Some people might think that facing the challenging reality of intermarriage and being fully committed to Orthodox Judaism is an oxymoron. Yet, two weeks ago, 20 Orthodox rabbis accepted an invitation by Big Tent Judaism and the Lindenbaum Center for Halachic Studies at Yeshivat Chovevei Torah to join together for a behind-closed-doors, daylong symposium focused on the nexus of the two issues.

We promised no media coverage out of respect for the rabbis’ willingness to participate. Sponsored by the Marion and Norman Tanzman Charitable Foundation, this was a historic meeting for Orthodox rabbis — the first of its kind — since the focus was not on so-called prevention. Rather, it was about understanding intermarried couples and their families. The conversation was frank. There were no pulled punches. Yet the pervasive question taken up by these rabbis was: How do I connect with people whose life choice I disagree with — and keep them engaged in the Jewish community?

While it is common wisdom that intermarriage does not impact the Orthodox community, these rabbinic leaders know that this is not the case, even if the incidence of intermarriage in the Orthodox community is far lower than among other population segments in the community. Thus, all those in attendance took a bold step forward into American Jewish life by attending the symposium and digging deeply into the issues, knowing full well that they could help shape the future landscape of American Jewish life by how they respond to intermarriage in their communities and beyond.

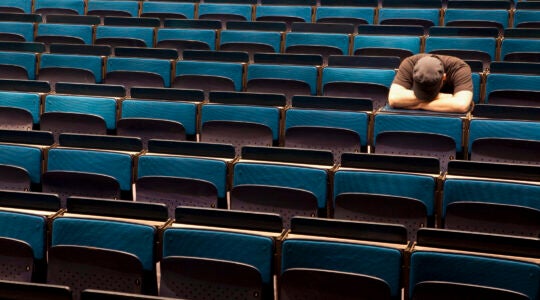

It is unfortunate that the Jewish community has become, like much of American society, quite polarized, using a black-and-white lens to look at the culture that surrounds us with little opportunity to see the grey areas in which most of us live. You’re either in or you are out. And if you intermarry, many would say, “You are out.” This approach limits our options.

While historical Jewish tradition established boundaries, even dedicated an entire tractate of Talmud to the notion of boundaries, the dynamics of Jewish civilization reflected the nuances of life, especially as religious leaders confronted the reality of the evolving world around us. The rabbis in attendance openly and sensitively came to grapple with these nuances, though most were schooled in a culture of black and white with little room for grey when it comes to any issue related to intermarriage. Thus, much of what was presented to them was eye-opening and counterintuitive, information and observations based on many years of work with intermarried couples and their families by Big Tent Judaism. The emphasis was on people, not numbers. These families, like their in-married counterparts, are not monolithic. They, too, fall along a continuum of practice and identity.

What most captured the attention of the group were the various nuances in the religious lives of these intermarried families. For example, it was the first time that these rabbis were asked to consider that those who raised their children in what might be called “American civil religion” with a smattering of Chanukah and Christmas — and even Passover and Easter — were not raising their children in two faiths. These families probably reflected the majority of intermarried families and were a primary target population for outreach and connection. It was difficult for the rabbis to imagine people born into other faiths — perhaps still committed to those faiths — yet able to create Jewish homes and families and raise Jewish children, even sending them to Orthodox day schools and participating in Jewish community life. But they were open to this new understanding of the complexities of Jewish life.

The rabbis also struggled with issues of patrilineal descent and the idea that the children of intermarriage (when the father is Jewish and the other partner is not) could be considered Jewish, even if not Jewish according to halacha. This topic also emerged while debating the validity of conversions by non-Orthodox rabbis.

We also discussed the trends in Jewish demographics that show an increase in the number of Muslim-Jewish intermarriages, perhaps the most complicated of them all. Finally, participants were asked to consider the idea of second marriages and blended families in which children might be brought up in different faiths than their half or steps-siblings and how to work with these families who are a growing population segment among those who have intermarried.

This symposium showed that Orthodoxy could maintain its fidelity to halacha and tradition while being sensitive to the complexities and realities of the diverse Jewish community. In fact, the Orthodox community might be critical in enabling intermarriage to not be “the end of the line,” but, rather, a challenge leading to a deeper relationship to Judaism and the Jewish community.

Rabbi Kerry Olitzky is executive director of Big Tent Judaism. Rabbi Asher Lopatin is president of Yeshivat Chovevei Torah.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.