Even 60 years later, Philip Bialowitz of Queens is haunted by the Nazi killing factory at Sobibor, Poland.

"I still have sleepless nights," Bialowitz, 74, confides. "I still see the killings. You could see the smoke miles away. They killed my two sisters and a niece at Sobibor. My niece was 8 years old and knew she was going to die."

He says that when he first arrived at Sobibor, someone asked if he came with his family.

"I said yes," Bialowitz, of Little Neck, recalls. "He said, ‘Turn around, this is your family.’ He pointed to the smoke."

And Bialowitz says he cannot forget a woman, while her hair was being shorn, asking: "How long will it take to die?"

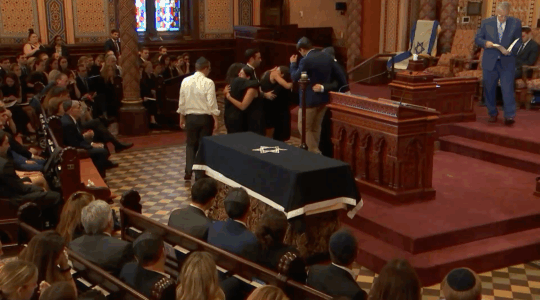

Bialowitz plans to return there this weekend for memorial ceremonies marking the 60th anniversary of the revolt at Sobibor, when the Jewish inmates turned on their Nazi captors, killed many and ran into the woods on Oct. 14, 1943.

Six hundred of the inmates fled; 140 were killed during the escape, another 160 were caught a short time later and executed. The remaining 300 managed to elude the landmines that surrounded the camp and the bullets fired by Nazi guards and made it deep into the forest. It was the largest successful escape from a Nazi death camp.

But only 48 survived the next year, during which the war ended. Many of those who didn’t make it were killed by their former Polish neighbors. Bialowitz and his brother Simcha, 92 and a resident of Holon, Israel, are two of only eight who survive today.

Reflecting on his escape, Bialowitz says he has lived his life fulfilling the wishes of one of the escape organizers, Sasha Perchersky. The Russian Jewish prisoner of war had told his fellow inmates: "If by chance someone should live and escape, he should remember that it is his duty to be a witness and to tell the world about this place and what happened here."

Perchersky had arrived with other Russian Jewish prisoners from the Red Army in September 1943. A lieutenant and leader of the Russian troops, he and the camp’s resistance leader, Leon Feldhendler, planned the escape. It involved killing the key Nazi leaders in just one hour (luring them to workrooms with a promise of expensive leather coats and boots left behind by recently gassed Jews) and cutting electric and telephone lines.

In making his escape through the barbed wire that ringed the camp, Bialowitz cut his left forefinger. He still has the scar.

He had been at the camp about six months performing a variety of jobs. One of them was helping newly arrived Jews off the cattle cars on which they arrived. Some of them offered him tips as he helped them with their baggage.

Bialowitz was assigned also to go through the luggage and clothing of the Jews and retrieve jewelry and other valuables. But Bialowitz says he threw 90 percent of the jewels down the toilet and buried two jars at the foot of a nearby tree.

After the war, Bialowitz remained silent about his experiences. But about 10 to 15 years ago, he said he began speaking to school groups and organizations about what happened for "fear that nobody would be left to tell the story."

He also went back to Sobibor in the late 1980s to retrieve the jewels for a documentary film, "Hunt for Stolen War Treasures." But the area already had been dug up by "Polish peasants" searching for valuables that had been left behind. The movie crew also found that a cemetery several miles away in Izbica had been similarly dug up. It was there that Bialowitz found bones and a skull that had been disinterred by people looking for treasure.

"I was shocked that the people couldn’t even be left to lie in peace," he says. "And one of the Polish townspeople told me my mother was shot there with 60 other people. He then gave me a skull that had been lying in the cemetery and said, ‘This could be your mother.’ I got very emotional."

When he speaks to audiences, Bialowitz says most people are "very shocked to hear" what happened at Sobibor. He insists that people bring their children to hear him speak.

"They have to perpetuate the story of the Maccabees of Sobibor," he says.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.