(New York Jewish Week via JTA) — For most New Yorkers, the early days of COVID-19 were synonymous with eerily empty streets, the constant wail of sirens, and the clapping and cheering for health care workers. But what was it really like for the doctors and other health care professionals who found themselves on the front lines of a city that was an epicenter for the global pandemic?

More than most city residents, Emma Goldberg, a young journalist building her career at The New York Times, saw what was happening to the people in those hospital wards — especially the young physicians who graduated a few months early from medical school in order to support the massive influx of coronavirus patients at New York City’s Bellevue and Montefiore Medical Center.

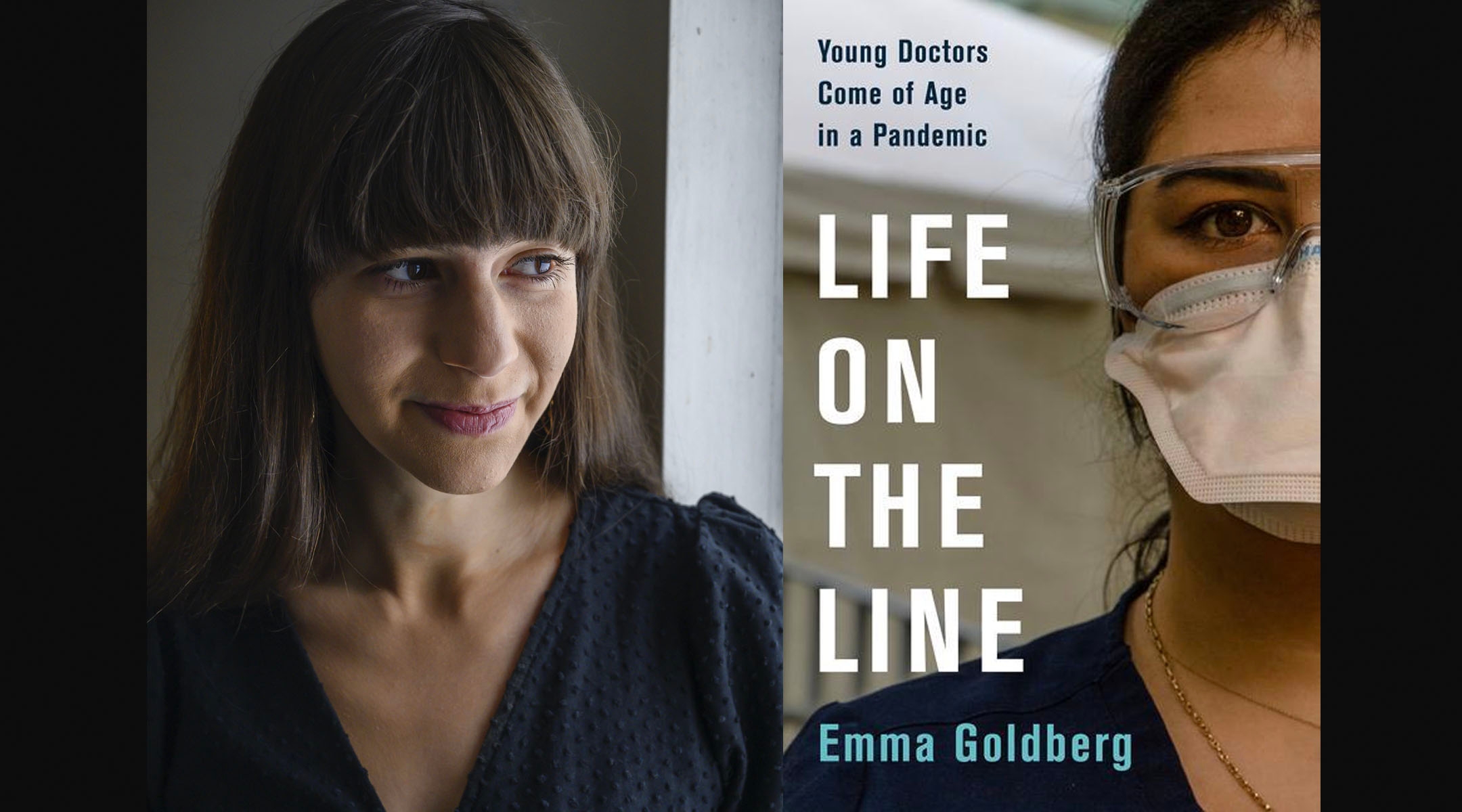

Her book, “Life on the Line: Young Doctors Come of Age in a Pandemic” (Harper), offers an in-depth look at how six newly minted young doctors — Sam, Gabriela, Iris, Elana, Jay and Ben — began their medical careers in the very heart of a global, and frighteningly local, pandemic.

“I had never lived through a moment that hit New York that hard, where it felt like we were really living almost in a crisis zone of sorts, and it was really eerie, just seeing the streets completely empty out,” Goldberg, 27, told The Jewish Week. “And so for me there was a real glimmer of hope in getting to talk with people who were around my own age, in their mid- to late 20s, who were doing something incredibly constructive, incredibly valuable, in stepping up to the front lines to be of service to the city in this moment of need.”

Goldberg, an editorial assistant at The Times with responsibilities that include research and fact-checking, was already reporting about issues of gender and health and the many inequities in medical education. In November 2019, she recalled, “I reported a story about all of the invisible costs of medical education, and beyond the cost of tuition, all of the other sort of stumbling blocks for lower-income people who want to enter medicine.”

Those include the cost of flying to interviews for medical schools, exam fees and expensive study guides.

And then, on March 1, 2020, Gov. Andrew Cuomo announced the state’s first confirmed COVID-19 case — a health care worker believed to have contracted the infection while traveling in Iran.

By March 26 of that year, the state had recorded 8,500 cases, 4,600 hospitalizations and 49 deaths. Goldberg reported a story that day about U.S. medical schools that decided to graduate their fourth-year students early and send them, if they chose, to support the overwhelmed doctors treating coronavirus patients.

“It was this moment of so much paralysis and anxiety, I think particularly for journalists, because we’re so used to being out there in the thick of the action, and instead we were all trapped in our apartments, just looking at headlines at how New York was a sort of war zone,” she said. “So I found it an incredibly inspiring story, and I knew it was one that I wanted to continue following.”

Goldberg worked with the medical schools to identify young doctors who were willing to share their experiences.

“They made the time because they were incredibly generous. They were working 10 hours a day in the hospital, and then they would call me … it was often late at night,” she recalled. Other times they “would call me from the grocery store, or on their way home, and sometimes they would speak going on their lunch breaks and call me.”

A book contract followed, and she reported “Life on the Line” mostly from April to December 2020. The book describes brand-new doctors who “couldn’t spend any more time with their patients than was clinically necessary,” and “spent much of their time helping their patients determine how they wanted to die.”

“And the grief felt all the sharper for those in the newest cohort of doctors who didn’t look like their predecessors — working-class people and people of color who’d gone into medicine only to see Covid-19 ravaging the very communities they’d set out to serve,” she wrote in an essay adapted from the book.

Goldberg, who grew up on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, has had no personal shortage of role models encouraging her journalistic pursuits, including her father, J.J. Goldberg, editor emeritus of the Forward. Her mother, Shifra Bronznick, served as founding president of Advancing Women Professionals and the Jewish Community, which is helping women break the glass ceiling in Jewish leadership roles.

“I always grew up just kind of revering books, like we had this home that was filled with books, and so it made me kind of from a really young age dream about wanting to write,” Goldberg said. The family was and continues to be involved with Minyan M’at, a lay-led traditional egalitarian minyan at New York’s Ansche Chesed.

She attended the pluralistic Abraham Joshua Heschel School, where she was involved with its student newspaper, writing about “questions of feminism in the Orthodox minyan and questions of kashrut at the school and meat-packing plants. I was kind of pursuing those Jewish stories and Jewish journalism was what kind of sparked my interest in going into the field.”

Along the way she received mentoring from Samuel Freedman, a journalism professor at Columbia University who volunteered as an adviser for Heschel’s student newspaper, the Helios. In an email to The Jewish Week, he wrote, “Emma has been a tireless reporter, a courageous thinker, a lucid writer, and, considering those talents, a strikingly modest person ever since I began working with her.”

After high school, Goldberg went on to receive her bachelor’s degree from Yale University and her MPhil in gender studies at Cambridge University. At an age when other reporters are happy to be collecting bylines, she was named best new journalist by the Newswomen’s Club of New York and received the Sidney Hillman Foundation’s Sidney Award for co-writing a story about the abuse of clients at the city’s Human Resources Agency.

Two of the six subjects in her book are Jewish, and one of her favorite parts about reporting the book was connecting with them, hearing “where questions of faith were particularly challenging for them during the course of the pandemic.”

One of the interns, Elana, is an Orthodox Jew who struggled with the question of working in the hospital on Shabbat. Another intern, Sam, a member of New York’s Congregation Beit Simchat Torah, “was exploring how Jewish summer camp affected his views on sexuality and sexual health. So I felt like there was just this incredible bond because I had the language and the kind of shared experiences to connect with them over the ways in which their Jewish identity informs their work.”

As a journalist at The Times since May 2019, Goldberg is aware of the outsize role the newspaper plays in the minds of the city’s Jews, from those who find it indispensable to others who insist it is biased in its coverage of Israel.

“I’ll just say in general that their coverage is incredibly rigorous, balanced, fair and strong, and I’m proud at all times to work for the organization,” she said.

Goldberg, who lives in Brooklyn’s Park Slope, is gratified by the city’s gradual return to life since the pandemic’s darkest days. She’s had the delayed opportunity of having dinner in person with the doctors in the book.

“I’ve never felt so kind of connected to the city,” Goldberg said, “and I did feel like New York City kind of felt like a character that was springing to life in the book, too.”

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.