(JTA) — When Seattle-based playwright and theater director Lauren Goldman Marshall first staged her original musical about the Israel-Palestinian conflict in 1991, she had recently embarked on a journey of self-discovery prompted by the First Intifada. Working alongside Palestinian collaborators, she produced a heartfelt show meant to celebrate “seeing the other.”

Thirty years later, that show, “Abraham’s Land,” has been revived for a new generation. A new adaptation was staged in Seattle this summer, and a filmed version is streaming for free online through Dec. 12.

But much has changed in the intervening decades, from the trajectory of peace efforts to sentiments among American Jews to ideas in the theater world about what constitutes meaningful representation on stage.

And now, several Palestinians who were involved in the first staging, including the play’s original co-author, have backed out of the project. They say the Jewish producers ignored their concerns about representation and a narrative they perceived as racist.

“This play has harmed Palestinians both on a political level and on an interpersonal level over its 30-year existence,” reads an open letter penned by Palestinians who had been involved in readings of the show. “This production and those behind it cannot continue to exploit our communities.”

At least one Jewish group is rethinking its support of the production in light of the public outcry: Kadima Reconstructionist Community, a Seattle-area congregation, withdrew its endorsement of “Abraham’s Land” following the open letter.

Other former collaborators say there’s nothing left the show can teach anyone.

“The play is outdated,” Palestinian-American playwright Hanna Eady, who co-authored the original show with Goldman Marshall, said about “Abraham’s Land” today. “It has nothing to do with what’s going on here, or what has been going on since the first Intifada — nothing.”

“Abraham’s Land” was originally inspired by Goldman Marshall’s reaction to the first Intifada in the late 1980s, during which she reconsidered her own relationship to Israel as an American Jew. She visited Israel, stayed in a Palestinian refugee camp and held a conversation with Israeli soldiers who were struggling with their role in the occupation.

Lauren Goldman Marshall, the playwright who spearheaded “Abraham’s Land,” said she intended for the play “to open up the dialogue.” (Lauren Goldman Marshall)

“I thought that there was an oppressor and an oppressed, and the Palestinians were living under a very harsh and brutal occupation,” Goldman Marshall told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

She wanted to help other Jews understand the effects of the occupation on the Palestinian people.

“I felt that maybe now Jewish Americans could hear this,” she said. “We needed to open up the dialogue. If we don’t speak out, who will?”

In the show, an Israeli soldier named Yitzhak kills a man named Ismail, a Palestinian with a bright future and a passion for coexistence, during a peaceful protest. Haunted by Ismail’s ghost, Yitzhak goes on a journey of self-discovery in an attempt to cope with the effects of his actions. Dressing as a Palestinian, he sneaks into Gaza and meets Ismail’s family in an attempt to seek their forgiveness.

Goldman Marshall worked alongside Eady and began to workshop the play with Jewish and Palestinian participants. First staged in 1991, the finished production reflected the kind of dialogue-driven optimism that defined the years leading up to the Oslo Accords. If the audience could just “see the humanity of the other side,” Goldman Marshall thought, perhaps it would inspire meaningful progress toward peace.

In 1999, Goldman Marshall reworked the play in collaboration with campers at Seeds of Peace, a nonprofit that brings together American, Israeli and Arab youth for peace-building summer camp sessions. At the camp, some of the adult chaperones from the Seeds of Peace Israeli delegation thought the play was “too pro-Palestinian.” After uproar from the students who were involved, the play was ultimately performed, but after that brief restaging, Goldman Marshall shelved the script.

Over the last few years, the playwright watched as conversations around the Israeli-Palestinian conflict shifted. American Jews as a whole grew more critical of Israel’s actions against the Palestinians, becoming increasingly comfortable with using words like “apartheid” to describe the country’s policies in Gaza and the West Bank. If the mainstream Jewish community wasn’t ready for the play when it came out in the 1990s, Goldman Marshall thought, perhaps they’d be ready for it now.

Goldman Marshall’s own views shifted, as well, to the point where she began questioning the entire Zionist project and the two-state solution.

“It is in Jewish best interests, morally and pragmatically, to rethink the notion of Israel as a Jewish state,” she wrote in a 2018 op-ed for The Seattle Times after the Trump administration moved its embassy in Israel to Jerusalem, a relocation that prompted protests from Palestinians and liberal Jews alike.

So while she saw an opportunity in this new climate to finally have a receptive audience for “Abraham’s Land,” Goldman Marshall also knew that the play would need to be adjusted to account for her own changing politics.

She began working with Eady on updating the script. The play had originally focused on both Yitzhak and Ismail as flawed characters in need of empathy for the other. But in its newer form, Ismail understands the Israeli experience, while Yitzhak struggles to come to terms with his role as an occupier.

When Eady saw these changes, he pushed back, telling Goldman Marshall that her script was insulting to the Palestinian cause. In particular, he objected to Goldman Marshall’s decision to make one of the Palestinian characters a suicide bomber — a portrayal Eady says is both racist and “harmful to a lot of Palestinians.” After months of disagreements, Eady ultimately pulled out of the project.

“It’s a real bad play — from the title to the last word,” he said.

Eady, who is still credited on the revival’s poster as an original co-writer, said he only got involved in the first place because, in the post-Oslo years, it felt like Goldman Marshall’s “both sides” approach was as good as things could get for Palestinians. He said he had objected to the treatment of the Palestinian characters at the time, but thought the play was his only chance to offer his side of the story.

“It was like taking [a] bucket of shit for a little bit of honey on the bottom,” he said.

The more recent groundswell of support for the Palestinian cause, both within the Jewish community and outside of it, emboldened Eady to demand more from the play this time around. He said his onetime collaborator refused to acquiesce.

Goldman Marshall said she remains committed to the idea that understanding the other — a framework that has fallen out of favor among many on the left who argue that it shores up an oppressive status quo — is the best way to achieve peace.

“I felt that if I could dig deeper, make the characters more three-dimensional, and broaden my own compassion, maybe I could move more hearts and minds,” she said.

After leaving the play, Eady soon found out that he was not alone in his frustrations with the play and its author. A number of other Palestinians who had participated in or advised on the show’s revival said Goldman Marshall had ignored their concerns over the portrayal of Palestinians in “Abraham’s Land,” or exploited their labor and experiences for her own goals.

The breaking point for many of the Palestinian participants was Goldman Marshall’s decision to cast Netanel Bellaishe, a Jewish Israeli actor, as Ismail, the Palestinian lead whose ghost haunts the Israeli character. Since the George Floyd protests last summer, Broadway has been embroiled in an ongoing debate about the limits of representation in theater, and actors and directors have questioned whether roles should be cast based on the race of the character, especially if those characters belong to an underrepresented community.

Bobbi Ktula, Hersh Powers, Lila Bahng, Hugh MacDonald and Mira Gross-Keck in the stage musical “Abraham’s Land.” (Ben Kerns)

The Palestinian participants who left the play wrote a letter, which JTA reviewed, to Goldman Marshall outlining their complaints. To them, it was unthinkable to cast Bellaishe, a former IDF soldier, as a Palestinian killed by an Israeli. Eady compares Goldman Marshall’s decision to a playwright deciding to cast a German to play a Jew in a play about the Holocaust.

The anger over casting Bellaishe wasn’t just about representation, they said — it was about the underlying politics of that decision. If Goldman Marshall was willing to cast an Israeli as a Palestinian, against the wishes of her own Palestinian crew members, did she actually care about their cause?

The producers of “Abraham’s Land” defended their decision to cast Bellaishe as Ismail, saying that he was the most qualified actor for the role, and highlighting the inclusion of Palestinian cast members elsewhere in the production.

“As far as I was concerned, there was no reason to not offer the role to Netanel, because he was quite clearly the best professional for the role,” said David Grabarkewitz, the play’s director.

Goldman Marshall says that while representation is important, actors also benefit from playing characters with different backgrounds than their own.

“I did feel very strongly that it was important to have Palestinian representation in the cast,” she says. “But I don’t think that it means that you always have to play your own side.”

But for Eady and the other Palestinians who left the project, Goldman Marshall’s words didn’t align with her actions. Falastiniyat, a feminist Palestinian activist group in Seattle, wrote a letter to Goldman Marshall on behalf of the Palestinian participants. In it, they claim that “when Palestinians expressed concern with the racism of the narrative, this feedback was ignored or outright justified.”

Palestinian cast members also said that Goldman Marshall routinely asked them to go beyond their role as actors and offer advice on Palestinian culture. While it’s normal for playwrights to solicit suggestions from their cast, the Palestinian participants claim Goldman Marshall effectively turned them into unpaid cultural consultants. Many of these crew members say they were also asked to share personal stories of their lives under occupation, which Goldman Marshall “edited without consent” by using them in ways that betrayed the original stories without consultation, according to the letter from Falastiniyat.

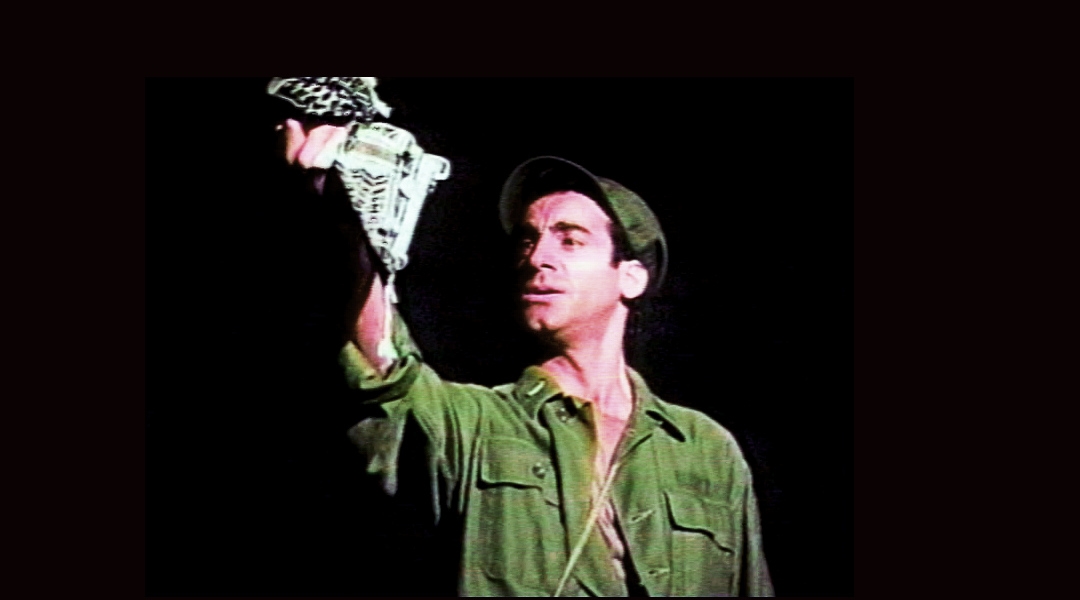

An early Seattle production of “Abraham’s Land,” starring Vincent Mancuso as Yitzhak, dates back to 1992. The show has undergone revisions since then, but its Palestinian collaborators still said the new version retained anti-Palestinian sentiments. (Lauren Goldman Marshall)

In a follow-up email, Goldman Marshall said that Falastiniyat had not provided evidence to support their claims, which she said were “either false or taken out of context.”

After Falastiniyat published its letter, Kadima withdrew its support for the project. The Reconstructionist synagogue initially published a message on its website explaining its decision, but has since removed it; the congregation told JTA it was revising its public message about the project, but did not provide the text of the original message. Various other interfaith organizations remain involved with the project.

In the end, many of the Palestinian actors who participated in the readings ended up quitting the production, feeling tokenized and ignored. Whereas Goldman Marshall believed she was facilitating dialogue and asking tough questions about the conflict, the Palestinian participants say she took advantage of their experiences to legitimize the production.

“If her goal is to convert Jews who support occupation, that’s not how you do it,” Eady says.

Some Palestinian groups and individuals, including the Gaza-based nonprofit Palestine Charity Team and its manager Alaaeldin Ahmed M. Abusaker, remain listed as supporters of the play; one of its summer performances was accompanied by a talk from a Gaza resident and public health professional.

At the end of the show, the protagonist exclaims, “It’s not Israel. It’s not Palestine. It’s Abraham’s land.” For Palestinian participants who left the play, this line ignored their struggle for recognition in favor of Goldman Marshall’s nebulous concept of empathy. Their letter is emphatic: “The land is and will always be Palestine.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.