Until recently, Jewish characters in popular culture came in two types: assimilated and invisible.

But in the past few years, observant Jewish characters — and observant Jewish themes — have begun to come out of the closet.

It’s not a seismic shift: Many of the Jews portrayed in popular culture, particularly on television, still adhere to stereotypes, such as the shallow, shopaholic nanny or the wimpy, whining rabbi who appeared on a few “Seinfeld” episodes. And it’s not as if Jewish characters who keep kosher and Shabbat have suddenly flooded the nation’s theaters and bookshelves.

But there appears to be little doubt: A new Jewish character has emerged.

To name just a few books, Pearl Abraham’s recently released “Giving Up America” focuses on the dissolution of a marriage between a lapsed Chasidic woman and her Orthodox, but not Chasdic, husband; and Elizabeth Swados’ “Flamboyant” examines a relationship between a prostitute and a female Orthodox teacher at a New York City public school. For young adults, there’s Sonia Levitin’s “The Singing Mountain,” a portrayal of two teen-agers who confront spirituality and coming-of-age in a story set in both America and Israel.

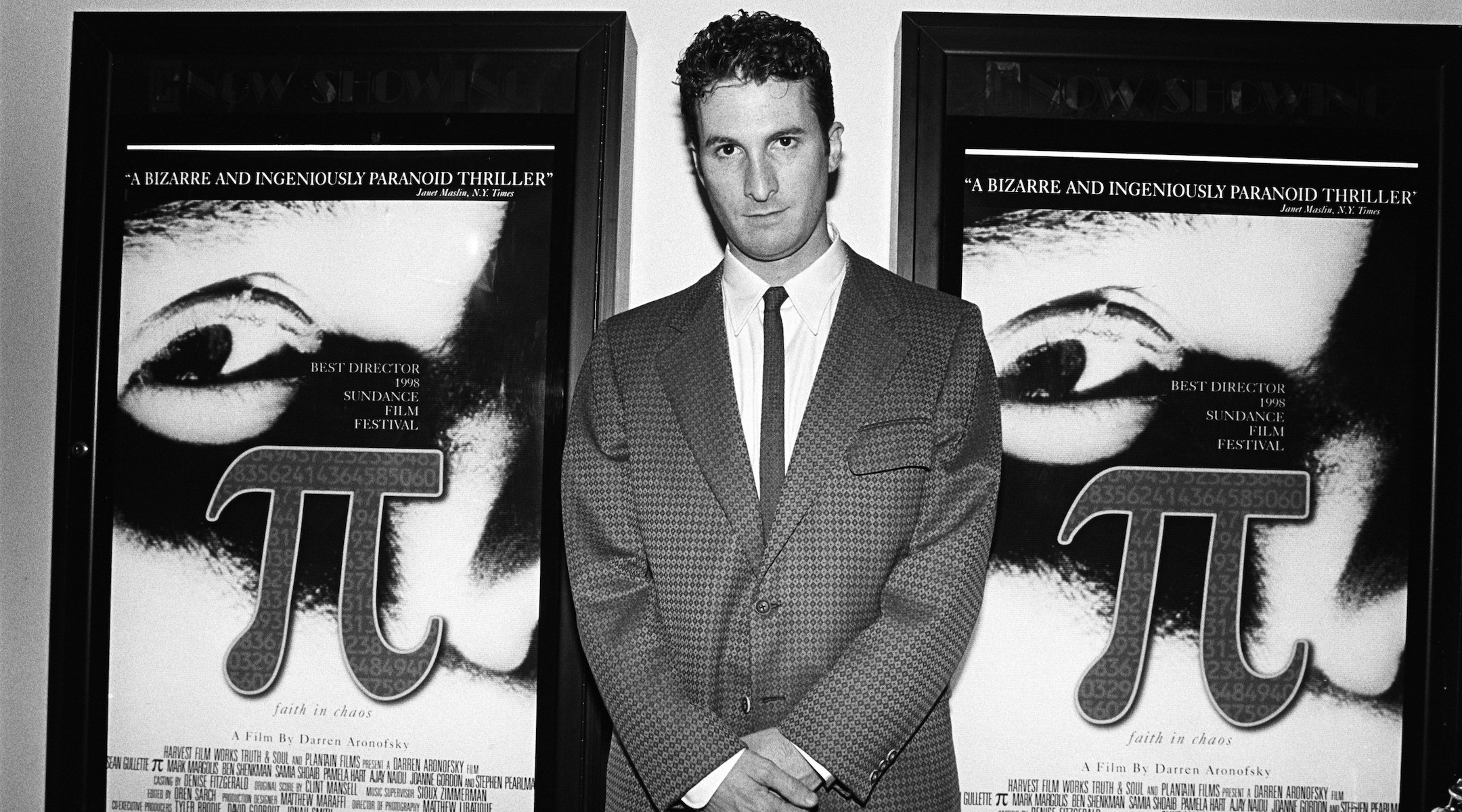

In the movie “Pi,” which opened in theaters earlier this year to wide critical acclaim, Chasidic Jews compete with a Wall Street firm for a man whom they believe knows the mathematical number sequence that holds the key to explaining the universe.

Scholars who follow the way Jews are portrayed in popular culture say the new character type reflects one of the threads in contemporary American Jewry.

“We’re living in a time when religion is not nearly as invisible as it once was,” says Samuel Heilman, a professor of sociology and Jewish studies at the City University of New York.

Since the great immigration of Jews to the United States began in the late 19th century, Jews’ involvement in American culture and arts has been out of proportion to their percentage of the population.

This involvement can be divided into three phases. Until World War II, Jews who were involved in mainstream culture put their Jewishness aside or worked explicitly in the Christian idiom — it was the son of a cantor, after all, Irving Berlin, born Israel Baline in Russia, who penned the lyrics to “White Christmas.”

In the second, post-World War II wave, Jewish artists began to address their own concerns, but their fictional characters were often ambivalent Jews who either wanted to cast nostalgic glances at the culture that nurtured them or break away from their pasts entirely.

As Daphne Merkin wrote recently in her New York Times Book Review of Allegra Goodman’s National Book Award-nominated “Kaaterskill Falls,” which portrays the lives of a tight-knit community of Orthodox Jews centered around their rebbe and the upstate New York town where they summer: “Jewish writers, by and large, have tended to focus on the merely ethnic — the long grip of overbearing mothers, the enduring allure of shikshas, the gustatory limitations of gefilte fish,” she wrote, acknowledging exceptions such as Chaim Potok and Cynthia Ozick.

“Religion belonged on Sunday morning or Saturday morning. It didn’t belong in the public sphere,” Chaim Waxman, a professor of sociology at Rutgers University, says of the postwar period.

Now, Jewish representations in popular culture appear to have entered a third phase, which, say scholar and trend-watchers, stems from several factors.

The growing visibility of observant Jews, ranging from simply traditional Jews to the fervently Orthodox, says Heilman, has made them “part of the political and social landscape. Particularly in America’s entertainment centers, New York and Los Angeles, “if you have writers looking for characters, they’re rubbing shoulders with guys in black hats and black coats.”

Popular culture’s current infatuation with religion in general, and Judaism in particular — Madonna and Roseanne have been reported to be studying the Kabbalah — accounts for another piece of the puzzle.

In addition, according to a recent article in the Jewish Journal of Greater Los Angeles, there are an increasing number of observant writers, directors and producers in Hollywood who are refusing to work on the Sabbath.

It’s not as if portraying observant Jews means that the characters are always going to be on target.

In this year’s film “A Price Above Rubies,” a scene shows a Chasidic couple kissing while traveling in a car on a busy street: an unlikely display of public affection in a very modest community.

“Complex communities are turned into cliches as `impossibly rigid’ Orthodox Jews and the `oversexed’ secular world demonize one another,” Sarah Blustain puts it in reviewing some of the new books written by and about Orthodox Jewish women in the upcoming issue of The Reporter, the magazine of Women’s American ORT.

And subjects once considered taboo even within the Jewish community are fair game in pop culture as well.

In what is perhaps the funniest scene in the recent movie “The Big Lebowski,” Dude, played by Jeff Bridges, and Donny are sitting in their favorite haunt, the bowling alley, when their friend Walter erupts in anger after he is told that their next match is scheduled for a Saturday.

“How come you don’t roll on Saturday, Walter?” asks Donny, played by Steve Buscemi.

“I’m Shomer Shabbas,” answers Walter, played by John Goodman.

“What’s that, Walter?” asks Donny.

“Saturday, Donny, is Shabbas, the Jewish day of rest. That means I don’t work, I don’t drive a car, I don’t handle money” and, Walter adds, using epithets, that he certainly doesn’t bowl on Shabbas.

What gives this an added twist is that Walter converted to Judaism to marry a woman from whom he was later divorced. He was born a Polish Catholic and has the accent and mannerisms of a stereotyped member of that group from, say, Chicago — picture “The Blues Brothers” without the sunglasses — with the added twist of being a Jew by choice.

But even characters that some may find offensive represent a certain maturity in Jewish portrayals, says Shimon Wincelberg, who has worked in Hollywood since the early 1950s.

“In the old days, you could never portray a sleazy character as a Jew. Nowadays, anything goes,” he says.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.

The Archive of the Jewish Telegraphic Agency includes articles published from 1923 to 2008. Archive stories reflect the journalistic standards and practices of the time they were published.