When I was in seventh grade I ran for president of our community-wide youth investment club. Investment clubs were common in the 1950s and `60s in the adult world, and parents encouraged their kids to learn the value of financial investing early. What I learned from my experience in the club changed me, but not the way my folks intended.

I had never been the president of anything. I deeply wanted the position, but more for the achievement of popularity and less for the goal of making money for my friend and me. I wanted the presidency so badly that at the closed ballot election my competitor and I “jokingly” agreed to vote for each other. He voted for me –and I voted for me. I won by a landslide, but the victory was ash in my mouth. My feeling of guilt for betraying Joey, my opponent, was so deep that I apologized publicly and asked for a re-vote. But because an overwhelming majority had voted for me anyway, the group let the vote stand. I served my term and everyone else probably forgot the incident. But disappointment in my own behavior at the age of 14 and the worthlessness of the victory that resulted has not diminished in nearly 50 years. Whenever I really truly want something I first see Joey’s image. There is nothing worth getting at any cost if the cost is your soul.

Pretty dramatic for a seventh grader. But some of us, even rabbis and political leaders, aren’t lucky enough to have had this experience as children. Sometimes it happens in adulthood, when the consequences are far more serious.

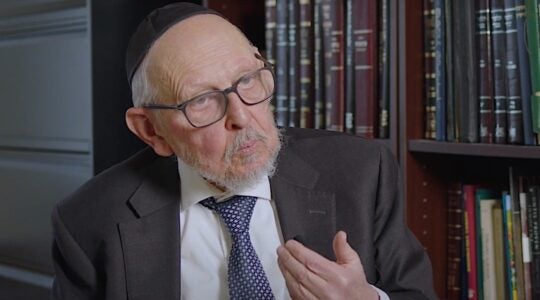

As I’ve read the news reports about my colleague Rabbi Michael Broyde, former head of the Rabbinical Council of America’s Beit Din — he has admitted writing academic treatises supportive of his own positions using an assumed identity– I have been deeply troubled. Such actions are indefensible in a leader of any kind, let alone a rabbi.

Yet I can’t help thinking that while some will gloat at the almost silly manner in which he self-destructed, the rest of us face a deeper challenge. I have had the opportunity over the years to be in touch with Rabbi Broyde. I have had differences of opinion with him and have been disappointed in decisions made by his court, particularly those that left serious converts to Judaism bereft of community.

At the same time, there is no doubt in my mind that he remains an excellent scholar of Jewish law with a sharp mind. We rabbis, scholars of Jewish law and laymen committed to the ongoing development of halachah, have to decide if, at least in the case of Rabbi Broyde, his solid legal scholarship is to be henceforth ignored. If it is true that no one was damaged by his behavior other than himself, I propose that Rabbi Broyde’s scholarship should not be dismissed along with his behavior. Surely he has no business in communal leadership. But if Richard Nixon and Bill Clinton could be rehabilitated to leadership after deep-seated moral failures, surely Rabbi Broyde’s halachic work deserves consideration in the world of Jewish law, even if he himself does not.

I am sure that the lessons learned from his fall because of the childish need to be great and right have hit Rabbi Broyde even more deeply than my seventh grade ethical failure hit me. I hope that once the dust has settled, the scholarly work he has done for the sake of Torah and the Jewish community at large will not be red-lined because of his failure of leadership.

We are told in the fourth chapter of tractate Berachot that Rabbi Nechuniah ben HaKaneh used to say a brief prayer when he entered the House of Study (to teach) and when he left. When queried about its nature he said: “When I enter I pray that no calamity happen at my hand and when I leave I give thanks for my portion.” For Rabbi Broyde, calamity has happened at his hand, hopefully only for himself and no one else. If so, I pray that we will not compound the calamity by ignoring the positive value of his work.

Rabbi Ronald D. Price is executive vice president emeritus of the Union for Traditional Judaism, and dean emeritus of the Institute of Traditional Judaism.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.