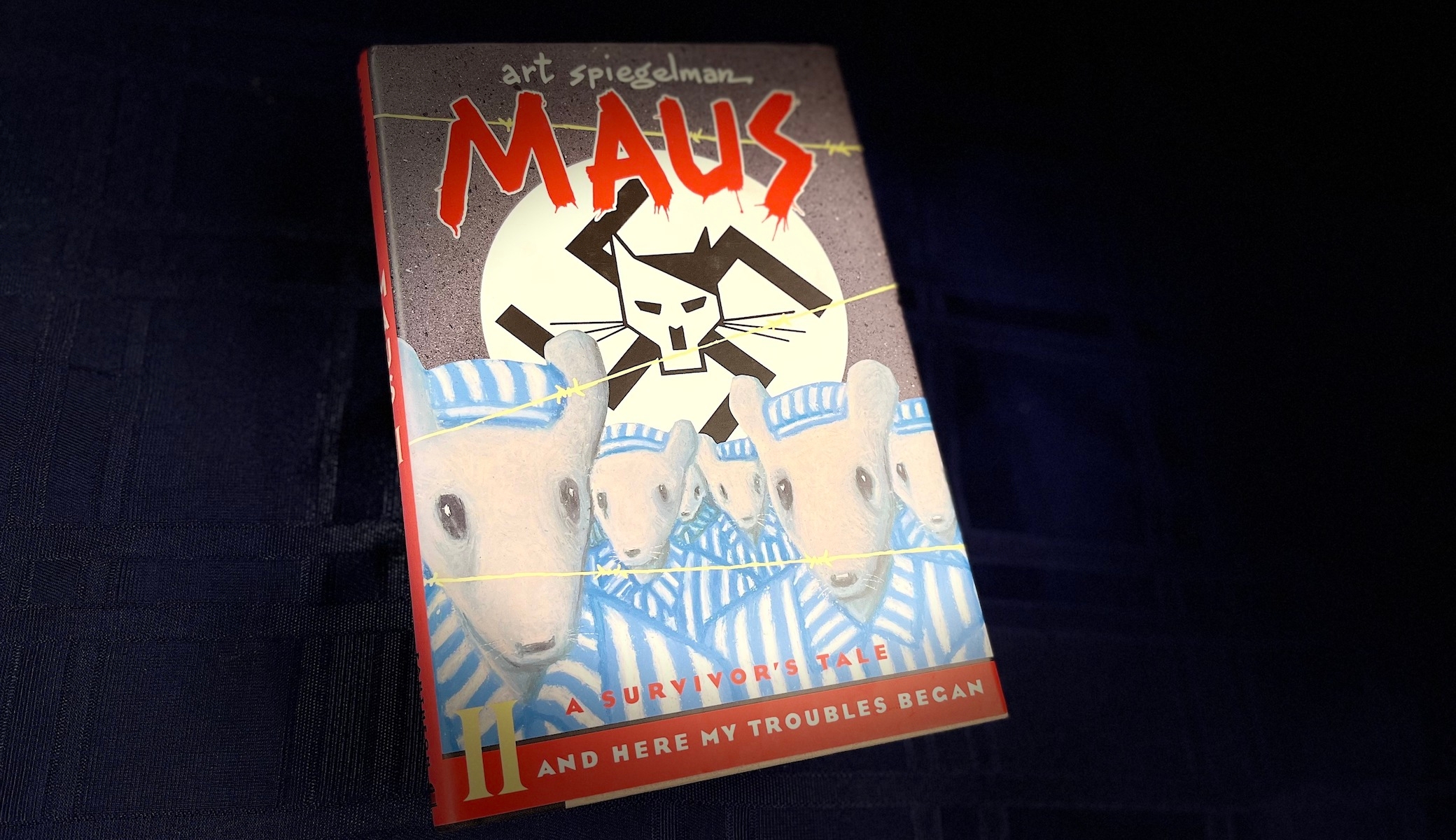

(JTA) — Art Spiegelman once complained that “Maus,” his classic memoir about his father’s experiences in the Holocaust, was assumed to be intended for young adults because it took the form of a comic book.

“I have since comes to terms with the fact that comics are an incredible democratic medium,” he told an interviewer.

“Adults” seemed to agree: “Maus” won a Pulitzer Prize citation and an American Book Award and remains 36 years after its first appearance in hardcover one of the most searing accounts ever written of the Shoah and its impact on the children of survivors.

I remembered Spiegelman’s concern after a Tennessee school board voted last month to remove “Maus” from middle-school classrooms, citing its use of profanity, nudity and depictions of “killing kids.” The reaction to the ban from outside McMinn County was swift and angry. Booksellers offered to give copies away. A professor offered local students a free online course about the book. Sales soared. The fantasy writer and graphic novelist Neil Gaiman tweeted, “There’s only one kind of people who would vote to ban Maus, whatever they are calling themselves these days.”

But the debate over “Maus” has in many ways done a disservice to Spiegelman and his epic project. Because to read some of the comments from defenders of the book, you’d think “Maus” is a challenging but ultimately tween-friendly introduction to the horrors of the Nazi years — a sort of Shoah textbook with mouse illustrations.

However, “Maus” is not, as Spiegelman once pointed out, “Auschwitz for Beginners.” It is not — or not just — a book about “man’s inhumanity to man,” the phrase that actor Whoopi Goldberg got in trouble for using to explain the Holocaust. It is infinitely wilder and woolier and more unsettling than that. It is about the complex relationship between a father who has experienced the worst a person can experience, and a son raised in relative middle-class comfort. It is about mental illness and how a mother’s suicide haunts the child who survives her. It is about guilt in many forms, and how it can be transmitted through generations.

I hadn’t looked at a copy of the book in years before the current controversy, yet I could still recount by memory its opening almost frame by frame. A 10- or 11-year-old Artie is playing with friends in his neighborhood in Queens, when they abandon him on the way to the playground. Artie comes home to find his father Vladek in their driveway and explains through tears that his friends had skated away without him.

“Friends? Your friends…,” says Vladek. “If you lock them together in a room with no food for a week… THEN you could see what it is, friends!”

With this little slice of childhood trauma, we are suddenly deep into the world of “Maus,” where, as the first chapter proclaims, Vladek Spiegelman “bleeds history.” Art Spiegelman does not deliver saintly characters oppressed by cartoon villains. His father, like his son, is deeply human and anguished, buffeted by his time in the camps and his wife’s suicide and consumed by his own ingrained if understandable prejudices.

At one point in the second volume, Vladek complains to Spiegelman and his wife about the “coloreds” who he says used to steal from their co-workers in the Garment District. It’s an unflattering version of his survivor father that Spiegelman could easily have left out of the book, but there is nothing easy about “Maus.”

This week a writer asked me to consider publishing his essay about “Maus,” in which he objects to the portrayal of Vladek’s miserliness, both Spiegelmans’ “narcissism” and the books’ examples of “Jewish self-loathing.”

He’s not wrong, exactly. But the triumph and tragedy of “Maus” is its veracity – a commitment to the facts of Auschwitz matched by its honesty about the complexities and ambiguities of its victims and survivors. In an interview for the book “MetaMaus,” Spiegelman explains that his book “seems to have found itself useful to other people in my situation, meaning children of survivors. … The mere idea of a child of survivors resenting and resisting his parents was breaking a taboo that I hadn’t expected.”

I for one don’t see the harm in exposing children to books that may be beyond their years. And given the flood of content that comes the way of any child with a cell phone, laptop or television set, I find the idea of “protecting” kids from violent and sexual imagery in the name of education incredibly quaint.

But let’s not pretend that “Maus” is ready-made for the teen market. “Maus” is “adult” not because of its depiction of corpses, its nudity and the acknowledgment that people have sex. It is adult in that it refuses to sugarcoat not just the horrors of the Holocaust, but the personalities of its victims.

It is not, in short, a book I’d give to a tween without hoping to discuss it, before and after — to help them understand not only what they might not understand, but to confront the things that none of us understands.

In short, it is a book that should be taught, and taught well.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.