JERUSALEM (JTA) – Among the antiquities that billionaire philanthropist Michael Steinhardt is accused of trading illegally is a 2,200-year-old artifact that was likely looted from a cave complex regularly excavated by young Jews traveling to Israel on a program that Steinhardt funds.

The ties among the Heliodorus Stele, Birthright Israel and Steinhardt illuminate just how complicated a relationship Israel has with the philanthropist, who is widely known there as a generous champion of arts and culture.

Prosecutors in New York have condemned Steinhardt’s “rapacious appetite for plundered artifacts,” exacting from him last month a promise never again to trade in items produced more than 600 years ago. He also agreed to surrender 180 looted antiquities worth some $70 million, including 40 that came from Israel and the West Bank.

But in Israel, where Steinhardt’s name appears in the name of a major museum and on the walls of several cultural institutions, responses to the unprecedented deal have been muted, if they have come at all.

“Mr. Steinhardt is a valued supporter and a longtime friend of the Israel Museum and his lifelong involvement is genuinely appreciated,” the Israel Museum said in a statement.

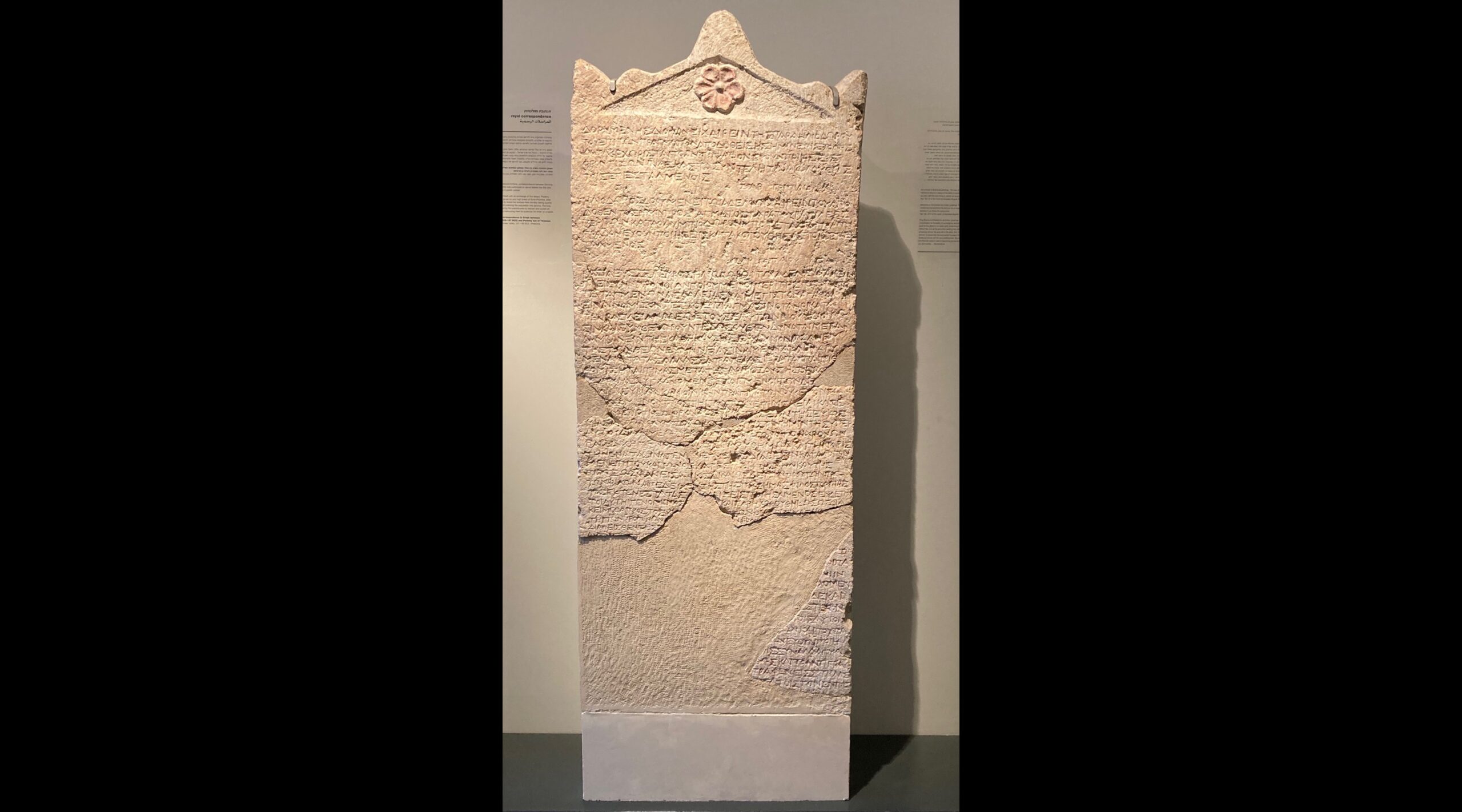

The Heliodorus Stele, on display at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, is among the 180 looted antiquities that Michael Steinhardt has agreed to surrender in a deal with the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office. (Asaf Shalev)

The museum, Israel’s premier showcase for art, received the Heliodorus Stele from Steinhardt on a long-term loan and it remains there on display. Etched in Greek on a limestone slab, the stele testifies to the period leading up to the Maccabean Revolt, an event memorialized every year by Jews during Hanukkah.

The stele was completely unknown to scholars in 2006 when Steinhardt bought it from an antiquities dealer named Gil Chaya. Chaya maintains that the item was purchased legally from a private Palestinian collection formed decades earlier, before laws about looting applied. According to the Manhattan District Attorney’s office, Chaya has trafficked in illegal antiquities and he is under criminal investigation.

At the time, Steinhardt may have had no reason to believe the stele was looted. Chaya was operating a license from the Israel Antiquities Authority, which enforces laws on archeological commerce and research. The stele itself had been studied by at least three university professors.

Most importantly, the antiquities authority was aware of the artifact, having inspected it and reviewed Chaya’s claims about its origin, according to interviews with one of the professors as well as with Chaya and his former wife, who was also his business partner.

“I told Chaya I wouldn’t read it before he declared it to the Israel Antiquities Authority,” said one of the professors, Hannah Cotton of Hebrew University, who said she was initially doubtful of the artifact’s legality. “And he did declare it.”

Yet the provenance question resurfaced soon after the stele went on display. An archeologist named Dov Gera noticed that the slab’s broken bottom edge fit perfectly with two fragments found a year earlier during an official excavation at an archaeological site called Tel Maresha in central Israel. That discovery suggested that Steinhardt’s slab had been looted at some point from the cave where the fragments were found.

Indeed, in 2005, when archeologist Ian Stern brought groups of tourists to volunteer as excavators in the cave, part of what’s known as Subterranean Complex 57, he noticed signs of looting. Vandals had snuck in and plundered the caves, enlarging a passageway between two chambers and leaving debris behind, Stern recalled in an interview.

Many of the volunteers at Tel Maresha are first-time visitors to Israel spending the day digging as part of their Birthright Israel trips — a program founded and partly funded by Steinhardt with the goal of strengthening Jewish identity for Diaspora Jews. More than mere tourists, these crowds arriving with Stern’s Dig for a Day program supplied free labor and generated revenue for the official excavation. It was a volunteer group, by chance, not Birthright-affiliated, that found the stele’s fragments.

Stern was distressed by the looting at the site, which he said happens regularly and is all but impossible to stop. But he said he harbored no resentment of Steinhardt, despite extensive allegations made against him for trading in looted relics.

“Here’s kind of a strange thing for me to say as an archaeologist,” Stern said. “I’m actually pleased that it was purchased and put on loan in the museum. In other words, the alternative of some antiquity collector putting it in the basement of his home would have been tragic. Scholars were able to actually analyze it and write about it.”

Beneficiaries of Steinhardt’s largesse have been looking for silver linings in his giving since 2019. That was when his life’s narrative — hedge fund manager who made his fortune, quit the business and decided to devote his life to the Jewish people — cracked after several women came forward to accuse Steinhardt of sexual harassment, painting an alleged pattern of inappropriate sexual advances in professional settings and hurtful comments.

At the time, Lila Corwin Berman, a professor of history and director of the Feinstein Center for American Jewish History at Temple University, wrote, “A clear line connects Steinhardt’s philanthropic power and a long-standing pattern of tolerance by the Jewish community of his alleged conduct toward women and their bodies. The power he wields, and the belief among many Jewish organizations and their leaders that he was too powerful to rebuke, is the result of a historical shift that has seen many Jewish communal structures becoming beholden to megadonors.”

By the time of the sexual harassment expose, Steinhardt had been served at least two of an eventual 17 search warrants for the seizing of antiquities, documents, computers and other devices from his home and office.

In December, the deal Steinhardt made to avoid prosecution was announced and a report filed with a New York court detailed Steinhardt’s alleged pattern of criminality. The evidence against him includes an alleged admission by Steinhardt that he has no regard for where artifacts come from.

“You see this piece?” Steinhardt reportedly said to an FBI agent while pointing to an artifact in his possession. “There’s no provenance for it. I see a piece and I like it, then I buy it.”

The investigation also yielded emails to Steinhardt and his representatives from well-known antiquities traffickers detailing illicit excavations, botched restorations and the accidental loss of parts of artifacts by “peasants” hired as looters.

Among the 40 looted artifacts from Israel and the Palestinian territories were the stele; a set of 9,000-year-old stone masks from the Judean desert said to be the oldest masks in the world; Bronze Age figurines carved out of ivory; and amulets, an incense burner and a cosmetic spoon.

Museum donors Michael Steinhardt and Judy Steinhardt pose with museum director James Snyder at a fundraiser for the Israel Museum in New York City, Oct. 25, 2010. (Clint Spaulding/Patrick McMullan via Getty Images)

Then-Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance announced the investigation in a press release that decried Steinhardt harshly. Steinhardt, Vance said, was responsible for “grievous cultural damage he wrought across the globe.”

That tone went unmatched in Israel. A single columnist at Haaretz, followed by an editorial from the newspaper, argued that the billionaire’s name should be stripped from the Steinhardt Museum of Natural History in Tel Aviv.

The pushback was switft and adamant. In a letter to the newspaper, Zalman Shoval, a veteran political figure, accused the Haaretz columnist of engaging in “cancel culture” and suggested that whatever wrong Steinhardt might have done pales in comparison with his contributions to Israel.

Another letter, from Martin Weyl, who served as the director of the Israel Museum from 1981 to 1996, also defended Steinhardt, arguing that other collectors making donations to museums have behaved far worse than Steinhardt. Citing the lack of an indictment, Weyl suggested that prosecutors were seeking publicity rather than justice.

The decision to investigate Steinhardt and the various reactions to the allegations against him must be seen in the context of the changing norms around cultural heritage, said Raz Samira, who chairs Israel’s Association of Museums and represents the country on the International Council of Museums.

“It’s a revolution of the past few years,” Samira said. “Museums have many collections that were donated by private individuals. Most of this stuff was taken in one way or another. Today when you are offered an item and you don’t have provenance for it, you think three times before you do it. That wasn’t the case three to four years ago.”

According to Patty Gerstenblith, a law professor and director of DePaul University’s Center for Art, Museum & Cultural Heritage Law, however, Steinhardt’s status in Israel has long been insulated from political headwinds.

“It is more difficult to understand the detriment that is done to science and to history and heritage through looting, a somewhat abstract concept, than to understand the more immediate and tangible benefit that comes to some through philanthropic donations,” Gerstenblith said.

Through a representative, Steinhardt declined to be interviewed, asking instead for written questions to which he never responded. He did not admit to any crimes in his deal with the Manhattan District Attorney’s office. His lawyers have suggested in statements to the media that Steinhardt had bought looted antiquities because he had been repeatedly deceived by dealers providing false information about the provenance — or history of ownership — of what they were selling. He stands accused of having bought 1,000 plundered artifacts since 1987.

Israel’s antiquities authority, the IAA, which is credited by the New York prosecutors with assisting the investigation, declined to comment. And the Israel Museum, too, declined to make employees available for interviews for this article or answer any specific questions about the terms under which Steinhardt loaned the stele and other items to the museum and how the museum’s treatment of provenance has evolved over the years.

A spokesperson said that only a director could address questions relating to major donors and that the museum was without one at the moment.

A new director, Denis Weil, is set to assume the role in March; he has never led a museum before. He replaces Ido Bruno, who stepped down last May after four years at the museum’s helm. Bruno followed James Snyder, who led the institution for two decades, including at the time it acquired the Heliodorus Stele and several other objects from Steinhardt.

Snyder commented in 2002 at the annual gala of the Israel Museum that he owed his position to long-time donors Steinhardt and his wife Judy, according to a column in The Jerusalem Post.

“Six years ago, [Snyder] disclosed, Judy Steinhardt, whom he did not know at the time, called him to propose the idea of going to Israel,” the newspaper reported. It went on, “The rest is history.”

Ella Rockart contributed reporting to this story.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.