Editor’s note: Before working for the Jewish Telegraphic Agency’s sister site Alma, Emily Burack worked for a year on “Meir Kahane: The Public Life and Political Thought of an American Jewish Radical” as author Shaul Magid’s research assistant. She wrote her undergraduate thesis, cited in Magid’s book, on the emergence of the Jewish Defense League.

(JTA) — Meir Kahane is the “Jew whom Jews would like to forget.”

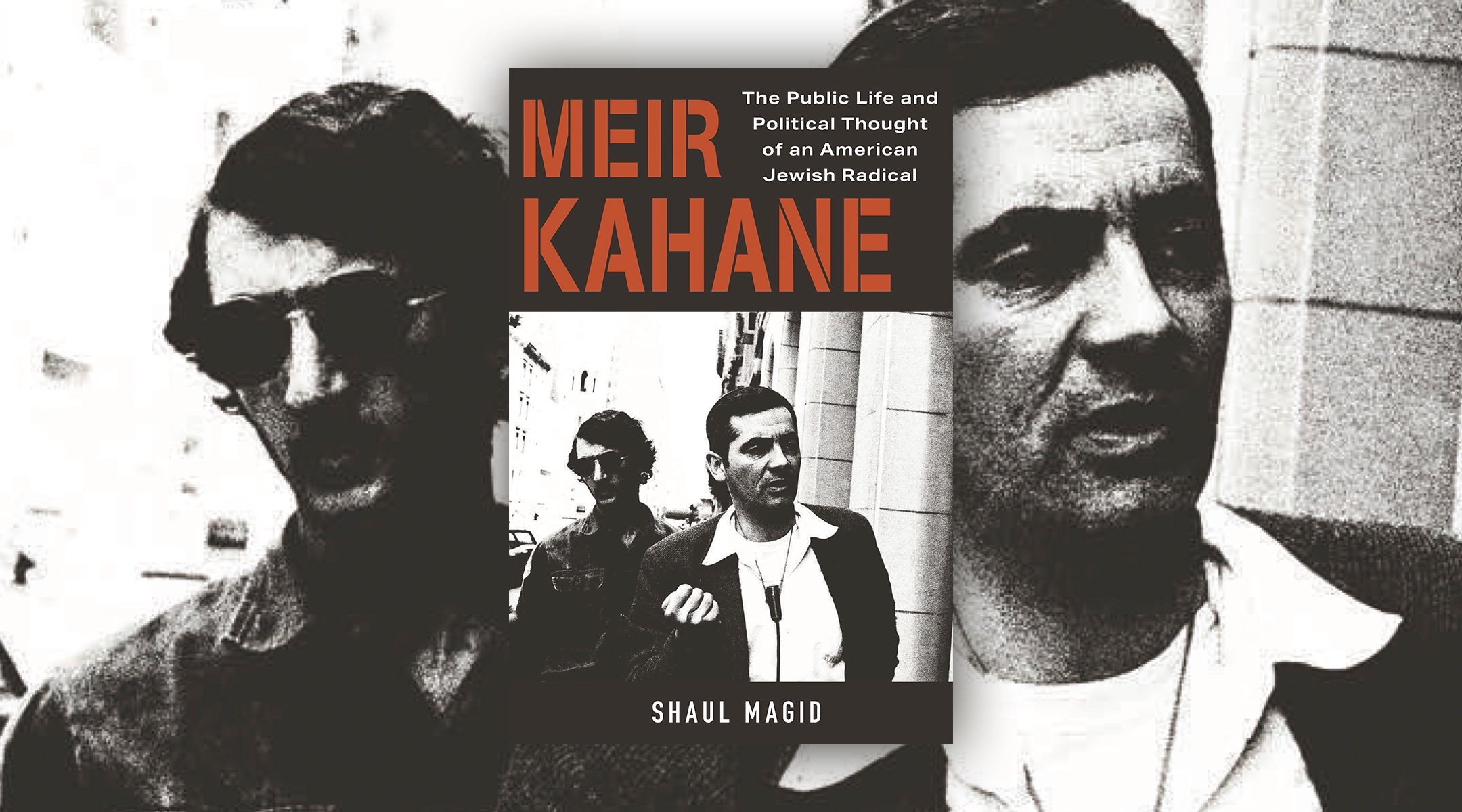

Yet, as Shaul Magid writes in “Meir Kahane: The Public Life and Political Thought of an American Jewish Radical” (Princeton University Press), his new cultural biography of the controversial Jewish figure, Kahane keeps coming back to haunt us.

Born in Brooklyn in 1932, Kahane was elected to the Israeli Knesset, or parliament, in 1984 on an extremist platform calling for Arabs to be expelled from Israel, among other ideas. In 1986, under a new “anti-racism law,” he was barred from running for re-election. In 1990, he would be assassinated by an Egyptian American in New York City. In today’s Knesset, the Kahanist party Otzma Yehudit (literally, Jewish Power) has one seat.

But in 1968, before his time in Israel, he founded the militant Jewish Defense League. Focused on Jewish pride, Kahane called for “every Jew a .22” and popularized the slogan “Never Again.” He spoke out against intermarriage, believed a second Holocaust was inevitable and that antisemitism was a pervasive threat on the left and right, accusing less confrontational Jews of lacking Jewish pride.

Although his militant and violent tactics alienated the Jewish mainstream, he was a key figure in publicizing the fight to free Soviet Jewry. Ultimately he pivoted to what Magid describes as “militant post-Zionist apocalyptism.”

Magid’s book tells the story of Kahane’s radicalism — from his critique of liberalism through his ever-changing Zionism.

“He became demonized because of his tactics, and because of his violence and his racism. But the worldview has really dug some pretty deep roots,” Magid said. In “Meir Kahane,” he sets out to unpack how that worldview lingers today, and he spoke with JTA about the project.

This conversation has been lightly condensed and edited for clarity.

JTA: To begin, you write about how Meir Kahane’s ideas, and much of what he promoted in America, have entered our mainstream discourse, like that antisemitism is pervasive everywhere, or his, as you write, “assertive expression” of Jewish identity. As someone who studies Kahane, what is it like to see his ideas enter the mainstream?

SM: You have to make a sharp distinction between his worldview and his tactics. His militancy was very much a product of his time. He was living at a time of the Black Panthers, the Young Lords, the SDS [Students for a Democratic Society], the Weather Underground; the idea of radical militancy and violence was very much a part of what was happening in America at the time. That, of course, has fallen away, in most cases.

If you take that [militancy] away, it’s not that Kahane disappears, but what you actually have is a much more well-defined worldview that has really made its way into the subconscious of American Jewry: perennial antisemitism, antisemitism on the left is worse than antisemitism on the right, anti-Zionism is antisemitism. What we call now “Jewish continuity,” Kahane just called “Jewish survival.” The idea of Jewish pride: How do you actually create an environment where Jews can be proud to be Jews in an unashamed way? Questions of intermarriage — Kahane wrote a book about intermarriage in 1974 when nobody was talking about intermarriage. He saw into the future a bit on some of these questions.

Shaul Magid (Courtesy of Magid)

In your book, you emphasize that Kahane was a quintessentially American figure. Much of previous scholarship on him focused on his time in Israel, and looked back on his time in America through that lens, but you argue we need to reverse that — understanding him in America is key to understanding him in Israel.

He fails in Israel because he’s bringing American categories and an American way of seeing society to an Israeli society which is very different. It’s more complex in all kinds of ways. First of all, in Israel, the Jews are the majority, not the minority, and that itself changes things. [Second,] he couldn’t re-conceptualize the complexity of race in Israel from the much more straightforward understanding of Black and white in America. As a result of that, he succeeds initially — he is elected to the Knesset — but ultimately the country rejects him.

Yet in both places, Kahane used racist language to further his base and make a name for himself.

Kahane uses race in very interesting ways. I don’t necessarily think that they were all worked out in his head. He saw race as a pivotal issue in America in the 1960s. He was very, very impressed by the Black nationalism of Black Panthers, and he saw the way in which they were able to cultivate a reaction to the racism that they were confronted with in ways that help produce their own sense of identity. And he tried to do the same thing, I think, with Jews. He didn’t call Jews a race because Jews didn’t call themselves a race at that point anymore, but he certainly saw race as an important issue.

In Israel, it’s actually pretty different, because race is a much more complicated story there. Ultimately, the conflict between the Jews and the Arabs is not really a racial conflict the way the conflict between whites and Blacks was in America. A lot of people say, oh, race is not really an issue in Israel, it’s really about dual nationalisms, or whatever. I think that’s also wrong. I think religion is very much at play, and obviously, national identities are very much at play, and I think race is at play, too.

In terms of Kahane’s language of Jewish power and Jewish pride, why is that not as successful in Israel?

Because you have Israeliness. Jews can be proud of being Israeli; they can be proud of being Jews; they can be proud of being religious Jews; and it’s the majority culture. So you don’t need to cultivate that identity of pride in the same way that you do when Jews are a minority. Israel is facing antisemitism in a very different way than American Jews are. Israel is facing antisemitism as a collective, perhaps, but not necessarily as individuals. Whereas in America, Jews are facing antisemitism as individuals.

It’s different to talk about Jewish power in America than talking about Jewish power in Israel, where actually Jews are the power. They have the power, they have the military, they have the police. I mean, the structure of the society is about Jewish power.

In the chapter on Zionism, you write about how he’s saying Israel can’t be both a Jewish state and a democracy, which was, correct me if I’m wrong, controversial to say back then. But we hear that all the time now.

It was controversial back then, but only for people in the center and on the right. People on the Israeli left were saying Israel can’t be a democracy and a Jewish state from early on. You had groups like Matzpen that were basically anti-Zionist precisely because of that: They wanted a democratic state, not a Jewish state. Kahane was saying it as a Zionist; he calls Israel schizophrenic in his 1986 book “Uncomfortable Questions for Comfortable Jews.” [For Kahane,] it just doesn’t work, so you have to choose: You want to have a Jewish state, or you want a democratic state.

This also has to do with Kahane’s Americanism. For him, there was only one kind of democracy: the American style of liberal democracy. That was it. If you live in a democracy, then everybody that lives in that democracy has to be treated equally. So later, when the Jewish and democratic equation started to become more complicated, people came up with other theories, like “ethnic democracies.” Kahane’s line is like, “No, no, no. There’s no Jewish democracy or Arab democracy, there’s just democracy or no democracy.”

Do you see this idea taking hold today more prominently?

Oh, sure. We’re basically living on the verge of a post-two state Israel, where the Palestinians are not going to be given a state, where they’re not going to be citizens, and they’re going to be ruled over by Israel. If this is being done in order to ensure a Jewish state, what Kahane would say is, “okay, so that’s not a democracy anymore.” And a lot of people are saying that. If the Jews today are being confronted with a Jewish state or a democratic state, more and more are leaning toward a Jewish state.

Which is what Kahane would’ve wanted…

Well, he would’ve wanted it, but not in that way. Kahane basically gives up Zionism at some point, he realizes that it’s just a failed liberal project of “Hebrew-speaking goyim,” or “Jewish Hellenism,” or all these things that he called it. In other words, for him, Zionism failed. It failed to produce a true Jewish state.

“Meir Kahane: The Public Life and Political Thought of an American Jewish Radical” tells the story of Kahane’s radicalism — from his critique of liberalism through his ever-changing Zionism. (Princeton University Press)

There has been a lot of consternation about Itamar Ben-Gvir, a disciple of Kahane, entering the Knesset. What do you think his election says about Israeli society, and how does his being in Knesset compare to Kahane himself being in Knesset in the 1980s?

Ben-Gvir, and [current Knesset member] Bezalel Smotrich in a different way, and a number of other Israeli parliamentarians somehow identify with Kahane. I think they’re really better understood as neo-Kahanists. Meaning, they come from the religious national educational system, the system of Rav [Abraham Isaac] Kook, [the first Ashkenazic chief rabbi of what was then Palestine], and there’s a certain kind of theological romanticism that underlies their thinking.

They’re not like [Israeli far-right politician] Baruch Marzel, a real Kahanist: For him, it doesn’t matter what the rest of the world thinks. He’s a leftover version of Kahane — which is, “we’re really talking about power and conquest. We don’t have to make excuses. We don’t have to say, oh, we’re doing this because of security reasons. We’re doing this because God gave the Land of Israel to the Jews. And that’s what we’re living out.” In a way, the neo-Kahanists are always trying to kind of construct a Kahanist vision that contains a certain kind of normalization apologetics that Kahane just didn’t have. Because ultimately, Ben-Gvir believes in the secular state. Kahane didn’t believe in the secular state.

What do you think of Kahane’s legacy in the American Jewish community today, in terms of what it means to be a Jew in America, a proud Jew in America?

One of the things that’s happening in American Jewry today is all of this discussion about defining antisemitism. American Jews are feeling newly unsure whether America can ultimately protect them. That brings us back to what Kahane was feeling in the 1960s and 1970s: America has been better to the Jews than any other country in Jewish history, but antisemitism will always rise to the surface, and that Jews could never feel comfortable there. He’s giving up on American Jewry, saying that, as long as America remains a liberal society, it will ultimately not protect the Jews. Not that the Jews are going to feel physically endangered, but they’re also going to feel spiritually endangered because they will be asked to give up their own sense of Jewish identity.

Kahane was speaking before the rise of multiculturalism, and multiculturalism may have changed that. He was living in an America where assimilation into Americanness meant a diminishing of one’s particular identity. Multiculturalism creates a different cultural model where difference is celebrated, rather than only tolerated. What Kahane felt was the danger of the American embrace of the Jew in the 1960s and ’70s. In the 1990s and the 2000s, through multiculturalism, I don’t think that’s necessarily as true anymore. We can talk about the rise of Orthodoxy in the 1980s and 1990s. Why does Orthodoxy come back into fashion? In large part it’s really riding the wave of multiculturalism — it has nothing to do with Orthodoxy per se.

You speak about how he predicted a lot of the issues that the American Jewish community are struggling with today, but he kept making the same mistake over and over again. Where do you view him failing in his tactics?

Violence, that’s number one. Second of all, he always went too far, he always overextended. And [third,] he had this maniacal desire for power, his own personal power, that ultimately undermined it.

What’s an example of Kahane undermining himself?

I don’t think Kahane knew about the Sol Hurok bombing. [The Jewish Defense League, opposed to Soviet artists performing in the United States, bombed theater impresario Sol Hurok’s offices in January 1972, killing a young Jewish woman, Iris Kones.] I don’t think he knew what was going to happen. I think that he had lost control of the JDL by then. I think that he was horrified by it, but I think that he set something in motion, and at some point, you can’t necessarily control what’s going to happen and you still have to take the responsibility for it. After Sol Hurok, it all basically just started to collapse. The irony is that wasn’t even his fault. He wasn’t even there, and he probably didn’t even know it was going to happen.

And yet, he goes back and defends the guys who did it.

He goes back and he stays in America longer than he was planning to because he wanted to defend them. He tried to do damage control, but that was not an operation that he gave the green light to. I think the JDL was functioning without him by that point. Once you get to 1973, 1974, the JDL was dysfunctional; it had lost the vision that Kahane had for it.

While we’re talking about violence, I’d be remiss not to bring up the Baruch Goldstein massacre in Hebron. Goldstein, an American Israeli physician and onetime JDL member, perpetrated the 1994 Cave of the Patriarchs massacre, killing 29 Muslim worshippers and wounding 125, before he was beaten to death by survivors. Do you view the massacre as directly part of Kahane’s legacy in Israel?

Definitely, definitely. In Kiryat Arba, which is the Jewish city buttressing Hebron, there’s a place called Kahane Park.

And Goldstein’s buried there, right?

Exactly. It’s certainly part of that.

One of the other things I hope is that [the book] sparks a much more nuanced conversation about Judaism and violence. And not this kind of “Judaism is nonviolent.” No, Judaism is not nonviolent. Because no religion is really nonviolent.

He was constantly discussing examples of Jewish violence and revenge. You see that early in “Never Again” and the JDL, and you see that in “The Jewish Idea,” and his very militant vision of Judaism.

The two things [he cites]: one is Moses smiting the Egyptian [in Exodus 2:12], the other is the midrash about Abraham destroying the idols in his father’s idol shop. He’s basically saying Jews misunderstand violence. Kahane thinks that this whole “Jews are against violence” is a product of centuries of Diaspora living where Jews are just trying to survive the violence that’s happening to them. For Kahane, the true tradition of Jewish history is really one of violence and militancy and rebellion.

“Never Again” was one of the very first books he wrote, and we’ve really seen the phrase “never again” become popular today. It’s something I think about a lot, how this was the slogan of the JDL, the name of his book, he was talking about a second Holocaust in way that I’m not sure others were. How do you understand Kahane’s vision of “Never Again” resonating today?

“Never Again” sold 100,000 copies in the first year; none of his other books were that successful. It touched a nerve of a certain kind of anxiety, and also a certain kind of assertiveness that children of Holocaust survivors and first generation American Jews — who had been affected by the counterculture, and had become alienated from the New Left after 1967 — he basically allowed them to become radicalized as Jews.

The problem with Kahane is that people love him and people hate him, but nobody actually reads him. It would be interesting to do a reading of “Never Again” among a group of liberal American Jews, because of the way he makes fun of the American bar mitzvah, the way he makes fun of the opulence of Great Neck and Scarsdale. His critique of classism, his critique of Jews abandoning elderly Jews in Bed Stuy and Crown Heights — I mean, in a certain way, if you read that book, without the rest of the history of Kahane, I think it still resonates in some way.

We didn’t even touch on Soviet Jewry at all, but you talk about how he brings Judaism and ritual into protest. I feel like that is the cornerstone of American Jewish leftist protest movements today.

Totally! I dedicated the book to my friend Aryeh Cohen, who’s a progressive leftist social activist, and yet was part of the JDL when he was young. I’ve said to him, “Aryeh, you don’t understand ‘the take Judaism to the streets’ that you’re engaged in while protesting for migrant workers and others. Where do you think you got that?” And he kind of laughs, he doesn’t really think that. But it’s true. Basically, Kahane was saying Judaism does not belong in the synagogue, Judaism belongs in the streets, it belongs in protests.

When people read “Meir Kahane,” whether they know him or don’t know him, what do you hope they take away from the book?

Certainly within academic circles, we missed something very important in the telling of the story of 20th-century Jewry. [Brandeis University historian] Jonathan Sarna’s “American Judaism” has no mention of Kahane. That was not by accident, that was an intentional erasure. That’s the first thing: We can’t ignore this person. Whether it’s like including him in syllabi, teaching him in courses, whatever it is.

For a more general audience, this is a figure who is incredibly important in terms of the cultivation of Jewish identity among Jews in America and in Israel after the Second World War. I hope that people start to read him critically, as part of the story and to say, “oh, how much of this has seeped in?”

Join JTA’s partner site My Jewish Learning for a Zoom book talk with Shaul Magid about his new book “Meir Kahane: The Public Life and Political Thought of an American Jewish Radical” on Oct. 13th at 4 p.m. ET. Magid will speak about this cultural biography of one of the most demonized yet influential figures in postwar Jewry, in both America and Israel. Click here to register.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.