If the 1920s were truly the “Golden Age of American Sports” causing scribes for Harper’s Magazine to declare that games like college football were “almost a national religion,” then Jews were among the most devoted worshippers. But while Jews surely extolled the Red Granges, not to mention the Babe Ruths and Jack Dempseys of that era, there also was a Jewish pantheon of heroes whom they revered. Second generation American Jews, reared in this country, lionized those who battled or fought there way out of Jewish neighborhoods to prove to all comers that Jews were as manly and as American as all others. (For decades Jewish women athletes — fewer in numbers — did not get the recognition they deserved for their own re-defining of robust American Jewish femininity.)Jewish fans knew everything there was to know about athletes like Benny Leonard who was king of the welterweight class during a decade where no fewer than 27 Jewish fighters held world titles. They followed the hard wood trails of Nat Holman as he barnstormed with the Original Celtics basketball club, were captivated by Benny Friedman who first starred at Brooklyn’s Erasmus Hall High School and then quarterbacked the University of Michigan before becoming one of the early luminaries of the fledgling National Football League. Though not a primary area of focus, this era of extreme fandom and athletic accomplishment did not escape the attention of the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

A perusal of the JTA’ archives reveals that early on its reports sometimes contained more than a congratulatory and celebratory tone. They possessed sensitivity to underlying Jewish tensions highlighted and fostered by sports not to be found in American tabloids. See, for example, the April 18, 1926 report on the Mizrachi (Religious Zionist) Organization’s criticism of Hakoah-Vienna, the greatest Jewish sports team of its time, playing games on the Sabbath as part of its triumphant nation-wide tour of the United States after its soccer club had won the Austrian National Championship. JTA pieces recognized that sports defined the Jews’ status in America and in the world, anticipating the development of a mature present-day Jewish sports history that analyzes more than it idolizes. Thus, six days earlier, JTA reported how representatives from the Austrian athletic club explained to U.S. President Calvin Coolidge that sports were contributing mightily to the physical development of Jews in Europe. JTA understood that the question of how Jews were treated as athletes, as well as how they comported themselves on the field, track, court — and even at the White House — often reflected on essential communal issues of identification and religious continuity.

JTA continued to report on sports in the 1930s, even introducing a regular column dubbed “Slants on Sports.” And the triumphs of Jewish athletes, like boxing champion Barney Ross, continued to serve as a source of pride. At the same time, JTA captured the Jewish anxiety of that era, with intense coverage of anti-Nazi boycotts and protests surrounding the 1936 Olympics in Berlin.

The Olympics would return to Germany in 1972, and once again attract intense attention from JTA — this time with the murder of Israeli athletes in Munich.

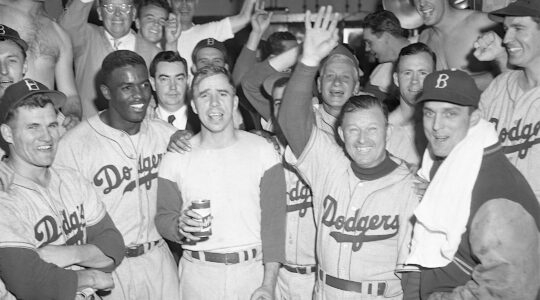

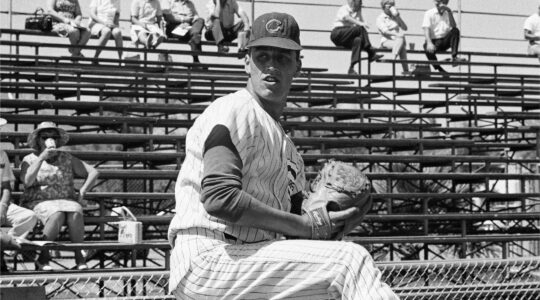

In between the 1936 and 1972 Olympics in Germany, JTA’s coverage of sports was sporadic, sometimes completely ignoring important Jewish athletes like basketball great Dolph Schayes. Sandy Koufax garnered a burst of attention in 1963, with the Dodgers reshuffling its pitching rotation to accommodate the hurler’s decision not to pitch on the High Holidays, and his subsequent masterpiece in the opening game of the World Series. But not a word two years later when Koufax sat out Game 1 of the World Series because it fell on Yom Kippur.

One exception to this dearth of sports coverage was the Maccabiah Games, which regularly garnered attention.

By the 1970s, JTA’s sports coverage began to broaden again, with reports on the accomplishments of Jewish athletes, as well as the fits and starts of those who have tested the limits of sports accommodation to Jewish religious values. Most notably, the JTA was on the scene when, in the late 1990s, Baltimore high schooler Tamir Goodman attempted to experience the ultimate observant Jewish fantasy of having the sports world bend to his every need in his quixotic attempt to play big-time college basketball while staying true to his Orthodox practices.

Thus the “sports section” of JTA’s archive is an essential tool for both the amateur Jewish sports historian anxious to recount athletic achievements over the last nine decades and the professional intent on explaining what these sports encounters have meant to Jews and Jewish history.

Jeffrey S. Gurock is the author of “Judaism’s Encounter with American Sports” (Indiana University Press, 2005).