(New York Jewish Week) – On a recent afternoon at the headquarters of Operation H.O.O.D. in Coney Island, just hours before three to four dozen teenagers are due to roll through the building for an afternoon full of activities, the four staff members discuss what they have planned.

They make sure the dumbbells and exercise machines in the weight room are organized and working, the Xboxes are turned on, the pool table is racked and the art supplies are out.

Derick Latif Scott, the program director, is busy scheduling the programming events through the rest of the year, which include basketball tournaments, Secret Santa giveaways and pop-up cookouts. He is also fielding calls from the 60th Police Precinct and a State Assembly member who are asking for information about a shooting that happened near the Coney Island Boardwalk the night before.

Operation H.O.O.D., which stands for Helping Our Own Develop, is part of the city’s Cure Violence initiative — a method of treating gun violence as a public health issue. Piloted by Jewish epidemiologist Gary Slutkin in Chicago in the early 2000s, the approach treats street violence as a disease needing to be interrupted and prevented.

At their new 3,000-square-foot headquarters and walk-in center on Mermaid Avenue in Coney Island, local kids and teenagers can come after school and on the weekends to keep busy and stay safe.

“They really believe it is a safe haven in the neighborhood,” staff member Howard Ayers, who is known as “Papa Bear” by the kids, told the New York Jewish Week.

Operation H.O.O.D. is also one of the social services operated in the neighborhood through the Jewish Community Council of Greater Coney Island, whose own headquarters are just a few blocks away from the Operation H.O.O.D. site. The Jewish non-profit helps operate the organization’s $1.8 million budget and secure more funding from the city and state, and assists in acquiring additional social services within the program, like mental health counseling and conflict resolution programs in nearby public schools.

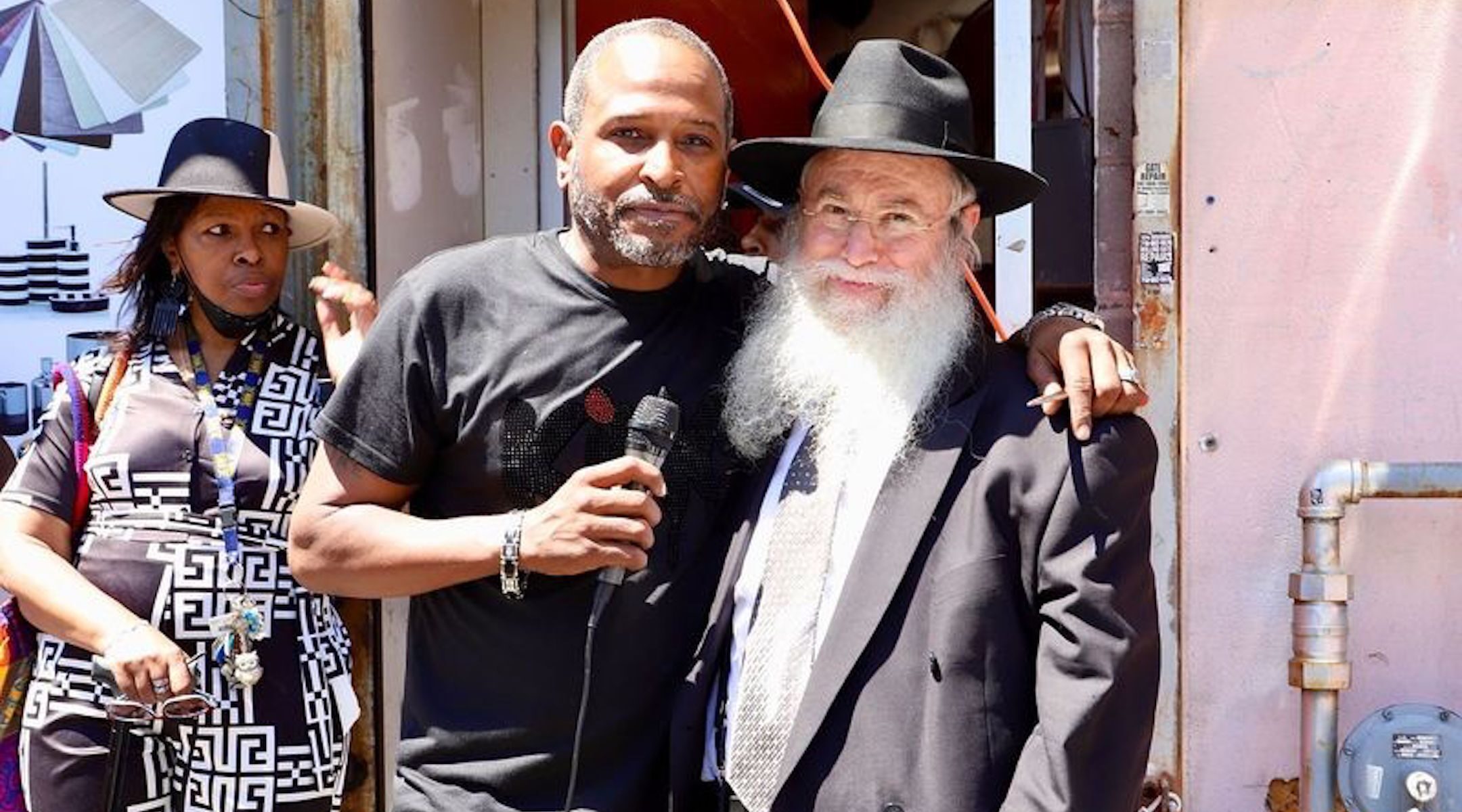

Rabbi Moshe Wiener has been the executive director of the Jewish Community Council of Greater Coney Island since 1981. “In keeping with the biblically mandated role of the Jewish people as ‘a light unto the nations,’ the duty of a Jew in carrying out his mission in life includes not only service to the Jewish people, but also service to the society and world at large,” Wiener told the New York Jewish Week about his nonprofit’s role with Operation H.O.O.D.

The previous night’s shooting is the reason the headquarters is understaffed that afternoon: The rest of Operation H.O.O.D.’s team was out in the field doing “shooting response,” another facet of their anti-violence work.

Ayers runs most operations and activities at the recreation center, including boxing and weightlifting programs. “We really appreciate how much we’ve been able to give them with this space,” he says, reflecting on the new digs, which opened June 29.

Community members play pool at the new walk-in center and headquarters at Operation H.O.O.D. (Esti Lomnitz)

In addition to all the recreational activities, the space has a large office area and meeting room, where teens can meet with a social intake worker, complete homework or fill out job applications. A sign on the back wall reads, “If you can run a gang, you can run a company,” alongside other framed motivational quotes.

“It’s a drop in the bucket for what’s necessary,” Scott said. In another shooting the week before, five people were injured on the boardwalk. Coney Island has already had nearly 200 felonious assault complaints — attacks involving violent weapons — this year to date. That number is down 9% from the same period last year, according to data from the NYPD, and 56% since 1993.

The JCCGCI operates more than two dozen social, educational and vocational services citywide — like adult literacy programs, transportation shuttles, internship placement services, Holocaust Survivor case management and more — taking them on as one of the longest functioning social-welfare driven community organizations in the neighborhood, Wiener said. Founded in 1973 to foster neighborhood stabilization for low-income residents of Southern Brooklyn, JCCGCI now operates diverse programs in all five boroughs and many of its patrons are not Jewish.

“We believe that a caring Jewish social service system should assure that the local health, security and human service needs of both the Jewish and broader community are addressed effectively and efficiently and bring together the diverse populations and institutions of the community,” Wiener added.

Rabbi Moshe Wiener next to Operation H.O.O.D.’s games truck, equipped with toys and video games. Staff members drive the truck around the neighborhood on the weekends, attracting 70 or 80 kids a day. (Julia Gergely)

The JCCGCI receives federal, state and local funding for its programs, as well as funding from both non-Jewish and Jewish philanthropies, including UJA-Federation. (UJA-Federation is a funder of 70 Faces Media, the New York Jewish Week’s parent company.) ) It is often sought out for its expertise on social services and community initiatives, Wiener said.

This is why, in 2015, when then City Council member Mark Treyger was able to secure $250,000 for a new community anti-violence initiative that would help address crime in Coney Island and fulfill other unmet needs in the community, he trusted Wiener to manage it.

Wiener, in turn, enlisted Scott, whom he knew as “one of the pioneers in bringing Cure Violence to New York,” through several community initiatives, including an organization called Save Our Streets.

Operation H.O.O.D. was officially founded in early 2016. By October, Coney Island was celebrating more than six months without a shooting, a feat that has now been accomplished several times over. Operation H.O.O.D. also operates as a Crisis Management System site for Coney Island as part of New York City’s Office to Prevent of Gun Violence. According to the city’s website, there was a 40% reduction in shootings from 2010-2019 due, in part, to the existence and funding of CMS sites like Operation H.O.O.D.

Now, with 27 team members and a budget that continues to grow, Scott still feels there aren’t enough people to do all the work that needs to be done in Coney Island and neighboring communities — even with members on call 24 hours a day.

Oftentimes, Scott said, the staff of Operation H.O.O.D. — who are trained in crisis management — are called to the scene of a shooting or a stabbing before the police (“nobody wants to deal with the police being there,” he said).

At scenes of shootings, where they are unarmed, or sometimes even at the hospital with the victim, they reason with both the assailant and the victims, talking them down from retribution — or from anger and from fear, which Scott said is what fuels much of the violence and crime in these communities, something he learned from experience growing up in Brownsville, Brooklyn.

“We’re trying to pull you up from the streets, at least to the sidewalk. Everybody is a work in progress,” Scott said. “We try to utilize fear as a conduit for something positive. Just focus on staying on the sidewalk.”

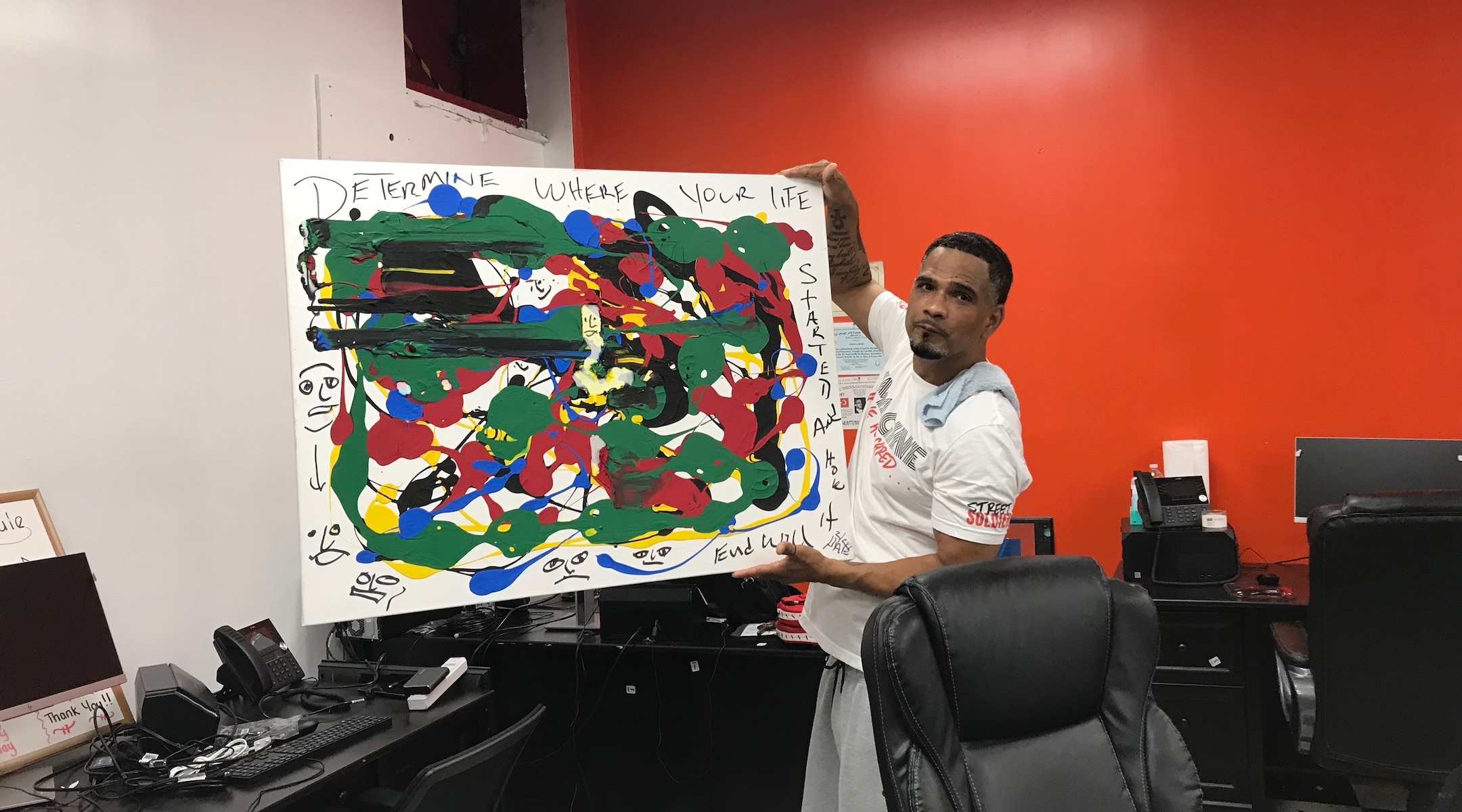

Staff member Nelson Villianueva holds artwork made by one of the students at Operation H.O.O.D. “Determine where your life started and how it will end,” the painting reads. (Julia Gergely)

The majority of the staff at Operation H.O.O.D. grew up in the neighborhood or in other nearby areas of Brooklyn, have been involved in the criminal justice system at some point in their lives and are now using that experience to motivate at-risk youth from taking the same path, making them “Credible Messengers.”

“We see ourselves as people that have been there, that have seen a lot. We don’t want these kids to go to the same places we have been,” Scott said.

“I’m on this Earth for a reason. I do it all for the kids.” said Operation H.O.O.D. staff member Samuel Zulueta, who runs kickboxing classes, coaches a football team, does personal training, and is one of the only members on staff who hasn’t been in prison. Zulueta is the youngest member on staff, having joined the team around two months ago, he said.

“The kids are everything,” he added. “They deserve to be kids.”

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.