The new 10-year study of the Jewish population of New York presents a major challenge to UJA-Federation, which commissioned the survey, because the research indicates that our community is moving sharply in two opposite directions: very engaged Jewishly (but not necessarily communally) and decreasingly interested in Jewish life.

Thirty-seven percent of the respondents describe themselves as “Just Jewish,” suggesting for the most part that they are not involved, and another one-third are Orthodox, with the largest segment of them haredi (or, ultra-Orthodox), known more for separating themselves from other Jews than connecting with them.

And it’s the Orthodox community that is keeping our numbers from declining. While Orthodox Jews now make up 32 percent of all Jews in New York (compared to 13 percent nationally), 64 percent — that’s almost two-thirds — of all Jewish children in the eight-county area are Orthodox.

So how does the federation, which seeks to identify, serve and strengthen the Jewish community, respond — not to mention fundraise — when so many of its constituents appear to be so disconnected from its efforts?

Compounding the challenge is the fact that poverty rates are on the rise with more than 500,000 Jews — about one in four — living in poor or near-poor Jewish households in New York.

How do you meet the rising needs when your core constituency is in serious decline?

There are no easy answers, but one thing this new study suggests is that we need to rethink the definitions of “Jewish community” and the goals and strategies of those committed to serving it.

One person close to the study described the challenge bluntly, noting that federation represents “the center” of the community, and in light of the new findings, “we don’t know where the center is.”

Indeed it seems that the middle has fallen out of our community while the “wings,” as one sociologist says, are growing rapidly.

For example, while the percentage of Orthodox and non-engaged segments are on the rise, the Conservative and Reform movements have decreased by about 1 percent a year since the last New York population study a decade ago. They have each lost 40,000 members.

Diverse, Fluid, Complex

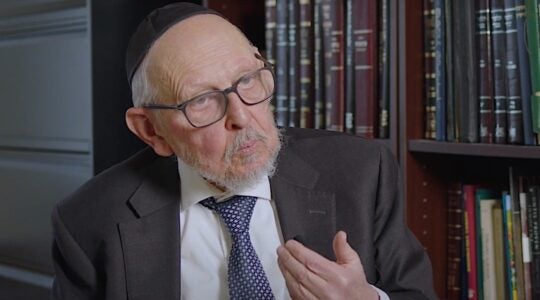

But Steven M. Cohen, a leading sociologist and one of the three authors of the study, points out that the notion of a society with a strong center is passé, and that over the last several decades America has become increasingly diverse, fluid and complex.

“We are long past the 1950s America of Mom and Dad, two kids, the suburbs, and the dog in the backyard,” he said in an interview, noting that the New York study of 10 years ago already found signs of increasingly individualized identities on the rise among Jews.

The new study offers “a sharper picture of diversity,” according to Cohen, with more Jews in both the highly engaged and highly unengaged sectors, reflective of an American society in general that is “more diverse, more of a mosaic and with more complexity.”

The growing religious polarization in the United States in recent decades reveals an increase in both the Evangelical movement on the right and among secular liberals on the left, for example, and a decrease among religious moderates. The same holds true in the Jewish community, with haredim analogous here to Evangelical fundamentalists on the rise, and Reform and Conservative Jewry offering a parallel to mainline Protestants, whose numbers have diminished.

Cohen said he was personally surprised by the large numbers of Jewish poor in the study and by the “enormous complexity” of a Jewish community today whose households contain so many variations of Jewish identity, in part the result of decades of significant intermarriage rates.

He recalled one respondent to the survey who said she was Jewish when she was with her father and Christian when with her mother, reflecting “the fluid boundaries of American Jewry, with more intermarriage and more people identifying as partial Jews.”

The study found the intermarriage rate to be 22 percent, the same as in 2002, but 40 percent overall among the non-Orthodox, and a new high of 50 percent among non-Orthodox couples married in the last five years.

One critical issue these statistics underscore is the pivotal role of the Modern Orthodox community. Will it seek to protect itself by turning inward, away from a community it sees as a potential threat for moving further from Jewish tradition? Or will it view its role as a bridge, and seek to foster Jewish peoplehood by becoming more actively involved in Jewish communal life, with all its attendant risks?

Over the last several decades the Modern Orthodox have moved to the right, in part a result of young people coming back from a year or two of post-high school yeshiva study in Israel and taking on more stringent levels of observance than their parents.

But there are those of us within that community who argue that for the sake of klal Yisrael and Jewish unity, halacha should function as more of a gateway than a barricade on issues from communal participation to conversion.

The question is how far religious parameters can be stretched for the sake of harmony when divergent views grow farther apart about what it means to be a Jew.

UJA-Federation can help by recognizing the diversity and nuances within the Orthodox community itself, with the three largest groups self-identified as chasidic, yeshivish (together characterized as haredi) and Modern Orthodox, and by further deepening its role in dealing with issues of particular concern to the Orthodox, primarily the increasingly prohibitive cost of day school education.

The notion that “the Orthodox can take care of themselves,” prevalent among a number of influential philanthropists, is seen as dismissive and untrue in the Orthodox community.

Responding Takes Time

Patience is required of all those who expect immediate outcomes to the problems posed by the survey’s findings.

“It’s seductive to think that once you have the data you have the answers,” noted Alisa Kurshan, senior vice president of UJA-Federation, “but data is the point of departure.”

She pointed out that it has always been the job of the federation to bring together, and serve, diverse communities within the larger Jewish community, and that it intends to do so now as well, though it takes time “to analyze the new information and determine how philanthropy can have the most impact.”

She noted that the community responded to the rise in intermarriage two decades ago by launching programs like Birthright Israel and founding new community day schools. Similarly, when it learned 10 years ago of the significant increase in Russian-speaking Jews here, efforts were made to integrate them into the mainstream. These include the establishment of COJECO (the Council of Jewish Émigré Community Organizations), a coordinating body in the Russian Jewish community, a summer camp for children from Russian-speaking families, and a leadership program for those in the Russian Jewish community, co-sponsored with the Wexner Foundation.

“Some may say it takes too long, but it happens,” said Kurshan.

Anticipating communal reaction to the study, John Ruskay, the executive vice president and CEO of UJA-Federation, observed that “no doubt elements of this report will be uncomfortable for many, if not most, who hold it up as a mirror.”

But he expressed confidence that UJA-Federation and the Jewish people “can find ways, while respecting differences, to strengthen the whole Jewish community and people.”

He asserted that the key to Jewish continuity revolves around identity, observing that if a person does not identify Jewishly, “why would he care about a poor Jew in Brooklyn or Kiev, or supporting the Jewish state, or helping people who want to settle in Israel?

“Identity is the driver of everything we care about,” he said.

In the end, then, it still comes down to fostering and strengthening a positive Jewish character in what some are calling a “leaner and meaner” American Jewish society where fewer people affiliate, but those who do are more intensely involved.

Among the many questions raised by the new study is the primary one: can enough of a core be maintained, cultivated and strengthened so that Jewish peoplehood remains a goal and reality rather than a quaint phrase that will fade from our vocabulary?

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.