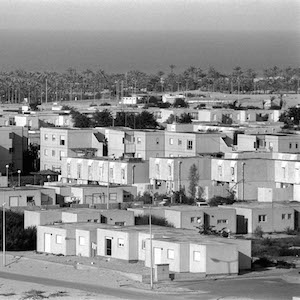

It is difficult to say what feelings fill the hearts of the 4500 Israelis in this pleasant seaside township on the northern Sinai coast and in the string of agricultural settlements built further inland on the desert sands. For these settlers, some Israel-born, others immigrants from Europe, the Soviet Union, North America and South Africa who opted for the pioneer life, know today that they will have to leave.

Not immediately, perhaps. But inevitably they will have to abandon their homes, shops, businesses, gardens and farms. They will be evacuated in accordance with a timetable to be worked out when Israel and Egypt begin shortly to negotiate a peace treaty within the Camp David framework that provides for the restoration of Sinai to full Egyptian sovereignty.

If there is anger and resentment in many hearts, that is understandable. What strikes a visitor, however, is a deep sadness and resignation mingled with an almost naive clinging to fragile hopes. The anger is directed mainly against the present Likud-led government of Premier Menachem Begin who signed the Camp David accords and now says the Sinai settlements must be liquidated in the interests of peace with Egypt. But there is also bitterness against the previous Labor-led regime that initiated the settlements 10 years ago and invited settlers to come to establish new homes and a new frontier.

HAILED AS HEROIC PIONEERS

They were hailed then as heroic pioneers, fulfilling a major tenet of the Zionist ideal and protecting Israel’s southern reaches for all times from enemy aggression. Of course, they were not protectors. Yamit and the surrounding villages were civilian outposts, requiring by their very nature the protection of Israel’s army and air force based in Sinai.

But in those euphoric years after the Six-Day War no one thought in such terms. Peace with Egypt was a remote possibility. President Anwar Sadat himself said, on many occasions, that it would not come in this generation.

Meanwhile, Yamit flourished. The settlers invested time, money, energy and love. Encouraged by the government in Jerusalem, others joined them. The politicians pledged repeatedly that the Sinai settlements would never be given up. Even after Sadat’s historic visit to Jerusalem last November, the settlers had reason to believe that Israel would never yield its Sinai holdings. Begin himself became an honorary member of one of the agricultural villages, declaring publicly that he intended to retire there when his term of office ended.

But there were ominous murmurings. Prominent leaders, such as Defense Minister Ezer Weizman and Foreign Minister Moshe Dayan–for whom Yamit was a pet project in the 1960s–began to hint that if the choice was ever between peace and the settlements, the settlements would have to go. When both returned from Camp David early last week, they said so flatly.

Sunday, the Cabinet, by majority vote, approved the Camp David accords, including the removal of the settlers contingent on a peace treaty with Egypt. Yesterday, Begin asked the Knesset for approval and he is considered virtually certain of winning it when the vote is taken later this week.

At 10 o’clock yesterday morning, a protest rally was held in the central square of Yamit in front of a huge monument to the 187 Israeli soldiers of an armored brigade that broke through the Egyptian lines in 1967. Nearly 1000 residents took part. They cheered spokesmen of the moshavim movement who told them not to despair, that there was still hope.

HOPE HAS DIED

But at another settlement on the seashore, some miles west of Yamit, hope has died. In that town stands a red granite monument to 10 Israeli airmen who were victims of a crash. One of them was the son of Justice Minister Shmuel Tamir. The minister had been an ardent supporter of the Sinai settlements and frequently visited them. But Sunday he voted to support the Camp David agreements. If he can abandon his son’s monument, then there is no hope, the settlers said.

Several score Sinai settlers were in Jerusalem Sunday with their tractors and bulldozers loudly protesting the abandonment of Sinai even as the Cabinet was debating. They were furious, partly because no member of the government would speak to them or visit Sinai to reassure the populace. More demonstrations are expected when the Knesset convenes to vote tomorrow.

Meanwhile, two groups of new settlers took over their homes yesterday in recently built villages in Sinai even though electricity has not been installed. Among them are 28 families of immigrants from the Soviet Union who are settling in Priel and 25 families from the U.S., Great Britain and South Africa who went to Tamei Yossef. They made the move now because they feared that if they waited they might be stopped by the authorities.

Agricultural work will go on for the time being. Crops must be planted and harvested. Business continues in Yamit, which has developed into a resort town. But much of the spark and energy has gone out of the enterprise. Some families and individuals are expected to depart in the weeks ahead and new job opportunities will decline.

When the time comes for the withdrawal from Sinai, the settlers will not leave as refugees. The government has pledged to resettle them elsewhere. But there will be bitterness. Once brave pioneers, the people of Yamit and the other villages see themselves now as mere bargaining points, pawns in the game of diplomacy who became expendable.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.

The Archive of the Jewish Telegraphic Agency includes articles published from 1923 to 2008. Archive stories reflect the journalistic standards and practices of the time they were published.