(JTA) — Desmond Tutu, the archbishop who identified closely with the historical suffering of the Jewish people in his forceful advocacy against apartheid in South Africa, died Sunday at age 90.

Tutu, the first Black archbishop of Cape Town, used his role as a church leader to bring religion into the fight against apartheid, South Africa’s repressive system of racial segregation. Advocating for nonviolence and, later, restorative justice, Tutu gained renown far beyond South Africa, earning a Nobel Peace Prize in 1984.

In the years preceding and during the negotiations to end apartheid in South Africa, Tutu frequently praised the many South African Jews who opposed the apartheid system and worked alongside Black South Africans to transition to an equitable system of governance. He often invoked the Holocaust, comparing the struggles of the Jews under Nazism to the struggles of Black South Africans under apartheid.

Want the news in your inbox? Sign up for JTA’s Daily Briefing.

SUBSCRIBE HERESpeaking to a gathering of British Jews in 1987, he spoke of that shared experience of exclusion and persecution.

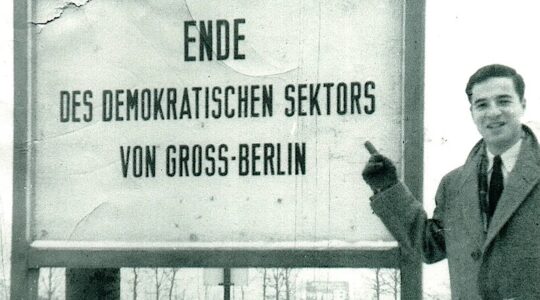

“Your people know what one’s talking about, having suffered because you belonged to a particular racial group. You were forced to wear arm bands. We don’t carry arm bands … they just have to look at us,” Tutu said, according to a Jewish Telegraphic Agency dispatch from the event.

Desmond Tutu during a visit to Jerusalem in December 1989. (Esaias Baitel/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images)

But Tutu’s identification with the Jewish people did not spare them from his criticism. While consistently defending Israel’s right to exist and calling on Arab nations to recognize Israel, including when speaking to Palestinian audiences, Tutu was a frequent critic of Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and questioned how people who had survived the Holocaust could perpetrate an occupation of another people.

“The Arabs should recognize Israel, but a lot must change also. I am myself sad that Israel, with the kind of history and traditions her people have experienced, should make refugees of others. It is totally inconsistent with who she is as a people,” he said in a 1984 speech at the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York.

Tutu also criticized Israel for continuing to work with South Africa on military matters despite apartheid.

“Israel’s integrity and existence must be guaranteed. But I cannot understand how a people with your history would have a state that would collaborate in military matters with South Africa and carry out policies that are a mirror image of some of the things from which your people suffered,” he said in his 1987 speech to British Jews.

Those comparisons, along with remarks that some Jewish leaders called antisemitic, earned Tutu criticism from some Jewish leaders. In his 1984 JTS speech, he addressed some of that criticism while further fanning its flames with references to a “Jewish lobby.”

“I was immediately accused of being antisemitic,” Tutu said in his speech, referring to the reaction to an earlier speech. “I am sad because I think that it is a sensitivity in this instance that comes from an arrogance — the arrogance of power because Jews are a powerful lobby in this land and all kinds of people woo their support.”

In a 1989 visit to Israel and the West Bank, Tutu made the controversial suggestion during a visit to Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust memorial, that the Nazis ought to be forgiven for their crimes against the Jewish people. The suggestion reflected Tutu’s role as the chair of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which aimed to move the country into a new era by allowing those who participated in apartheid to atone for their sins and to let victims of the system air their grievances and, in some cases, receive reparations.

“We pray for those who made it happen, forgive them and help us to forgive them, and help us so that we, in our turn, will not make others suffer,” he said, according to a JTA dispatch from the time.

Jewish leaders criticized Tutu for his remarks. “For anyone in Jerusalem, at Yad Vashem, to speak about forgiveness would be, in my view, a disturbing lack of sensitivity toward the Jewish victims and their survivors. I hope that was not the intention of Bishop Tutu,” Elie Wiesel said at the time.

Despite his comments, Tutu was frequently honored by Jewish organizations. In 1989, he was honored for his work fighting racial discrimination by the Stephen Wise Free Synagogue in New York. In 2003, Yeshiva University’s Cardozo Law School gave him an award for furthering world peace.

In 2009, the same year that then-President Barack Obama awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom, Tutu was disinvited from giving a speech at a Minnesota university over remarks he had made about Jews and Israel.

“Tutu has certainly been an outspoken, sometimes very harsh critic of Israel and Israeli policies, and has sometimes also used examples which may cross the line,” Foxman told JTA at the time. But Tutu “certainly is not an antisemite and should not be so characterized and therefore refused a platform.”

“If change seems impossible, consider our experience in South Africa,” he said. “You can make it happen in Palestine and Israel, too.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.