(JTA) — For most of the Shabbat services streamed from Congregation Beth Israel in Colleyville, Texas, over the course of the past two years, only a few dozen people ever tuned in, mostly from their homes in the Fort Worth suburb.

But as the regular Shabbat morning service led by Rabbi Charlie Cytron-Walker was transformed into a harrowing hostage situation Saturday, thousands of people tuned in from all over the world.

“How many people are in there?” one woman commented on the video as she watched, the strains of the attacker’s voice audible on the stream. “Prayers,” another person wrote, as heart and anger emoji “reactions” flowed alongside the video, which was frozen on an empty stage.

Another comment summed it up: “OMG. Is this LIVE??”

It was — and it remained that way for a significant amount of time before being taken offline, giving an unprecedented number of people got a front-row seat Saturday into a dangerous attack on a Jewish community.

The dynamic was very different from past synagogue attacks, including the 2018 shooting at Tree of Life Congregation in Pittsburgh in which 11 Jews were killed during Shabbat services. There, news trickled out, but much remained unknown about what transpired inside the synagogue for some time.

Like Congregation Beth Israel, Tree of Life began streaming its services in 2020 after the COVID-19 pandemic made in-person prayer dangerous.

A gunman aimed to stream his attack on a synagogue in Poway, California, in 2019, inspired by the perpetrator of a mass killing at two mosques in New Zealand who streamed the violence on Facebook. But he was not successful.

In Colleyville, the streaming was not a promotional strategy by a violent attacker but a function of the synagogue’s technology. Congregation Beth Israel began streaming services in March 2020, shortly after shutting down because of the pandemic, and like many synagogues it eventually set up cameras that are permanently trained on the bimah, where they remained focused on Saturday after the hostage situation began.

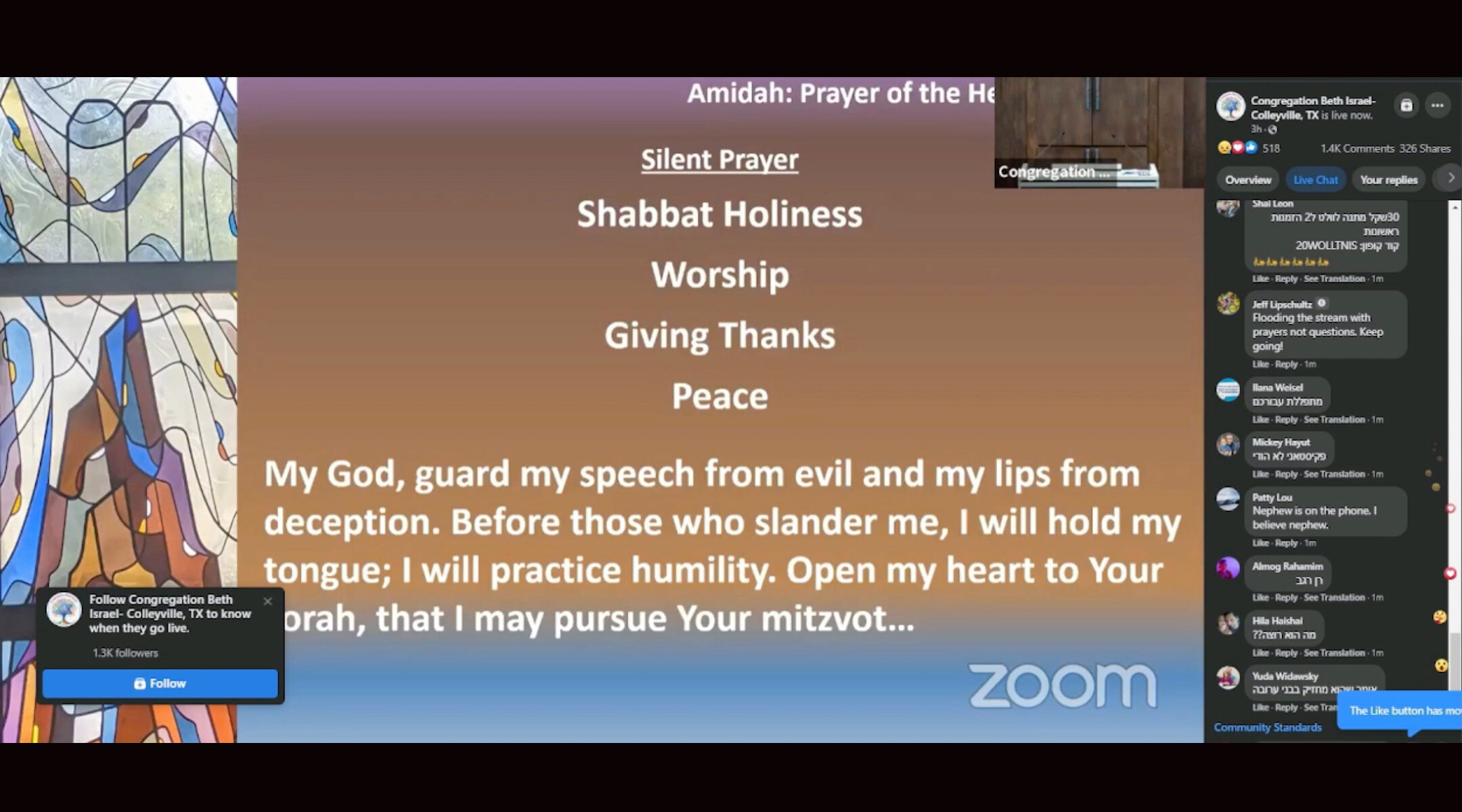

All over the world, thousands of people listened as the disembodied voice of the armed attacker came through their computers. Their screens showed the silent prayer that ends the Amidah, the point in the service at which the attacker interrupted the prayers.

Those listening in included law enforcement representatives who benefited from being able to hear what was happening inside the synagogue and people close to the congregation who tuned in to see if people they know and care about were safe.

It likely also included people who had never heard of Colleyville before Saturday and people who may have never set foot in a synagogue before.

The attack’s transparency could be especially significant for them, Amy Asin, the vice president and director of Strengthening Congregations at the Union for Reform Judaism, told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

“Most non-Jews don’t realize that Jews cannot worship free from fear,” said Asin, who works with Reform congregations such as Congregation Beth Israel on issues relating to security. “If this helps people understand that I’ll take it as a benefit.”

The fact that Beth Israel’s service was streaming likely changed the dynamics of the experience for the hostages, as well. The recent rise of the omicron variant meant that fewer people than usual were inside on Saturday morning; most of the people who participated in the service did so from home. Only four hostages, including Cytron-Walker, were taken, and the streamed audio made clear that he and others had built a relationship with the attacker.

“We have to remember,” Asin said, “that even if the sanctuary is empty of worshippers, the service leaders are still there and we have to provide security for them.”

Some time into the crisis, the livestream was taken down, causing community members who had been watching with concern to be plunged into darkness.

“The live stream got shut down and I have no idea what’s happening anymore,” tweeted Ellen Smith, a congregant who commented widely during the crisis Saturday.

Michael Masters, the national director and CEO of the Secure Community Network, which works to boost security in synagogues and other Jewish institutions, said the situation points to a core challenge as Jewish communities adapt to more pervasive streaming.

“What’s important is that there is a plan in place by the individual synagogues or institutions for managing those streams in live feeds,” Masters said. “So that if an incident does occur, or an event does occur, those can be accessed remotely or on site and shut off either remotely or on site.”

At the same time, he said, streaming can help law enforcement understand what is happening inside a synagogue during an attack.

The streaming also allowed some inaccurate information to proliferate, such as the idea that the attacker was the biological brother of the woman he hoped to free from imprisonment. In fact, he had called her “sister” as an expression of solidarity.

That’s all part and parcel of the streaming of Jewish communal life, which accelerated because of the pandemic but should be understood as a permanent shift, according to Lex Rofeberg, senior Jewish educator at Judaism Unbound.

“There are dangers in livestreams being so accessible in moments of intensity. There are also really positive pieces,” Rofeberg said.

“There’s a way in which livestreaming breaks open our ideas about geography,” he added. “When I can go on Facebook Live or Youtube Live or synagogue websites, that creates a new form of transgeographical connection that is powerful — and unfortunately adds to some of the pain in a moment like this.”

Though the livestream offered limited information about what was happening inside the synagogue, the last two years of streaming at Congregation Beth Israel generated much more detail.

Watching videos of previous services, viewers can see that Cytron-Walker, a transplant from Michigan, has become a real Texan since becoming Beth Israel’s rabbi in 2006 and frequently slips “y’all” into his speech. They can see that Cytron-Walker likes to intersperse his live streamed services with videos of cantors and choirs from around the world singing some of the prayers in the service. And they can see firsthand evidence that Cytron-Walker may be, as Smith lovingly identified him in a Zoom vigil on Saturday, the “worst singer in the world.”

Strangers could even see what Cytron-Walker was planning to teach in a Torah study session Saturday; his lesson plan for the day was posted to Sefaria, an online database of Jewish texts. In it, Cytron-Walker planned to talk about the sense of uncertainty and stress felt by many during the pandemic. He planned to finish with a comment from Moshe Greenberg, an influential 20th-century Bible scholar, on the verse from Exodus 7:3, “I will harden Pharaoh’s heart.”

That comment had resonance for the situation that Cytron-Walker found himself in during services. “While events unfold under the providence of God,” Greenberg wrote, “their unfolding is always according to the motives of the human beings through whom God’s will is done without realizing it.”

In the wake of the incident, Asin said she was heartened by the supportive response from across and beyond the Jewish community. She also said she didn’t think that the unprecedented transparency of the latest assault on American Jews would change the shape of antisemitism in the country.

“I’m personally hopeful — and skeptical that the public nature of this event will have any impact,” she said.

Ron Kampeas contributed reporting.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.