NEW YORK, Sept. 16 (JTA) — A man with a chiseled face and Roman profile gazes into the light amid a roomful of Greco-Roman busts that could be of his ancestors. A silver-haired Indian merchant sits in his opulent Calcutta living room, a servant holding his tea tray. Jewish school students stand atop a pyramid alongside a faux Sphinx and palm trees in Las Vegas. During a recent interview, photojournalist Frederic Brenner sifted through these images, stopping to point at one black-and-white image of a young Italian Jew whose visage seemed to morph into the marble statues. “This capacity of becoming the Other — this is what the whole project is about,” he says. The project Brenner is referring to is “Diaspora: Homelands in Exile,” a two-volume set of photographs and essays due out Sept. 30 from HarperCollins. In many ways, it encapsulates his life´s work. Brenner, 44, is the controversial chronicler of world Jewry who for 25 years roamed five continents living with and photographing indigenous Jews — from Azerbaijan to Yemen and Brooklyn to Jerusalem. It was his 1996 “Jews/America/A Representation,” which included a roomful of Groucho Marx impersonators, a chapter of Harley-Davidson riders and a table of semi-naked women displaying their mastectomy scars, that brought his name to the coffee tables of many American Jews. The book also exposed a debate over the nature of this new form of Jewish documentary. For Egon Mayer, a noted sociologist whose 2001 survey of American Jewish identity was widely seen as a benchmark study, Brenner´s highly stylized portraits of U.S. Jews recorded a whimsical, irreverent but loving slice of life. “These are not photographs either of or for comfortable Jews,” he wrote, but unearth “the layered personae” of American Jewry. There were photos of Jewish Civil War enthusiasts, Jews at a Catskills singles resort, and famous Jews like Dustin Hoffman and Henry Kissinger. But author and commentator Leon Wieseltier, writing in The New Republic, said the Jews in the book were “exploited in a cheap culture game.” “Brenner´s pictures adore themselves. They believe themselves to be fresh, shocking, paradoxical, controversial,” he wrote. “See how they blow the lid off American Jewish identity and go behind the conventions of American Jewish existence and boldly reveal it to be riddled” with irony. Still, Mayer says Brenner´s latest work surfaces at a crucial moment — after the release of the National Jewish Population Survey, a $6 million study said to provide the most comprehensive statistical snapshot of U.S. Jewry ever. Brenner´s art captures something facts and figures cannot, Mayer says. He “can do artistically what we social scientists are trying to do by asking 1,000 questions,” Mayer says. Whether it´s the photo of Russian immigrant taxi drivers lining up their cabs on Coney Island or a picture of the lesbian daughters of Holocaust survivors, Brenner “is trying to capture a complexity that Jewish institutional organizations are uncomfortable with,” Mayer says. This latest collection features more than 500 of Brenner´s photographs, and for the first time in any of his five books includes commentary by such figures as French philosopher Jacques Derrida and black-Jewish professor Julius Lester, as well as his own notes. For Brenner, his pictures always represented “the enigma of identity” for Jews, “of dispossession and dispersal that is not only passively experienced but deep within us.” He points to one photo in particular, from the Soviet Union in 1983. Brenner saw beyond the stereotypical Iron Curtain of urban refuseniks by trekking to then-unmapped Central Asian republics, among the first Western photographers allowed in, he says. In Azerbaijan, he found mustachioed Jewish men in a local tea house looking much like their countrymen. “Jews take the shape and color of where they are. All identities are invented, even ours,” he says. His mission to explore that identity began in 1978, when Brenner, 18, the assimilated son of French parents, launched his own search for identity with a trip to Israel. His maternal grandparents came from Algeria and his paternal grandparents from Romania and the Ukraine, assembling a familial “puzzle” he´s been piecing together since. Schooled as an anthropologist, he began taking pictures, including of the fervently Orthodox Jerusalem neighborhood of Mea Shearim. There, he recalls, white, European Jews “reproduced a shtetl” in the Land of Zion, but he saw it as only a fragment of the whole Jewish picture. Armed at first with foundation grants, Brenner began traveling in the early 1980s to the Soviet Union to learn how Jews retained their ethnic identities. That turned into a 12-year marathon to more than 80 countries driven by a desire to record communities of “vanishing” Jews. Whether it was Ethiopia or Uzbekistan, he found “an incredible reservoir” of Jewish culture intertwined with other worlds, and he was determined to unravel that thread before it disintegrated. One haunting image comes from a community of rural Yemenite Jews. A grandfather reads a Jewish text with his young grandson. Years later he found that boy, a teenager named Mazal — Hebrew for “fortune” — in an Israeli absorption center. Mazal, then 16, along with his 14- year-old wife and infant daughter, are transplanted to Israel, but they seem hardly changed outwardly. Today that baby girl is 12. She lives with her religious parents and four siblings in the Tel Aviv suburb of Rehovot. She loves to roller blade. Brenner embraces these stories of exile and home with a spiritual fervor of his own. He recounts the story of Abraham, who obeys God´s commandment to “Lech l´cha — “Go forth” — by journeying into the wilderness of Canaan. And God in Deuteronomy commanded the Jews to remember the laws of Israel by affixing a mezuzah to the doorposts of their homes. Brenner points out that the word mezuzah derives from the Hebrew verb “zuz,” or go. Jews “are both sedentary and nomads,” he says. “This injunction, ‘Lech l´cha,´ is not a curse — it´s truly a project, a vocation. History unfolds and enables the Jewish people to accomplish this vocation.” Often Brenner finds Jews at their place of work, like the Tajik barbers in a local barber shop from his first trip to Tajikistan, and later the same group after they had immigrated to Israel — posing in the Dead Sea. In another photo, he shows Italian Jews at St. Peter´s Square outside the Vatican, selling pictures of the pope. “Not only didn´t they succumb to the temptation to idol worship — they are selling the idols,” he says. The more he sees, Brenner says, the less he understands about the world´s Jews.

Photojournalist focuses on Jews in exile

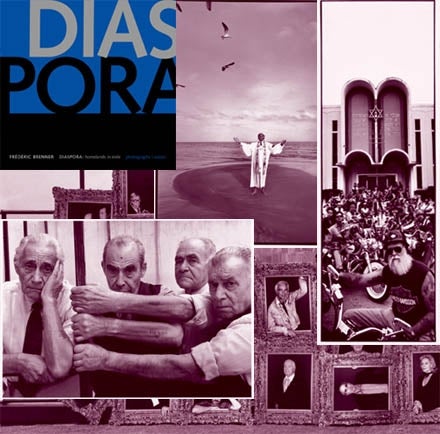

Photos from Frederic Brenner's book, Diaspora. ("Frederic Brenner, courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery")

Advertisement