(New York Jewish Week) — Etgar Keret wrote his first story while serving in the IDF, during a long shift in a windowless room. It was soon after a friend killed himself, and Keret wasn’t sure why he wrote it or its purpose. But in those made-up sentences, he discovered magic.

Thirty year later, during an interview last week in New York City, Keret speaks with a hint of a smile, which sometimes turns into wide grin. He seems to weigh his words as he says them, with a quirky mindfulness, as though he is forming a story as he speaks.

Keret, 49, was in town to receive the 2016 Charles Bronfman Prize in “recognition of his work conveying Jewish values across cultures and imparting a humanitarian vision throughout the world.” Past recipients of the $100,000 prize include environmentalist Dr. Alon Tal and human rights activist Rachel Andres. The award-winning author of five collections of short stories, one memoir, four graphic novels, four children’s books and several screenplays, Keret is the first artist to receive the prize.

He says that winning a prize like this — “together with a list of people who have been doing amazing things in the world” — means much more than a literary prize. “Maybe writing does make people see things in a slightly different light. It’s the biggest compliment an artist can get.”

Keret is one of the leading voices in Israeli literature. At 49, he’s a generation younger than Amos Oz and A.B. Yehoshua, and more than a decade younger than David Grossman. He holds those writers in high esteem and says, “We live in a region where, almost by default, writers are kind of secular prophets.” He’s closest with Oz. In fact, he mailed that first story to Oz, in an envelope with just his name and his city, Arad. A few days later, Keret got a hand-written note, not praising the “poetic merit of the story but trying to comfort me.”

“We live in a region where, almost by default, writers are kind of secular prophets.”

Among the writers he’s closest to in his generation — even though he says he doesn’t really hang out with any writers — he names Sayed Kashua, a Palestinian-Israeli now living in the U.S., who was one of Keret’s nominators for the Bronfman Prize.

“It’s almost like our stories are friends, and we are the parents of our stories,” he says. I really love what he writes and really admire the kind of stand that he takes.”

About receiving an award for Jewish values, Keret says that “talking about Jewish values is like talking about love. Some people think that love is being selfless, others think it’s about having the stamina to have sex five times in a row. There are many things that I see as distinctly Jewish, not that I think that we have a patent on it.”

“For me being Jewish has to do a lot with the polemic,” he says. “In cheder you learn in chevruta [paired study]. You learn by arguing about the text. A lot of Christianity is about submission; I think Judaism is about finding your own way, not taking anything for granted, debating about things.”

“Another thing is reflectiveness. In the last election, Naftali Bennett of Jewish Home ran on the slogan, ‘From now on we stop apologizing’ — in reaction to all those left-wing people like me. My first reaction was: So, what are you going to do, cancel the Day of Atonement? What kind of Jew cannot reflect on what he did wrong and say sorry for that? For me, Yom Kippur is the most important and most unique holiday, for all the reasons that I know.”

“For me being Jewish has to do a lot with the polemic… I think Judaism is about finding your own way, not taking anything for granted, debating about things.”

“I’m an agnostic. In school, they ask my son if he comes from a religious home. He says, ‘My aunt says there is a god, my mother says no, me and my dad haven’t decided.’ It’s not that I haven’t decided. I believe there is something transcendental. I’m not a materialist.” But then he wonders how people can know if a moment is transcendental. “Does it come with manual, like a washing machine?”

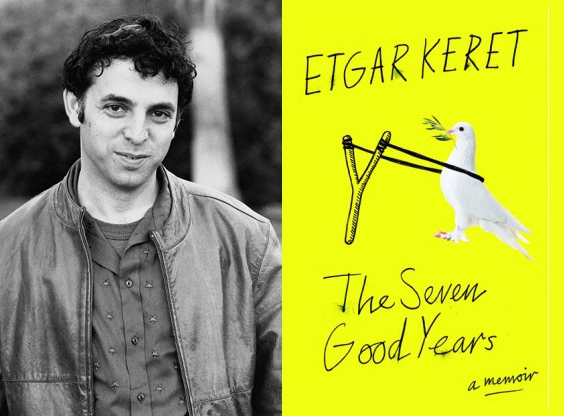

Keret’s latest book, “The Seven Good Years” (Riverhead) is a memoir in short pieces with wide emotional range. He focuses on the period between the birth of his son Lev and the death of his beloved father from cancer. The settings are Tel Aviv streets, his parents’ home, his son’s preschool, and one night alone in the Zagreb Museum of Contemporary Art, in advance of the local literary festival. His writing is spare, with telling details, stories within stories, unexpected twists. The reader comes to understand something about life in Israel, the anxieties of war, the complex legacy of being a son of Holocaust survivors — his father hid in a small hole in the ground in a Polish town for almost 600 days. He writes with an open heart, and manages to be light and funny and deep, at once. To read an Etgar Keret story is to become Keret for a few pages, or at least to walk beside him.

His wife Shira, a writer and filmmaker, appears throughout, and so do many taxi drivers, noted for their terrible driving and unsolicited advice — and then there’s the driver Keret invites home to use the bathroom, to his wife’s rebuke.

He says that his father once said, “In half of your stories the father character dies and in the other half he is just plain stupid, but in all of them I feel that you love me.”

Keret writes about the shiva, when he and his siblings gather at their parents’ home and listen to stories — some unknown to them — visitors tell about their late father. As shiva concludes, the three siblings linger together before they go off to sleep in their childhood rooms, and then off to separate lives, one sister in a Breslov chasidic community, the brother in Thailand (he’s now back in Israel).

In the interview, he says that when his sister became ultra-Orthodox more than 30 years ago, it was difficult for them to find topics for conversation.

“She didn’t go see movies. I wasn’t good at Bible. Talking about mitzvah, I wasn’t the perfect partner for that,” he says. So they started reading stories of Rabbi Nachman of Breslov together. “I could talk about storytelling, and she could talk about what’s behind the stories.” He says that reading those stories had an effect on his writing, and even wrote some stories that he describes as the kid brothers of chasidic tales.

Keret also writes newspaper Op-Eds, voicing opposition to the occupation and to harsh treatment of the Palestinians. At the Bronfman award ceremony, in conversation with public radio personality Ira Glass, he said, that unlike writing fiction, which is “like levitating in the air,” writing Op-Eds is like “doing the dishes or taking out the garbage. It’s a chore.”

Now he’s finishing up a new book and working with his wife on a television show “about real estate and time travel, but in a good way,” and they hope to shoot it for French television next year.

“We all know how we get into this world and how we are going to go out, and if you can do something in the middle, something meaningful that will affect the lives of others, then you are really, really lucky. I’m not talking about the work but about yourself — then you are really, really lucky.”

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.