JTA is introducing a new column, “Seeking Kin,” that aims to help reunite readers with long-lost friends and relatives.

BALTIMORE (JTA) — Eliyahu Finkelstein grew up in the only Jewish family in the village of Zavizov in northwestern Ukraine, escaped from the Nazis after losing his parents and sister, fought in the Red Army disguised as a Russian gentile, served in North Korea, then wound his way through Europe to Israel two months following the state’s founding in 1948. In Israel, he spent most of his career delivering cream, yogurt and cheese for the Tnuva dairy cooperative. Finkelstein and his wife, Yaffa, also a Shoah survivor, raised a daughter, Esther, and a son, Boaz, who produced five children between them.

Now 88 and living in the Tel Aviv suburb of Givatayim, Finkelstein recently decided to search for a long-lost branch of his family that settled in Philadelphia.

Finkelstein has only eight-decade-old facts to go on, but hopes that JTA’s readers can recognize enough threads of information to assist in his search.

What Finkelstein knows is that his paternal uncle immigrated to the United States in the 1920s and changed his name from Shimon Finkelstein to Sam Stone. Stone often wrote to his father, Eliyahu Finkelstein’s grandfather Shmuel — who lived back in Zavizov with Eliyahu; Eliyahu’s sisters, Rosa (who died at age 6 of scarlet fever) and Chana, and their parents, Pesach Wolf (known as Muni) and Esther. Eliyahu Finkelstein’s father told him that Stone’s first job in Philadelphia involved standing outside a grocery store, wearing a tallit and tefillin, to entice Jewish customers to purchase kosher food there.

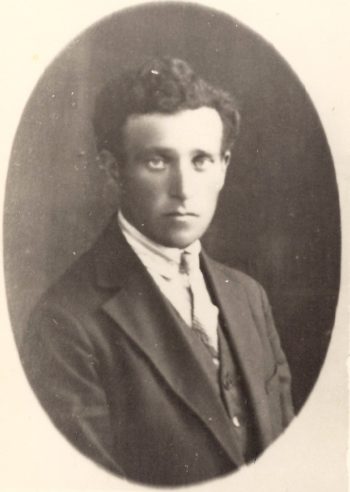

Pesach Wolf “Muni” Finkelstein, above, had a brother who immigrated to Philadelphia before World War II and changed his name to Sam Stone. (Courtesy of Eliyahu Finkelstein)

Finkelstein also recalls Stone’s letters in the 1930s sometimes containing $25 in cash — “a ton of money then,” he says. Stone once sent a photograph of his new American family — there were four children, Finkelstein thinks — which included a hunchback daughter.

“All these years, I never searched for them because I know that sometimes there is bad blood directed (toward the seekers), out of concern that money or assistance is sought. … I didn’t want to be seen by them as a loser, as someone who needs help or something,” Finkelstein says of the Stones.

“Now, I’m 88, and I want them to know that someone is alive from their family. I don’t want anything from them — just for them to know that someone is left. My (immediate) family was killed, so there’s no one remaining.”

The family of Eliyahu Finkelstein, third child to the right. (Courtesy of Eliyahu Finkelstein)

Finkelstein’s grasp of the details of his past remains strong. He can plot Zavizov’s precise location: eight kilometers from the town of Hoshtch and 28 from Rovno. The village of Bukhariv (one kilometer away) contained three Jewish families: Finkelstein’s uncle, Lieber, and two with the surname Ronion; Bashyne (two kilometers away) had two Jewish families, and the five Jewish households in Pezov (three kilometers away) all were from the Dorfman clan. Jews in the three villages walked to the Finkelstein home for Shabbat and holiday services, since Shmuel owned a Torah scroll.

Jewish life ended when the German army conquered the region in 1941 from the Russians, who had held it two years. Finkelstein says his father died at 48 of “heartbreak” after learning that two of his brothers were among the 17,500 victims of a Nazi massacre.

“He heard the news on a Wednesday and walked around, not saying a word,” Finkelstein recalls. “Thursday evening, he said he didn’t feel well and lied down in bed. Friday morning, he was dead.” Two other of his father’s brothers and their families were murdered later in Hoshtch and Buhryn, respectively.

The Nazis deported Finkelstein, Esther and Chana to the ghetto of Ostroh, 20 kilometers away. The women were murdered there in late 1942 with the ghetto’s other prisoners. Finkelstein heard the news while working in a granary at a German labor camp nearby, and fled immediately to the forest. A gentile friend procured for him a Russian army uniform of slacks, shirt and boots. Finkelstein invented a new identity: an escaped Russian prisoner of war, Pvt. Sergei Bondarchuk. Through the next summer, he farmed the land of a Czech immigrant, Kovac Voitek, in Krayev, near a forest. Finkelstein joined the partisans, then fought with the Red Army in Ukraine, Hungary and Czechoslovakia. He was in Prague when the war ended, and remained in the cavalry and artillery corps until being discharged in May 1947. Upon arriving in Israel, he fought for an armored unit in the War of Independence in the Negev and Sinai.

Only in the mid-1990s did Finkelstein begin reconnecting with his roots. He contributed toward the erection of a Shoah monument at Ostroh, which he quickly notes is where 1,015 Jews were killed. In 2002, he returned to his homeland for the first time, joining a group going to Hoshtch, his grandfather Shmuel’s hometown, near Zavizov, to dedicate a monument to the 3,200 Jews buried in a common grave there. Visiting Hoshtch and Zavizov left Finkelstein feeling empty.

“I said Kaddish and stood there for 20 minutes. What else could I do?” he explains. “The Ukrainians destroyed our house, and there was nothing there. My grandfather had a barn for cows, and they destroyed it. I spoke to a Ukrainian there, who told me that they’d destroyed buildings because they thought the Jews had hidden gold there.”

Finkelstein recently set out to locate his cousins and their descendants. He wrote to an Israeli radio program that helps reunite long-lost relatives and friends. The host read the letter on-air in mid-June. Few of the show’s cases feature searches for Americans, but, Finkelstein says, perhaps “a miracle” will occur.

“Since age 3, my daughter always dreamed of having a grandfather, a grandmother. ‘Why does everyone else have (them), and I don’t?’ she’d ask,” says Finkelstein, who is about to become a great-grandfather.

“There were 43 people on both sides of my family, and I’m the only one to have survived. If we can find our relatives, I’d tell (Esther) that she now has a family. I would be able to call them, say hello and invite them to visit us in Israel. I’d love it.”

Send a message to seekingkin@jta.org if you can help Eliyahu Finkelstein locate his American relatives or would like our help in searching for your own long-lost friends or family. Please include the principal facts in a brief e-mail (up to one paragraph) and your contact information.