The empty storefront on Broadway at 84th Street, where Morris Brothers stood, is haunting — in more ways than one.

Neon posters advertising the opening of a costume superstore, just in time for Halloween, are plastered across the windows of what used to be the storied Jewish-owned sportswear shop, a fixture of the Upper West Side for more than 60 years.

The closing of Morris Brothers this summer, in part due to a more than 50 percent rent hike, marks not only the end of buying nametags and camp gear in a non-gussied-up environment, but also the near finality of an era in which family-owned stores thrived and shop owners referred to customers by name.

And the closing is contributing to the slow erosion of a hard-to-define but unmistakable Jewish character that helped make the Upper West Side what it is.

“It’s really a shame,” says Peter Koch, owner of Town Shop, the famed lingerie store first opened in 1888 by Koch’s grandfather, located two blocks from Morris Brothers. “But when rent jumps to more than $1 million a year, imagine how much business you have to do to pay that.”

Morris Brothers is but one of the most recent casualties of the “bankization” of the Upper West Side, as Council Member Gale Brewer put it. With North Fork Bank, Victoria’s Secret and Duane Reade taking over storefronts along Broadway, the independent grocery stores, cleaners and hardware stores are being squeezed out. Building owners would rather rent to chain stores, since the mom-and-pops have a harder time affording the ever-rising rents.

“You can’t find a shoemaker, and you have to almost hunt for a store that has a tailor,” Koch says, sitting at the register in front of a “Who needs Bloomingdales?” sign pasted to the wall. “This neighborhood used to be filled with these kind of stores. Now, there are no little shops, just flagship stores.”

Indeed, boutiques are scarce along Broadway. Liberty House, a women’s clothing shop located in the 80s, just shuttered its doors. More than a year ago, Judaica Treasures, on West 72nd Street, closed. In June, The Jewish Week reported that skyrocketing rents could force West Side Judaica, the only Judaica store remaining on the Upper West Side, to board up shop. And Makor, the edgy Jewish cultural center, has abandoned the neighborhood in favor of trendy Tribeca, where it will open next year.

While the Upper West Side is still decidedly Jewish, something of its mom-and-pop, neighborly Jewish character has been lost. In its place: banks, and lots of them. Sixty-three, to be exact. Brewer, who represents the Upper West Side and Clinton, has been keeping track of the number of banks infiltrating the neighborhood, spanning 54th Street to 96th Street, from the Hudson River to Central Park West. “That, to me, is an astonishing number,” says Brewer, noting that bank proliferation didn’t exist when she was elected in 2002. “It’s gotten out of control.”

Earlier this month, Brewer hosted a hearing with Council Member David Yassky, chair of the Committee on Small Businesses, aimed at developing solutions to ease the burden on New York City’s 186,000 small, family-owned businesses — many of which are struggling to survive.

Brewer’s three-pronged plan includes tax cuts for small businesses, zoning restrictions that would limit the size of storefronts and require banks to occupy the second floor, and streetscape improvement. Her biggest gripe is the Wachovia branch located on Broadway and West 85th Street. “At night it’s so bright,” she says. “You feel like you’re in ‘Star Wars.’” In fact, the kind of sterile sleekness Brewer describes seems to be taking over the neighborhood.

Brewer has tried contacting the building owner who raised West Side Judaica’s monthly rent from $8,000 to $18,000 in May, but to no avail. “He won’t answer my calls,” she says. Other building owners she’s spoken with say they’re not discriminating against small businesses, they just want to bring in revenue and don’t care whether another Duane Reade or bank springs up.

West Side Judaica’s owner, Yaakov Seltzer, says his situation is “month to month,” but he adds that pleas from Upper West Side rabbis for their congregants to patronize the shop have revived business somewhat. “I’ve seen customers I haven’t seen in years,” he says.

In the past decade, along with the influx of Modern Orthodox Jews, the Upper West Side has become more affluent. The demographics have shifted, with a majority of residents working in finance or other professional fields, according to U.S. Census data. As the neighborhood grew richer, banks swarmed in like ants and swankier retailers like Godiva set up shop.

The Upper West Side “used to be a Jewish man’s Greenwich Village,” says “The Golems of Gotham” author Thane Rosenbaum, whose novels are all set on the Upper West Side, where he currently lives. “Broadway used to be a Jewish cultural domain, teeming with cafeterias and filled with poets, writers, socialists and schoolteachers.”

Now, he says, it’s become a mall. “It lost a lot of its progressive, liberal, artistic charm,” Rosenbaum says. “Now it’s filled with moneyed, real estate-obsessed, 401(k)-obsessed people who are more concerned with renovating their kitchens than discussing ideas. It’s still incredibly Jewish, but the mindset is different.”

This changed outlook is reflected in the physical reality: There’s a bank on every corner and an increase in residential housing, but few cafes, delis or grocery stores. And no bakery.

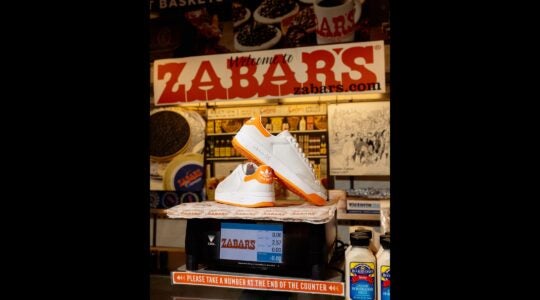

That’s what Sol Zabar, owner of the famed appetizing store, Zabar’s, misses most. “No one is doing the baking,” Zabar says. “The young ones don’t want to get up at two in the morning to go bake through the night.” He reminisces about days past, when Jewish-styled restaurants like the Tip Toe Inn were still around.

Even the simple act of fixing a watch requires careful sleuthing to find that lone jeweler who’s still in business.

Zabar, who has lived within 10 blocks of his store since he was 6 years old, has seen the face of the neighborhood shift throughout the years. “It’s a generational change,” he says. “The people running these businesses were Europeans who worked hard and put in the time. Their offspring, however, went in a different direction. They got old and retired and the businesses died out.”

Morris Brothers was one of the last. “The so-called mom-and-pop stores are disappearing,” says Zabar. “The problem is that rent has appreciated in the last two years.” Zabar’s, however, is here for the long haul, he says. Since he owns the building on 80th Street, rent woes don’t plague him.

Not all business owners are so lucky. Elena Torres, the owner of Toscana Shoe Repair, a small storefront wedged between conglomerates, says her rent has increased approximately 50 percent during the last five years. “I’m working harder,” she says. To maintain a competitive edge, Torres focuses on offering a high level of customer service, including free delivery.

At Upper West Side Copy, a small copy shop only blocks away from Kinkos, customer loyalty is built by filling orders on the spot. “It’s the one last place that’s not a bank,” says Lee Green, who has been working the counter for 10 years.

“This homogenization effect is not unique to the Upper West Side,” says Rosenbaum. “But there was a distinctiveness and quirkiness to the Upper West Side. We always believed it wouldn’t happen here.”

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.