(JTA) — It’s a fact of life: Scores of notable people pass away each year. But for some reason — whether it’s the continued aging of the baby boomer generation, the increasingly loud echo chambers on social media or maybe just the expansion of who (or what) constitutes a celebrity in our collective psyche — 2016 was marked with an unusually high number of high-profile deaths, including David Bowie, Prince and Muhammad Ali.

Within the Jewish world, there were striking losses, too — including, just as the year came to the close, George Michael and Carrie Fisher, both of whom had Jewish roots. The past year has taken many notable and influential members of the tribe from all walks of life. Here are just a few of those whose passings left a lasting mark on 2016.

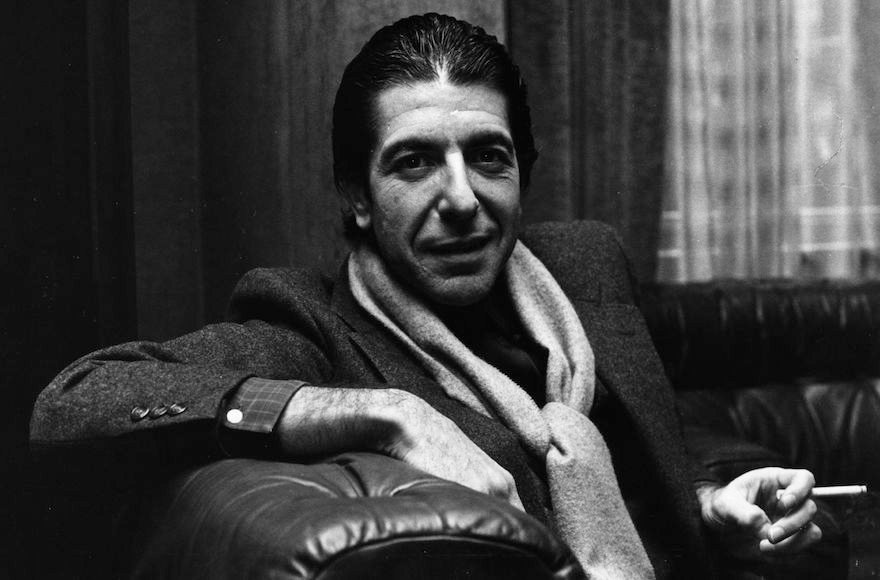

Leonard Cohen, 82

Leonard Cohen sharing a joke and smoking a cigarette in 1 980. (Evening Standard/Getty Images)

Few artists have so poetically infused Jewish influences into popular music like Leonard Cohen. The grandson of a rabbi, Cohen grew up in Montreal in an Orthodox household. He wrote several books before releasing his first album in 1967 at age 33. He would go on to release 13 more albums and spawn hits such as the now ubiquitous “Hallelujah,” which has been covered dozens of times since its debut in 1984. Cohen’s meticulously crafted songs — evolving in genre from sparse, finger-picked folk to synth-pop to light rock — explored heavy spiritual, sexual and religious themes. He remained an observant Jew throughout his life despite a deep exploration of Buddhism and performed in Israel several times. The songwriter died in November, three weeks after releasing his final album, “You Want it Darker.” The title track included a chorus with the Hebrew word “hineni” (“here I am”): “Hineni, I’m ready my Lord.” In an October interview he had told the New Yorker, “I am ready to die.”

Ruth Gruber, 105

Ruth Gruber at The Paley Center for Media in New York City, Feb. 3, 2011. (Andy Kropa/Getty Images)

While many female journalists of the 1930s and ’40s were confined to newspapers’ social pages, Ruth Gruber — one of the 20th century’s most important chroniclers of the plight of Jewish refugees — was breaking historic ground. After earning her doctorate at 20 — one of the youngest in the world at the time to accomplish that — Gruber was sent by the New York Herald Tribune to the Soviet arctic and became the first Western journalist, male or female, to report from there. This won her a job under Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes in 1941. In 1944, amid the Holocaust, President Franklin Roosevelt sent her to Italy to comfort a group of Jewish refugees from 19 Nazi-occupied nations who were preparing to immigrate to the U.S. She went on to report on several defining moments that led to the development of the State of Israel — from the Nuremberg trials to the British interception of Exodus 1947, a ship with thousands of Jewish refugees headed to British Mandatory Palestine. “I just felt that I had to fight evil,” she said in 2001. “And I’ve never been an observer. I have to live a story to write it.”

Elie Wiesel, 87

Elie Wiesel in Paris after being awarded the French literature Medicis Prize for his novel “Le Mendiant de Jerusalem,” Nov. 26, 1968. (AFP/Getty Images)

Nobel Prize winner, writer of over 50 books, moral conscience — the honors and titles abound for Elie Wiesel. As JTA’s Ben Sales wrote after his passing in July, the “Night” author’s books and activism seared the horrors of the Holocaust into American cultural consciousness and arguably did more to unite American Jews than any other figure. After his death, the House of Representatives approved a resolution honoring his life, which included a proposal to build a memorial statue of Wiesel at the Capitol. He was also honored with a photo exhibition in Russia, whose Jewish community he advocated for in his 1966 book “The Jews of Silence.”

Shimon Peres, 93

Shimon Peres speaking during an interview in the president’s residence in Jerusalem, April 10, 2013. (Lior Mizrahi/Getty Images)

Few people had as much of an impact on Israeli history as Shimon Peres. In fact, Peres — born Szymon Perski in Wiszniew, Poland — fought for Israel before it was a state, leading divisions of the Haganah, the precursor to the Israel Defense Forces. He would go on to hold numerous Cabinet positions — including minister of defense and of foreign affairs — and served as president from 2007 to 2014. (And while he never won an election to become prime minister, he filled that position three times.) Over his decades in public service, Peres won a Nobel Prize for negotiating the 1993 Oslo Accords with Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat and became a symbol of the movement for peace between Israel and its Arab neighbors — something he promoted until his death in September. “A light has gone out, but the hope he gave us will burn forever,” President Barack Obama said in a statement. “Shimon Peres was a soldier for Israel, for the Jewish people, for justice, for peace, and for the belief that we can be true to our best selves — to the very end of our time on Earth.”

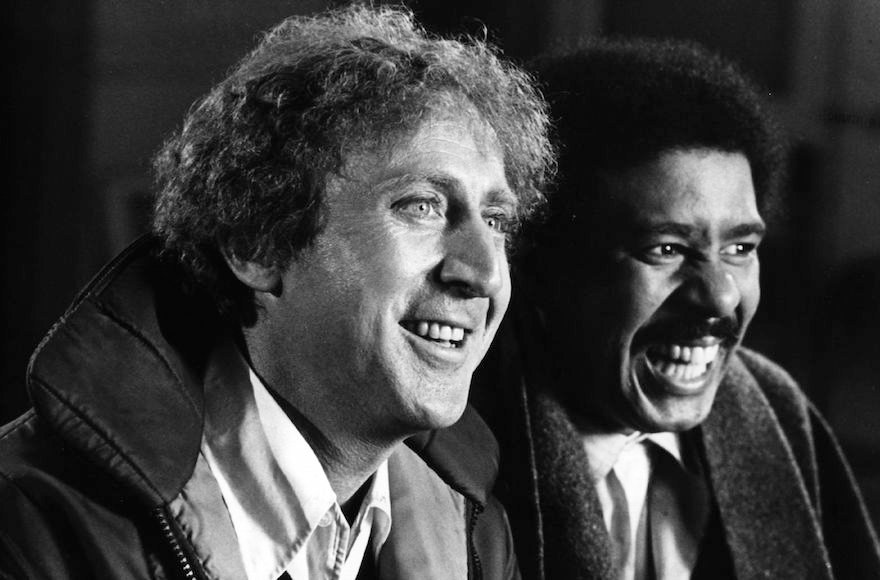

Gene Wilder, 83

Gene Wilder, left, shown with Richard Pryor, got a lot of love from celebrities on Twitter. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

From Willy Wonka to Frankenstein’s grandson to the rabbi in “The Frisco Kid,” Gene Wilder — born Jerome Silberman — played some of the quirkiest, most beloved film characters of the 1970s and ’80s. After Mel Brooks gave him his first major role as Leopold Bloom in “The Producers,” the Jewish comedic team went on to collaborate in other classics such as “Blazing Saddles” and “Young Frankenstein,” both from 1974. As a teenager, Wilder spent time at a military school, where he claimed he was beaten up for being the only Jewish student. In 1984, he married Jewish comedian Gilda Radner, who died of ovarian cancer in 1989. In addition to acting, screenwriting and directing, Wilder went on to publish multiple novels and a short story collection. He died of complications from Alzheimer’s disease in August.

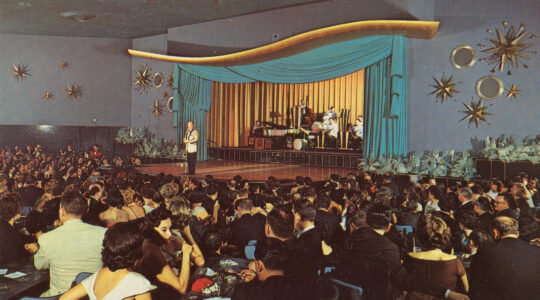

Esther Jungreis, 80

Esther Jungreis in 2016 (Hineni.org)

Many try to promote observance among the Jewish masses, but only one was nicknamed the “Jewish Billy Graham.” Jungreis, who as a child in Hungary survived the Holocaust, founded the Hineni organization in 1973 with the aim of bringing young Jews into the Orthodox fold. In addition to holding colorful rallies for the cause that often included elaborate lighting and musical accompaniment, she wrote self-help books and organized classes and singles events. In 1973, Jungreis held a rally at Madison Square Garden to inspire Jewish awakening; 10,000 people came. “The Rebbetzin,” as she was commonly known, died of complications from pneumonia in August.

Garry Shandling, 66

Garry Shandling arriving at the world premiere of “Iron Man 2” in Hollywood, April 26, 2010. (Frazer Harrison/Getty Images)

Before shows like “Curb Your Enthusiasm” and “Louie” gave viewers a behind-the-scenes look at the comedy industry, there was “The Larry Sanders Show,” Garry Shandling’s Emmy-winning and somewhat dark take on the life of a late-night talk show host. And before “Larry Sanders,” Shandling created an even more meta show with an appropriately postmodern name: “It’s Garry Shandling’s Show,” which frequently saw its creator break the fourth wall. But before all of this, Shandling was born to Jewish parents in Chicago. He became a respected standup comedian before getting into TV and eventually mentored other comics, including Sarah Silverman and Judd Apatow. “Yesterday we lost our most brilliant comic mind,” Silverman wrote after his passing in March from complications due to hyperparathyroidism. “The symptoms are so much like being an older Jewish man, no one noticed!” Shandling said in an episode of Jerry Seinfeld’s “Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee,” filmed not long before his death.

Doris Roberts, 90

Doris Roberts at the Fourth Annual Comedy Celebration Benefiting the Peter Boyle Fund in Beverly Hills, Calif., Nov. 13, 2010.

She is most widely known as the snappy Italian mother of Ray Romano’s character on the hit sitcom “Everybody Loves Raymond”— a role that earned her four Emmy Awards — but Doris Roberts (née Green) was proud of her Russian Jewish heritage. Although she primarily played mothers or grandmothers in the late stages of her career, her six decades in theater, television and film also included roles on the detective show “Remington Steele” and films such as “The Honeymoon Killers” and “The Taking of Pelham One Two Three.” Roberts told the Jewish Virtual Library that one of her favorite roles was in “Hester Street,” a film about a family of Russian-Jewish immigrants living in New York City. (She was born in St. Louis but was raised in the Bronx). She passed away in her sleep in April.

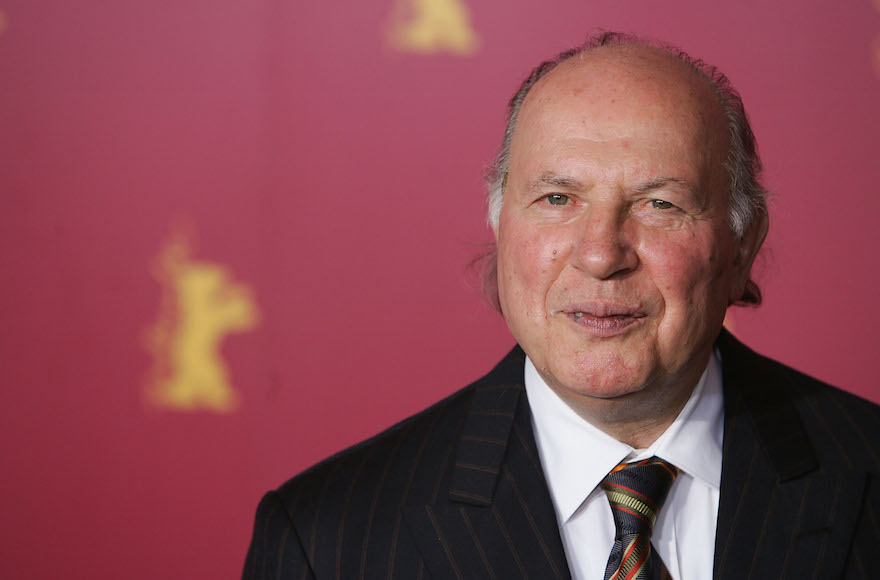

Imre Kertesz, 86

Imre Kertesz posing at the 55th Berlinale International Film Festival in Berlin, Feb. 15, 2005. (Pascal Le Segretain/Getty Images)

Many novelists who have taken on the Holocaust seek to evoke a sense of empathy from the reader through intense or graphic description. By contrast, the novels of Imre Kertesz — recipient of the 2002 Nobel Prize in Literature — seek to describe life in Nazi concentration camps as faithfully as possible, without indignation. Take the Nobel committee’s description of “Fateless,” his 1975 book: “The novel uses the alienating device of taking the reality of the camp completely for granted, an everyday existence like any other.” The Nobel award was extremely unexpected for Kertesz, who worked in relative obscurity in his native country of Hungary, where he supported himself by translating German works. “What I discovered in Auschwitz is the human condition, the end point of a great adventure, where the European traveler arrived after his 2,000-year-old moral and cultural history,” he said in his acceptance speech.

Meir Dagan, 71

Former Mossad chief Meir Dagan attending the Moskowitz Prize for Zionism ceremony in Jerusalem, May 30, 2011. (Kobi Gideon/Flash90)

After a decorated 30-year career in the Israel Defense Forces, in which he rose to the rank of major general, Meir Dagan became known as one of Israel’s most brilliant military minds. He went on to head the Mossad, where among his accomplishment he was credited with overseeing the creation of the Stuxnet virus, which wiped out a fifth of Iran’s nuclear centrifuges. Dagan, who headed the Israeli intelligence agency from 2002 to 2011, also wasn’t afraid to blast Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s hawkish posture toward using a military option against Iran. But when he died of liver cancer in March, even Netanyahu had high praise for him — and referred to a photo of Dagan’s grandfather in a Nazi camp about to be killed. “Meir was determined to ensure that the Jewish people would never be helpless and defenseless again,” Netanyahu said.

Anton Yelchin, 27

Anton Yelchin at the Tribeca Film Festival in New York City, April 19, 2014. (Larry Busacca/Getty Images)

It might sound cliché, but the untimely death of Russian-Jewish actor Anton Yelchin can only be described as a freak accident. Friends found Yelchin — a rising Hollywood star who appeared in dozens of films, such as the “Star Trek” reboot series — pinned between his Jeep and a brick pillar in the driveway of his Los Angeles home on June 19. He had apparently left the car, which rolled into him, in neutral. However, soon after the accident, The Associated Press revealed that the model of Jeep Yelchin owned was in the process of being recalled for a problem with its gear shift that made it difficult to tell when it was in park. Yelchin’s parents, former figure skaters who qualified for the 1972 Olympics (but were not permitted to compete by Soviet authorities, likely because they were Jewish), have sued Fiat Chrysler over the tragic incident.

Goldie Michelson, 113

Goldie Michelson in 2008. (Clark University)

Who would have thought that two Jewish bubbes named Goldie would be two of the oldest people in the world? After the passing of Goldie Steinberg last year, Michelson likely became the oldest Jewish person in the world. Then, after the passing of Susannah Mushatt-Jones in May, Michelson became the oldest living American. Michelson, née Corash, migrated with her family from Russia at the age of 2 to Worcester, Massachusetts, where she lived for over a century. She wrote her master’s thesis at Clark University on the Jews of Worcester and volunteered for Hadassah. The secret to her longevity? It’s a simple one: walk every day (although she enjoyed chocolate and lobster, too). She passed away in July, only a month away from her 114th birthday.