BROOKLINE, Massachusetts (JTA) — The well-worn books that fill the shelves in David Shrayer-Petrov’s living room reveal the remarkable literary life of the influential refusenik, who has left his mark both as a distinguished physician and as an acclaimed writer.

Among the volumes are works by literary lights of Russian 20th-century literature, including novelists Mikhail Bulgakov and Vasily Aksyonov, a peer of Shrayer-Petrov dating back to the 1950s, and the poets Boris Pasternak and Genrikh Sapgir, his close friend until the poet’s death.

But it’s the copies of the writer’s own globally published works that bear witness to Shrayer-Petrov’s triumph against the oppressive and anti-Semitic control exerted by Soviet officials who tried to silence the voice of the masterful and influential writer.

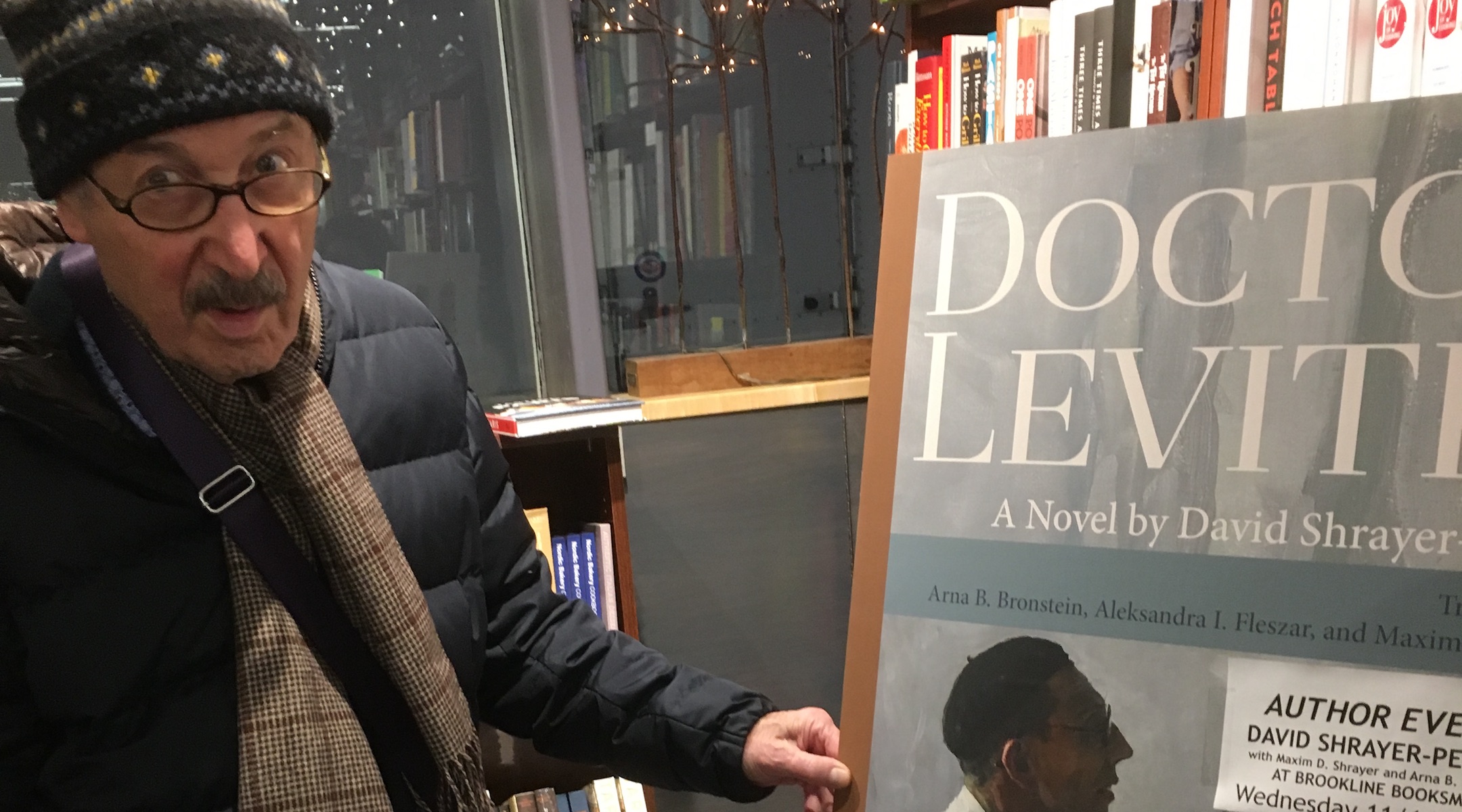

Now, with the publication of “Doctor Levitin,” the warm and cordial 82-year-old can boast another literary milestone, the first English-language translation of his groundbreaking novel. Written some 40 years ago, it is a harrowing tale that probes the experience of refuseniks and the fraying of the deep-rooted relationship between Russian Jews and their country.

Shrayer-Petrov wrote the novel between 1979 and 1980, the beginning of his family’s eight-year-long ordeal of living as refuseniks — would-be emigres kept in limbo by the USSR’s cruel and fickle bureaucracy.

Four decades ago, in January, 1979, Shrayer-Petrov, his wife, Emilia Shrayer, a literary translator and also a refusenik activist, and their then teenage son Maxim applied for exit visas to leave the Soviet Union.

The life-changing consequences were immediate: Shrayer-Petrov was stripped of his academic medical position and soon thereafter, tossed out of the Union of Soviet Writers. Shrayer-Petrov worked in a hospital emergency room and drove an illegal cab at night. The family faced insidious anti-Semitic harassment and Shrayer-Petrov was subject to harassment by the KGB.

Against this backdrop, as the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, Shrayer-Petrov penned his panoramic novel of a Jewish doctor, his non-Jewish Russian wife and their teenage son whose once comfortable lives spiral downwards in unimaginable and tragic ways after they apply to leave their homeland.

Three years later, Shrayer-Petrov completed “May You Be Cursed, Don’t Die,” the second novel of what would eventually become a trilogy.

Against all odds, in 1986, after the manuscripts were secretly photographed and smuggled out to the West, an abridged version of the first book was published in Israel, under the title “Being Refused.” The Russian-language novel became the first published work of literature on the refusenik experience.

A year later, in 1987, the family was finally granted permission to emigrate. They settled in Providence, where Shrayer-Petrov worked for some two decades as a cancer researcher at Brown University and continued to write. More recently, the couple relocated to this town that borders Boston, close to their son and his family.

David Shrayer-Petrov, in front of a portrait by the Russian-American artist Anatoly Dverin. (Courtesy of Maxim Shrayer)

“Doctor Levitin” (Wayne State University Press), was translated by Arna B. Bronstein, Aleksandra I. Fleszar — both of whom have translated other works by Shrayer-Petrov — and Maxim Shrayer, the author’s son, a writer and professor of Russian, English, and Jewish Studies at Boston College, who has overseen the translation of his father’s writing.

“I am happy this book is in English and it can be read by [American Jews] and Russian Jews,” as well as non-Jewish readers, Shrayer-Petrov said in a wide-ranging conversation at his home.

The ever humble and gracious writer is quick to acknowledge the painstaking contribution of his translators, and he is pleased with the results.

In 2006, he wrote “The Third Life,” the final book of the trilogy. In the years since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, three Russian-language editions of the novels have been published in Moscow and St. Petersburg.

Emotions swing wide in the richly textured and exquisitely written first volume. Its protagonist, Herbert Anatolyevich Levitin, and his wife Tatyana Vasilyevna, fear for their son Anatoly’s future as he faces the draft. And yet, with hints of hope, young love blossoms and in one scene, Tatyana brings a sense of purpose and even adventure as she prepares the family for an uncertain exit.

“Everything in the book was based in the real life of refuseniks, but as with all forms of art, it is a work of literary imagination,” Shayer-Petrov said, sitting at his living room table with his son and offering a guest a scone from a favorite local bakery.

Its enduring power is as a work of fiction, according to Boruch Gorin, editor-in-chief of Knizhniki, the Moscow-based publishing house of Jewish books.

“That masterpiece put me inside the story,” he recalled in a phone conversation.

Gorin first read the book in 1992, when he was 18 and 50,000 copies of a one-volume edition of the first two novels, titled “Herbert and Nelly,” were published in Moscow. The book sold out almost immediately and was long-listed for the 1993 Russian Booker Prize.

As a work of literature, “Herbert and Nelly” exposes the characters’ inner struggles as well as the historical landscape that comes alive in a much more powerful narrative than works of nonfiction, Gorin said.

Gorin’s original copy still holds an honored place in his library, he said.

In 2014, his publishing house brought out a revised two-volume edition of “Herbert and Nelly,” a chance for newer generations to read the book, he said.

Born in 1936, to a Jewish family in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg), David Shrayer (he later took on the pen name of David Petrov, now hyphenated), grew up a descendant of generations of Lithuanian rabbis and millers from the Podolian region of Ukraine. Through these older generations, he was exposed to Jewish culture and traditions and to Yiddish. He came of age amidst the openly anti-Semitic campaign of Stalin’s last years, an experience that sharpened his sense of Jewish pride, according to his son.

In the novel, the character of Doctor Levitin comes reluctantly to the decision to leave his country. In his own life, the decision to emigrate was not easy, Shrayer-Petrov acknowledged, a tearing-away from the foundation of his life, its culture and the language of his artistic output.

His love of music, formal vocal training and deep knowledge of 20th-century Russian composers echo on the pages of “Doctor Levitin,” with bursts of staccato-like phrasing juxtaposed with melodic passages describing the landscapes of the Russian countryside.

“I am happy you found this in my book,” Shrayer-Petrov said, noting that among his papers and letters is a brief correspondence from the 1950s with Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich. The two discussed the possibility of collaborating on a musical production based on the works of Soviet poet Vladimir Mayakovsky, Shrayer-Petrov recalled.

Looking back, Shrayer-Petrov is grateful that as an emigre, he was able to continue both of his life’s pursuits in medicine and literature. Among his English language works is the 2014 collection, “Dinner with Stalin and Other Stories,” that includes short fiction about Russian Jewish immigrants living in the U.S.

Today, he and Emilia Shrayer are proud grandparents of two American-born, bilingual girls, and he considers himself a Russian-American-Jewish writer, settled in his life as a New Englander.

Despite some health problems, Shrayer-Petrov is excited to be assembling a volume of his collected poetry and working on a new novel.

“I have the possibility to continue to write in freedom,” he said.