “the maggid of Taipei.” An interview from 2010 that religious scholar Paul Farrelly conducted with Einhorn shows his philosophy of openness, and passion for learning by teaching.

“Everybody has something to say, to make a contribution. Everybody has a point of view,” Einhorn said. “To know what you don’t know is the beginning of wisdom … most wonderful thing in the world is to say, tell me, I want to learn.”

He will be buried in Petah Tikvah, Israel, and is survived by his longtime companion Eugenia Chien; two daughters from his marriage to Ruth Weinberg, Daphna and Sharone, living in the U.S.; and grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.