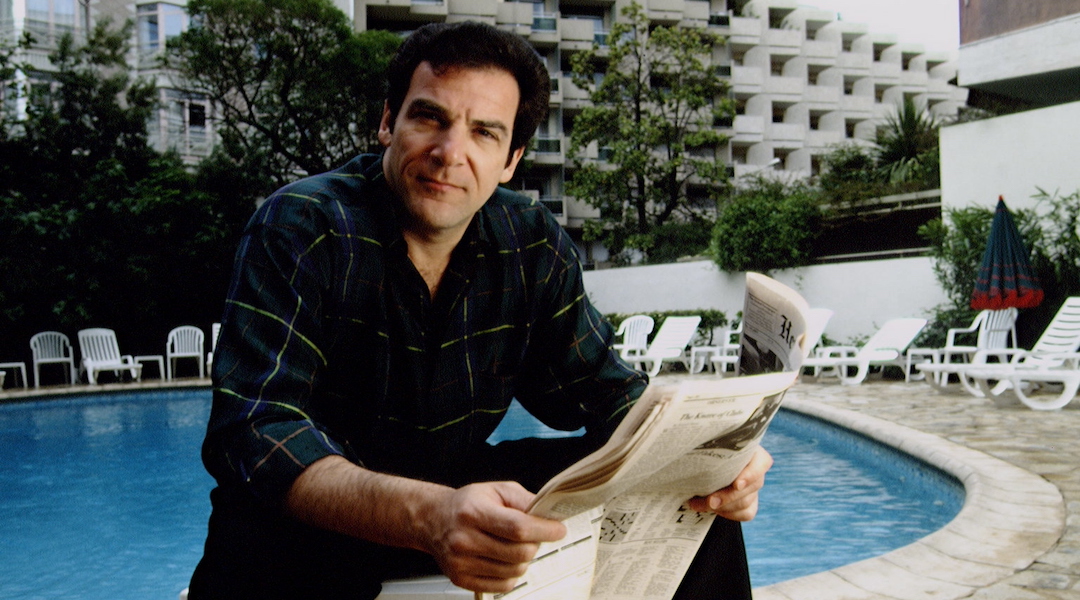

One Jewish celebrity missing from last week’s star- studded Hollywood tribute to Israel’s 50th birthday was Mandy Patinkin.

The quintessentially Jewish performer has a strong point of view when it comes to his Jewish life. In this case, it was politics that kept him away.

He declined an invitation to participate in the tribute, which was co-hosted by Kevin Costner and Michael Douglas, because he is deeply opposed to the current Israeli government’s attitudes toward the Middle East peace process.

“I would love to participate but I feel like my hands are tied,” he said of the show that aired April 15 on the CBS television network.

Sitting in his snug home office recently in the rambling Manhattan apartment he shares with his wife and two adolescent sons, Patinkin said of the stalled peace process: “It’s a tragedy, what’s happening. I pray with every ounce of my being that the peace process continues.

“It’s a symbol for the entire world, and if it’s not attended to, we’ll all have a heavy price to pay.”

Patinkin’s work is infused with the Jewish sensibility that characterizes his life.

His convoluted syntax and urban inflection when he spoke as Dr. Jeffrey Geiger on the television program “Chicago Hope” suggested that the character’s birthplace was a shtetl.

Then there was the movie “Yentl,” in which he played the yeshiva study partner of the “boy” played by Barbra Streisand.

Now the Tony-and Emmy-award-winning performer has come out with a Yiddish compact disc, on which he mixes classic Yiddish musical gems with unexpected American songs translated into the “Mamaloshen,” which is the name of the recording.

Patinkin heard shards of Yiddish from his grandparents as he was growing up on Chicago’s South Side. But to make the CD he had to learn it from the ground up.

Classics like “Oyfn Pripetshik” and “Raisins and Almonds” are interspersed with translated renditions of “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” and “White Christmas,” which was written by Irving Berlin, a Jew who never wrote a single lyric in his native Yiddish.

Mary Poppins’ song “Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious” is part of a medley that starts with the song “Ten Kopeks” and ends with “The Hokey Pokey.”

The project started eight years ago, when theater producer Joseph Papp asked his friend Patinkin to do a benefit for the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research.

At a Shabbat dinner at Patinkin’s home later, Papp told Patinkin that he had to make Yiddish music his own.

The comment from Papp, who was like a second father to Patinkin — he signed the ketubah at Patinkin’s wedding, and carried his first son at the traditional pidyon ha-ben ceremony when the baby was a month old — made a lasting impression.

“Then Joe dies and won’t let me out of it,” said Patinkin. “This promise I made to Joe began to loom in my face.”

So he got in touch with two modern masters of Yiddish, Henry Sapoznik and Moishe Rosenfeld, who gave him a box full of tapes and began to teach Patinkin the language of his ancestors.

It was, said Patinkin, an experience that captured his whole heart.

“His inflection, his pronunciation is so genuine that you would never believe this is something he just learned,” said Irving Skolnik, who was Patinkin’s Hebrew school principal in Chicago.

As a child Patinkin stood out — as a talented singer and, as he recalls it, something of a troublemaker who spent a lot of time in the principal’s office.

He was a soloist with the children’s choir at his Conservative congregation.

“The music, the holidays, junior congregation appealed to him because it involved davening,” or praying, Skolnik recalled. “That was the thing that really turned him on.”

As a teen-ager he went to Jewish camp. But in college, Patinkin said, he had “no Jewish life” at the University of Kansas.

“My Judaism came back to me in a rush when I met my wife,” he said, referring to Kathryn Grody, an author and actress.

“When I met her I just loved her, and that had never happened before. My feelings were so full. I started saying the Shema once a day. It was always in my head. And then the kids were born.”

Patinkin and Grody have two boys — Isaac is 15 and Gideon is 11.

At that point, he said, “I often increased the prayers.”

Before I die, I will write down what I pray so my kids can have my prayer book.”

The Jewish life Patinkin and Grody have with their kids is home-based.

They don’t go to synagogue much anymore, he said, even on the High Holidays, though they pay dues to a neighborhood Conservative synagogue.

“Every theater I’m in is a synagogue — it’s the place where I feel in touch with God and humanity,” Patinkin said.

They sent their older son to a Jewish day school through second grade, but found that the formality of the rules he was being taught, including kashrut, didn’t jive with how they live. They moved him to a private school with no religious affiliation.

Instead of attending Hebrew school, both of their boys have had private Hebrew tutors — and the older one became a Bar Mitzvah as the younger will be in a couple of years.

Patinkin often takes his older son, who loves nature, camping. One day, when they were backpacking in the mountains, they got lost.

Frightened, Isaac began reciting the Shema.

“That was nice,” Patinkin said. “I want to pass it on.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.

The Archive of the Jewish Telegraphic Agency includes articles published from 1923 to 2008. Archive stories reflect the journalistic standards and practices of the time they were published.