My colleague Rabbi Elliot Cosgrove's wonderful essay in The Jewish Week ("All A Rabbi Can Command These Days Is Respect," March 28) got me thinking even more deeply about the question of freedom of the pulpit and the responsibilities that come with it: What is the rabbi’s role in addressing controversial issues, be they matters of public policy generally, or Israel specifically?

As we make our way through the book of Leviticus, in Hebrew Vayikra, “And God called," we know that every rabbi hears God’s call, perceives his or her role on such things, differently. I believe that congregants want to be engaged from the pulpit on topics that matter. And I believe that with thought and study, a rabbi can be provocative without being alienating. Addressing sensitive issues demands sensitivity: to the variety of perspectives present within our tradition and to the diverse opinions held by one’s listeners. Nonetheless I do believe passionately that rabbis have a duty to lift up the lens of Jewish tradition through which others might view the critical events of our time, and then to say what they think. Without the confidence to do that, a rabbi cannot provide the moral leadership the role demands, or command the respect the role deserves.

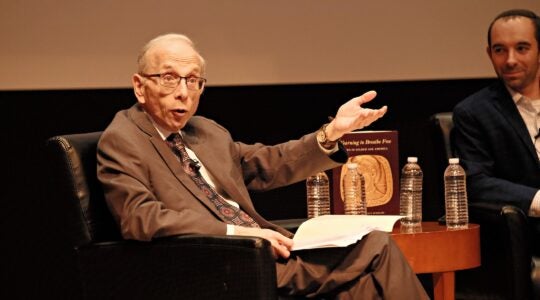

The exemplar of such a rabbinate was the giant of American Jewry, Rabbi Stephen S. Wise, whose early fame came after an encounter at my congregation, Temple Emanu-El, which Rabbi Dr. Ronald Sobel describes in his synagogue history as nothing less than “legendary."

In 1905, the temple’s board of trustees was considering Rabbi Wise as a potential co-rabbi with Dr. Joseph Silverman, and invited him to come east from his pulpit in Portland, Oregon to deliver three trial sermons. Now Rabbi Wise was not a fan of Emanu-El, and almost certainly would not have accepted the position had it been offered. But that did not prevent him from taking full advantage of the opportunity to raise, in a very public way, his views about freedom of the pulpit. In a sermon titled, an “Open Letter” to the Trustees of Emanu-El which he released to the press, Rabbi Wise wrote: “If I am to accept the call to the pulpit of Temple Emanu-El, I do so with the understanding that I am to be free and my pulpit is not to be muzzled…. The chief office of the minister…is not to represent the views of the congregation but to proclaim the truth as he sees it." In fact, freedom of the pulpit had not been an issue at Emanu-El, nor has it been. Rabbi Wise chose to make it one to drive home to the wider Jewish community his belief that a rabbi cannot lead without an unfettered freedom to speak. (Ultimately he did come back to New York to found the Free Synagogue on the West Side.)

To borrow a phrase from Rabbi Wise, rabbinic leadership demands the courage to call it "as we see it."

But it demands something else too. A comment on Vayikra is instructive. Leviticus deals at length with sacrificial worship. Its opening verses begin Adam ki yakriv mikem korban l’Adonai, “an individual who brings from yourselves a sacrifice to Adonai.” Grammatically inconsistent, the clause moves from the singular to the plural. The Sefat Emet drew an important lesson from that inconsistency: It implies, he taught, that when one brings an offering, one must consider oneself as part of a greater people. In other words, whatever we offer “of ourselves” must take into account the needs of all Jews. For rabbis, our words are our offerings. So when we speak out we must ask ourselves, what is it that we as individuals believe, and what is it that the Jewish community needs said?

When it comes to the welfare of Israel and of our people, rabbinic leadership requires an awareness of where all those listening (inside our congregations but especially outside them) stand and what they know. To whom we speak must guide what we say. No doubt this could be said about a host of concerns, but I certainly believe it true regarding Israel. Right now, I believe the Jewish community needs us to offer our honest criticisms of Israel if we are so inclined, but always from a place of love, and always in a way that conveys the true complexities of the Mideast conflict and the dangers to Israel – not only for the benefit of those Jews who don’t grasp them, but for the wider non-Jewish world which listens so very closely to — and indeed respects — what we say.

Rabbi Joshua M. Davidson is the senior rabbi of Congregation Emanu-El of the City of New York.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.