Thankfully, the recent controversy at Yeshiva University over a rabbinical student who had held a private “partnership minyan” in his home has been resolved satisfactorily, and hopefully without harm either to the student or to the critically important institution that he attends. Cooler heads, fortunately, have prevailed. Yet the fact of the controversy itself raises broader questions concerning the future directions of Modern Orthodoxy and its role within the American Jewish community.

Modern Orthodoxy generally dates its origins to 19th-century Germany and its rabbinic leader Samson Raphael Hirsch. Rabbi Hirsch argued for upholding the integrity of Jewish law in contemporary society. Nonetheless he embraced modern culture in so-called “neutral” areas — dress, politics, secular education — in which personal conscience could prevail. To be sure, some on Rabbi Hirsch’s left criticized this approach as bifurcating Torah values and general cultural norms and called instead for a distinctive synthesis between these two very different value systems. Nonetheless, Rabbi Hirsch departed sharply from haredi Orthodoxy, whose leaders argued for “Daas Torah,” meaning that all questions — halachic or extra-halachic — must be submitted to Talmudic authorities whose views were binding. For example, the latter generally rejected secular culture save for utilitarian purposes of earning a living.

It is in this context of what constitutes “modern” and what constitutes “haredi” Orthodoxy that the recent rabbinical student controversy carries great significance. In the fall of 1977, Yeshiva University appointed a new dean of its Division of Communal Services and convened a symposium of its rabbinical alumni to mark the occasion. Featured speakers were the renowned social scientist Charles Liebman and the acclaimed philosopher David Hartman, both of blessed memory. Each spoke brilliantly and critically on trends within contemporary Orthodoxy. In closing the symposium, the incoming dean added an astute observation: He noted the growing trend for local rabbis to issue rulings, which congregational laymen then appealing to their roshei yeshiva, who in turn felt free to overrule the local rabbi.

Dean Vic Geller declared that he and his colleagues were determined to reverse that trend. Presumably they realized that the trend was rooted far more in the culture of the haredi world than in the Modern Orthodox communities they were determined to enhance.

Unfortunately, the recent controversy suggests that the precise opposite has occurred. The letter to the student issued by the acting dean of Yeshiva’s rabbinical school, Rabbi Marc Penner, suggests that local rabbis do not possess such authority. All questions, in his view, must be submitted to roshei yeshiva for adjudication. Presumably these men, albeit far removed from local conditions and needs, are more qualified to issue pronouncements, and their views must be considered binding.

Remarkably, Rabbi Penner extends this mandated process to “areas of established Jewish custom and public ritual … even when there are no purely Halachic issues at stake.” To take this logic to its conclusion, the local rabbi must consult respected Talmudic scholars before taking the liberty of inviting public officials or guest scholars to address the congregation. Similarly, if a rabbi wishes to compose a sermon based on Jewish historical experience, theoretically he need consult not the history books but the Talmudic scholar!

Why is this significant? First, demographically, Orthodoxy is on the rise in American Jewry today. It can contribute enormously to enriching Jewish life. Yet an Orthodoxy governed so narrowly will only prove alienating to so many who stand to learn from it. Leaders of partnership minyanim found sanction for their practice among halachic authorities — not the ones referenced in Rabbi Penner’s letter but others of impeccable scholarly credentials. They merit communal support rather than condemnation for their efforts to synthesize tradition with modern culture.

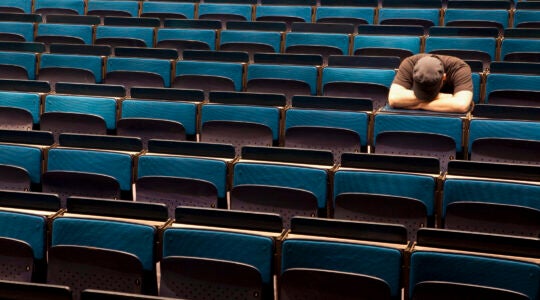

Second, Orthodox leaders, like all Jews, must confront the reality, documented by the recent Pew Research Center report, that assimilation poses our single greatest danger. Currents and movements that enable Jews to connect more seriously with Judaic tradition deserve encouragement. Orthodox rabbis open to exchange and dialogue on these issues have the opportunity to play a most constructive role within Jewish communities. By contrast, Orthodox rabbis who segregate themselves from such currents may well find themselves alone in a “purist” Orthodoxy acceptable to their roshei yeshiva, but not to the broader Jewish community.

Last, professor Liebman, while teaching at YU decades ago, argued that freedom within the haredi world meant consulting the “gedolim” or Talmudic authorities. That definition of freedom admittedly possesses the virtues of consistency and clarity of direction. Prof. Liebman noted, however, that the wisdom of the gedolim on the major questions of Zionism, immigration to the U.S., and secular education had been proven wrong by history. By contrast, Modern Orthodoxy treads a far more difficult path of seeking both to preserve rabbinic authority yet constrain that authority so as to allow for intellectual freedom and expression of diverse viewpoints. Modern Orthodox leaders today may choose to engage modern culture and thereby exercise leadership on the critical questions of gender equality, conversion to Judaism, Jewish education, intra-Jewish relations, and the challenges of contemporary biblical scholarship to traditional faith, to say nothing of Israel’s future as a Jewish state.

Alternatively, they may opt to shelter themselves in the cloister of an Orthodoxy far removed from the social and intellectual currents of modernity. My hope is that Modern Orthodox leaders will opt for the former course. My fear is that the latter course will prevail, to the detriment of the collective Jewish interest.

Steven Bayme is national director of the American Jewish Committee’s Contemporary Jewish Life Department.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.