These days, the August light begins to hint at the upcoming Days of Awe. The first part of Brian Platzer’s engaging first novel, “Bed-Stuy Is Burning” (Atria), is titled “Rosh Hashanah,” and most of the action takes place on the holiday, but far from any synagogue. As the story unfolds in a cinematic style, themes of self-reflection, repentance and new beginnings emerge.

This is a novel of New York’s streets, set in Brooklyn, at the intersection of race, culture, class, religion and real estate.

In Bed-Stuy — as the neighborhood of Bedford-Stuyvesant in north-central Brooklyn is known — tensions just-below-surface between newcomers and old-time residents, wealthy folks and those being displaced by gentrification, are erupting into violence. The spark is the police shooting of an unarmed 12-year-old boy.

The characters whose lives collide on one block of 19th-century brownstones are a varied lot of New Yorkers, including a homeowner born in Georgia and single father to his angry son, a college professor who connects with his army veteran brother over their interest in guns and a Christian woman beginning to cover her hair in Muslim tradition as she feels pulled toward Islam and reads Jewish religious books in the home of her employers. She’s the babysitter for the only white couple that owns a home along the row of Victorians: a rabbi-turned-Wall Street banker and his girlfriend, a journalist who is more ambitious and serious-minded than the pointed celebrity profiles she writes. They have a newborn son. Former Police Commissioner William Bratton has a role too, as does a high school dropout who spends much of the novel trying to camouflage the pair of handcuffs linking her arms.

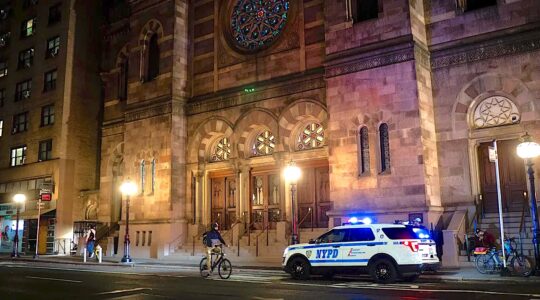

The story is told through their varied perspectives. At the center is Aaron, who was a top student in his rabbinical class and landed a first job at a prestigious Upper East Side synagogue. All eight of his great-grandparents were murdered in the Holocaust and he “felt he owed it to the history of his family” to serve and redress the horrors they faced. But he lost his faith, and consoling others became complicated. And then he lost his job, surrounded by shame. When he’s interviewed for a position at an investment firm, he is asked few questions and goes on to succeed there. For him, “Bed Stuy was the best bet he’d ever made,” a thrilling risk he took in the feverish real estate market; he was already earning back on his investment after the first year.

In protest against the shooting of the young boy, a quick series of events, beginning in the subways and continuing to a schoolyard to the streets and then to the inside of Aaron’s home, ignites the neighborhood. Platzer’s portraits propel the gritty and nuanced narrative. Along the way are dramatic turns, love stories and moral quandaries.

“I realized that I didn’t have an answer; I didn’t have a legislative solution to any of this. So I felt a more useful and honest way to process the issues surrounding gentrification was through fiction.”

The novel grew out of the author’s life. In an interview in Manhattan, he explains that he and his wife moved to Bed-Stuy about seven years ago from another Brooklyn neighborhood. When they found a home dating back to the 1890s, with original stained glass and woodwork intact on a tree-lined street, they figured they could purchase the place, rent out two apartments and have space for the family they were planning. They are still the only white homeowners on their block. It took a couple of years to make friends, but now their neighbors look out for their two young sons.

“This has been a spectacular place to live,” Platzer says, but admits that at first he was “foolishly naïve” about others’ attitudes toward gentrification and gentrifiers, like his family.

Commuting to his job in Greenwich Village where he teaches World Writers at Grace Church School, he would notice kids not much older than his eighth graders being handcuffed, and began to wonder about what might happen if things ratcheted up. As he imagined the reality of his world, he began doing research about racial incidents and interviewed neighborhood residents as well as police officers. Outside a local school, he used his experience talking to middle and high school students to get these kids to open up about their own experiences.

“I thought about writing an op-ed piece,” he says, “but I realized that I didn’t have an answer; I didn’t have a legislative solution to any of this. So I felt a more useful and honest way to process the issues surrounding gentrification was through fiction.”

“One of the reasons I made the protagonist a lapsed rabbi is that realities between Jews and blacks are so fascinating and complicated over the last half century,” he says. “I was excited to discuss faith in Brooklyn, the borough of churches, where church on Sundays is such a prominent element of neighborhood life.”

“One of the reasons I made the protagonist a lapsed rabbi is that realities between Jews and blacks are so fascinating and complicated over the last half century…”

If there is a synagogue for the newcomers to Bed-Stuy, he doesn’t belong. His own Jewish life is still centered in Greenwich Village, where he grew up, and he attends East End Temple. When he was young, his family attended another shul where, soon after Platzer’s bar mitzvah, the rabbi mysteriously left the congregation. He says they were never told why, although there were many rumors.

Support the New York Jewish Week

Our nonprofit newsroom depends on readers like you. Make a donation now to support independent Jewish journalism in New York.

“I spent a lot of years thinking about it — how an upstanding leader of his congregation might find that leadership deteriorating. It was an abrupt and bizarre catalyst of my religious coming of age.”

As part of his book tour, he’ll be addressing Jewish audiences, and he says, “I am giddy to discuss issues of Jewish history, Jewish morality, whether faith is necessary for a Jewish life, and how those questions become political questions in our current day and age.”

“I don’t feel I could have written this book without a Jewish upbringing — the focus, on one side, on textual analysis that is in some ways inherent to Jewish life, and on the other side, a moral awareness that is equally inherent; it enables me to think through these issues in a way that I feel very indebted.”

He says that all of his characters are driven by an honest selfishness in the moment, with all looking out for themselves and their own families. His hope was to create people who are “recognizably human if not always likeable.” He understands that some might say “it’s impossible to write from the perspective of people whose own experience is disparate from your own” and that it’s “immoral to financially benefit from it.” But for Platzer, writing is an exercise in empathy.

“It’s my vision of art that it’s very important for an artist to try to imagine your way into other people’s experience.” His writing is full of compassion.

While he is very sympathetic to the Black Lives Matter movement, he acknowledges that he has been insufficiently involved. “For a while I’ve been hiding behind writing this novel as a performance of civic duty. Now I think it’s important to do more.”

“It’s my vision of art that it’s very important for an artist to try to imagine your way into other people’s experience.”

Platzer has published articles, humor pieces and personal essays, including a candid essay last year about a neurological disorder he suffers from, which has been difficult to diagnose and treat; his migraines manifest as constant dizziness. He had to take a year off from teaching and worked through the pain to compete the book. While his condition is better and he will return to work in the fall, he still deals with dizziness.

In a powerful scene in the novel, the lapsed rabbi delivers an impromptu sermon on his doorstep, and, in the midst of violence, holds the crowd of rebelling kids and upset neighbors with his words.

Asked whether he ever considered the rabbinate, he says, “I would love to be rabbi, to be a useful member of a tight community. I’d love to read the Bible and discuss it; I’d love to help people who are struggling with life’s difficulties. But I don’t have the unshakeable faith that seems a prerequisite.”

The novel, like its author, is filled with questions. The second part, after the streets are again calm, is titled “Days of Awe,” as new possibilities are ignited. n

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.