(JTA) – When the U.S. government announced that it would seek to seize the assets of VEB, Russia’s main development bank, a lawyer for the Chabad Hasidic movement was thrilled.

For years, Chabad has sought a collection of sacred texts and documents that were taken from the movement after the Russian Revolution and during the Holocaust, and ended up in the hands of the Kremlin.

And for years, the United States had opposed Chabad’s efforts to seize Russian assets as a bargaining chip in their quest.

Now, the United States is going after the very same funds, establishing a legal connection between VEB’s assets and the Russian government.

“The federal government determined that VEB is a piggy bank for the Kremlin, it’s essentially a tool of the Russian state,” said Steven Lieberman, an attorney who is representing Chabad pro-bono.

In hunting for Russian assets to seize amid an effort to sanction Russia for invading Ukraine, the White House is to some degree following in Chabad’s footsteps. The saga began in 2004 when Chabad-Lubavitch, the Brooklyn-based Hasidic movement, filed a lawsuit in U.S. federal court to demand that Russia return the texts.

Never miss a story. Sign up for JTA's Daily Briefing.

SUBSCRIBE HEREThe court ruled in Chabad’s favor and — after Russia failed to comply — imposed a fine of $50,000 a day on the country. Today, Russia owes Chabad more than $165 million. Subsequent court orders have authorized Chabad to claim certain Russian assets in the amount of the fine.

But claiming those assets requires finding them first. Because so much of Russian wealth is tied up in ostensibly private companies, not the state, that can be tricky. It requires a legal process of subpoena-writing that attorney Nicholas O’Donnell, who specializes in lawsuits against foreign governments over property such as Nazi-looted art, compares to a game of whack-a-mole.

“It’s hard especially in this case because the foreign sovereign, Russia, is acting in bad faith,” he said. “They are hiding assets to avoid paying the money that they owe.”

Chabad says it would prefer ownership of the collection to seeing fines continue to accrue. Known as the Schneersohn library and archive, a historic collection of 12,000 books and 50,000 documents named for Rabbi Joseph I. Schneersohn, who led the movement until his death in 1950. It is considered of particular sentimental value because it was amassed over 200 years and then stolen by government authorities bent on persecuting the Chabad movement and Jews in general.

Part of the collection is made from a library that was nationalized by Soviet authorities in 1920. The other part is made up of the books and documents Chabad collected in the ensuing years as the movement resettled in Latvia and then in Poland. This second collection was looted by Nazis during World War II and then by the Red Army.

“Our hope is that if we can seize those assets, it will put enough pressure on Putin and his minions that they will finally decide to return to this library of holy books, which means so much to Jews throughout the world, but which means nothing to the Russian government,” Lieberman said.

Years before Russia invaded Ukraine and the Biden administration decided to capture Russian wealth held in the United States, Chabad’s lawyers were busy tracking down that wealth. They issued subpoenas to numerous financial institutions and companies seeking relevant information.

By late 2021, two entities had emerged as Chabad’s primary targets: Russia’s main development bank, VEB, and Tenex, a subsidiary of a Russian state-run company called Rosatom that sells uranium to nuclear power plants in the United States.

The United States announced sanctions on VEB on Feb. 22 in the lead-up to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, freezing the bank’s U.S. assets. Its determination that VEB is effectively state wealth has given Lieberman confidence that Chabad can eventually convince the U.S. Treasury Department to turn over VEB assets.

“Treasury from time to time grants what are called OFAC licenses where they essentially give third parties the rights to assets they’ve seized,” he said. “They’ve done that, for example, in certain terrorism cases.”

Not everyone is sure things will play out so favorably for Chabad. O’Donnell, who has been following the Chabad case but not working on it, said it’s likely the United States would resist claims on the seized assets.

“I’m not sure the U.S. government wants to create a situation where they seize a whole bunch of money, and then a whole bunch of other people who claim to have been wronged by Russia — which is a very, very long list — say they should be getting some or all of the money,” he said.

If VEB’s U.S. assets are all tied up in sanctions, Tenex remains entirely unrestricted. That’s because when the Biden administration imposed sanctions on Russia’s energy industry on March 8, it exempted nuclear power, allowing the continued import of Russian uranium.

“If we’re allowed to seize the assets of Tenex, Chabad will be the only religious organization in the world that has its own nuclear power supply,” Lieberman said, half-jokingly.

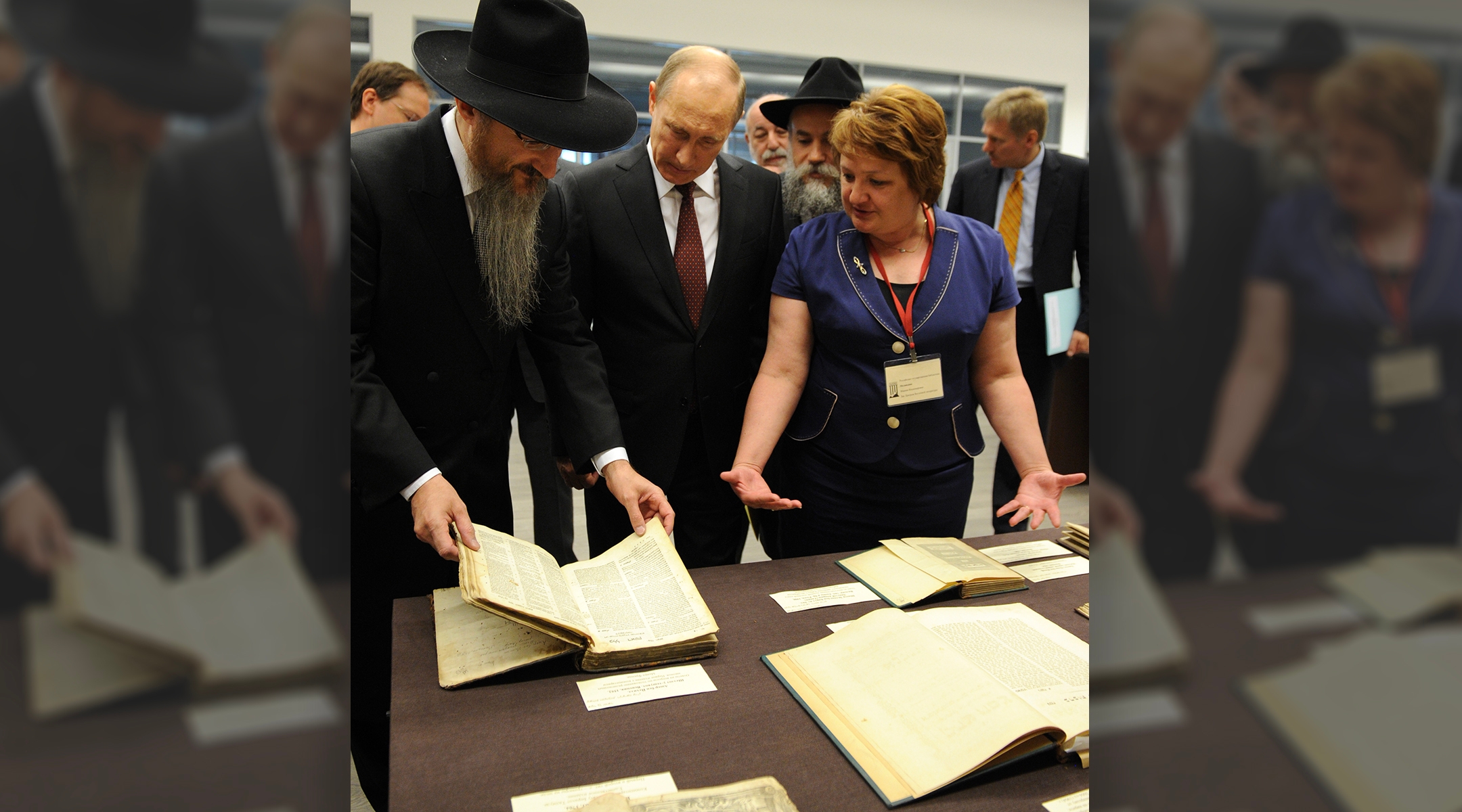

Putin and Lazar examine items in the Schneersohn library at a Chabad-run museum in Moscow, June 13, 2013. Chabad seeks ownership of the entire collection. (YURI KADOBNOV/AFP via Getty Images)

Ironically, the U.S. government has long opposed Chabad’s legal efforts against Russia, arguing that the group’s attempts to seize Russian assets would undermine diplomatic aims. In 2016, for example, the U.S. Department of Justice argued in a court filing that seizing assets “could cause significant harm to the foreign policy interests of the United States.”

O’Donnell said the policy of the United States is to oppose civil claims against foreign governments.

“The United States will almost always take the side of a foreign sovereign no matter how regressive or repressive,” he said. “They will do it for Saudi Arabia, they will do it for Iran. It’s actually sort of shocking.”

Lieberman declined to answer questions about whether Chabad has been in touch with the U.S. government about the issue, but he noted that there have been no court filings opposing its motions targeting VEB and Tenex.

“The State Department has now come over to our side,” he said, citing the government’s publicly stated position on Russia. “It’s very clear that the US government’s interest is 100% in applying sanctions and seizures to assets of the Russian Federation. So finally after 20 years, we’re getting full support from the U.S. government.”

In its defense, the Russian government has said it considers the Jewish texts a “treasure of the Russian people.” Some of the collection is held by the Russian State Library and the Russian State Military Archive.

Russian President Vladimir Putin tried to put the dispute to rest in 2013 by transferring some of the collection to Moscow’s newly established Jewish Museum and Tolerance Center, which is affiliated with Chabad and headed by Russia Chief Rabbi Berel Lazer, a Chabad rabbi.

Lazar’s spokesperson spoke to JTA about the dispute at the time.

“Putin’s suggestion came as a surprise to us, and not a very pleasant one,” Gorin said. “We very much wanted to stay out of the dispute,” but “when the president of Russia makes a suggestion, it is usually accepted.”

Ultimately, Putin’s move did nothing to diminish the resolve of Chabad’s Brooklyn headquarters, Agudas Chasidei Chabad, which kept pursuing the matter in court — meaning that Chabad is in effect suing to claim property that’s on display at a museum that the movement itself runs.

Ownership is what’s at stake, according to Lieberman.

“The books are under the control of the Russian government. If Chabad wanted to come and take the books and bring them back to 770 Eastern Parkway, the answer is no,” he said, referring to the address of the group’s headquarters in Brooklyn.

If Chabad’s ability to operate in countries that are at odds with one another at the same time was difficult before, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has only made things much trickier.

Court rulings that would enable the group to proceed are expected in the next few months.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.