Rifling through stacks of dusty cardboard boxes, Sarah Hopley opened one and found a faded manilla folder that looked promising. Its label read “KKK, 1983 JUN-1989.”

“Here we go. Klan from the ’80s,” she said. “We’ll find some sad stuff in here.”

Inside the folder were a variety of publications by and about the white supremacist group, from a flier advocating for “white Christian civilization” to newspaper clippings about KKK rallies to an advertisement for a forum hosted by the John Brown Anti-Klan Organizing Committee, a mostly-forgotten anti-racist group that would counterprotest KKK rallies.

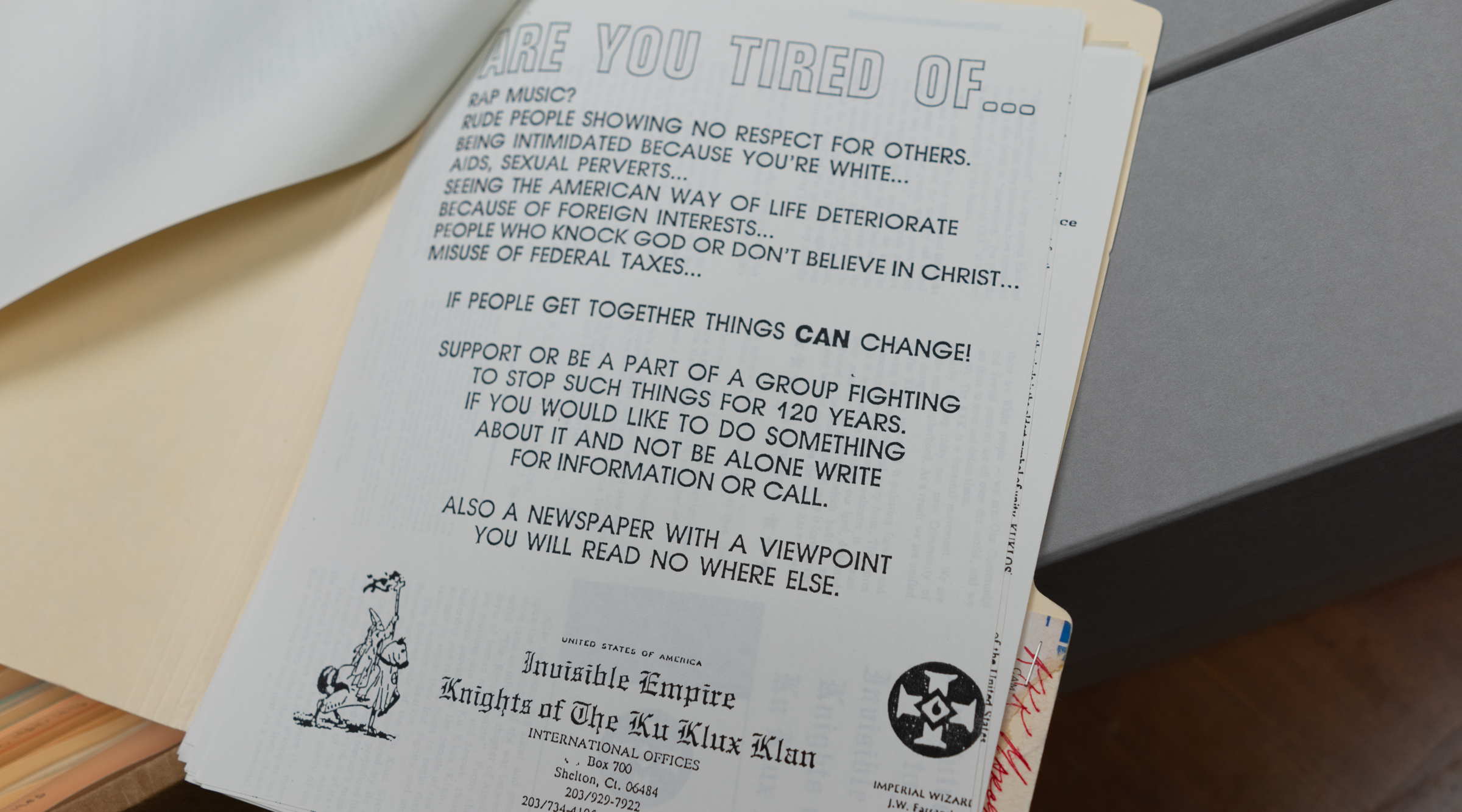

“Are you tired of… rap music?” begins one all-caps flier from the box, put out by a Klan group that called itself the “Invisible Empire.” “Support or be part of a group fighting to stop such things for 120 years.”

Since January, and for the next eight years, sifting through documents like this this will be Hopley’s full-time job: She and other archivists will go through thousands and thousands of boxes sent into New York City from a warehouse in New Jersey, working file by file to catalog, preserve and digitize decades of archives from the offices of the Anti-Defamation League.

Some of the boxes have not been opened for decades. Once the project is complete, the archive will be housed at the American Jewish Historical Society, part of the Center for Jewish History near Union Square in Manhattan, where it will be open to researchers and the public.

As the archive takes shape, Hopley and her colleagues hope the project will shed light on the history of hate groups, in a boon for researchers that could help combat discrimination in America today. She also hopes that seeing the same hateful ideas crop up in different forms throughout the decades will help dispel some of their salience — for example, decades of warnings that illegal aliens are set to overrun the United States and drive out white people.

“We can just say, ‘You’ve been saying this for 70 years and it’s never happened,’ and we can prove that,” she said.

“I don’t think there’s anyone that truly understands the wealth of information that’s held in these boxes,” Hopley added. “Once we get [through] this process, there will be no collection like it.”

Pictures of Ku Klux Klan members in from ADL archives. (Luke Tress)

The files contain a wide array of information, illustrating the breadth of the work of the ADL, which began in 1913 and has grown today into a global organization with a budget of $100 million. The files come from regional offices across the country, and span the ADL’s work in research, community involvement, undercover operations and monitoring of events across the decades.

During a recent visit to AJHS office by the New York Jewish Week, most of the files pulled from the warehouse focused on civil rights efforts, monitoring white supremacist groups and tracking political figures. One of the boxes, from a regional office in Denver, held folders labeled “Ku Klux Klan 1941-42,” “Civil Rts Comm,” and “Johnson, Edwin C.,” a Colorado senator and governor who died in 1970. The boxes are largely organized by topic, not chronology.

“We have been sitting on this collection. We have not been mining it for all the richness that it has in an effective way, and this is going to give us the opportunity to really do that,” Steven Freeman, the director of legacy at the ADL, said. In the absence of any comprehensive histories of the organization, Freeman also hopes the project will tell the story of the ADL.

The files included newspaper clippings, handwritten reports from ADL operatives in the field and material published by hate groups. An undated issue of the “Texas Klansman” showed masked men parading down a street in Houston. Another folder titled “KKK photographs” had polaroids showing a woman in Klan attire in front of a Confederate flag, and another woman in military fatigues showing off an M16 rifle.

The ADL sometimes monitored groups for years to determine if they posed a threat, Hopley said. A sheet of looseleaf chronicled a southern white supremacist meeting in the 1960s, with the writer reporting that attendees had discussed “the old crap of the ‘New York Jews.’”

“If there is any violent ones who now attend I did not see them. All of the Bad KKK are now underground,” the handwritten report said.

The archives comprise an estimated 13,000 to 14,000 boxes dating to the ADL’s founding. The material is roughly five times larger than AJHS’ current largest collection. Researchers do not have an estimate of how many files are in the boxes. In addition to papers, the boxes hold audio files, videos and around 6 million pages of microfilm. The ADL Archives Project will go through materials spanning from 1913 until 2000.

The documents show how hate groups have employed the same ideas over the past 100 years, even as the technology for disseminating the material has changed. A document from the 1960s showed a directory for Let Freedom Ring, a phone service that played pre-recorded antisemitic messages to members of the public who called in. A 1985 printout provided information on “The Klan Advocate Network,” an early online system for white supremacists that was active for eight hours each day. The sheet described how e-mail and a “public bulletin board” worked.

“Read current news and views that you won’t see on the jew controlled tv, or in the jew controlled newspaper,” the sheet said.

Much of the rhetoric is starkly similar to today’s. Documents from the 1960s described an incident in which a Black person who was eating pizza in his car was pulled out and beaten by police, along with efforts to combat stop-and-frisk laws. White supremacist material from decades ago warned against immigration and called for “America first” policies and military force on the southern border. A 1980 cartoon from the Texas Palestine Committee showed a pig branded with a Star of David and text referencing “greedy Jews.”

“Part of our original mandate, which is still true today, was to stop the defamation of the Jewish people and to secure justice and fair treatment for all,” Freeman said. “The main thrust of our work has been fighting antisemitism but there has been a realization that in order to fight antisemitism you have to find allies who are going to support you and you have to be willing to speak out.”

A file on Sen. Joe McCarthy in the ADL archives. (Luke Tress)

As they do today, members of the public would contact the ADL with tips that the organization would investigate, yielding anecdotes about what Jews experienced as threatening through the ages.

“They have just pages and pages of letters of people being, like, ‘My neighbor speaks German. I think she likes Hitler,’ and other ones, like, ‘They have a swastika in their house that I saw,’” Hopley said.

When discrimination at hotels was common, a Jewish person might tell the ADL they were denied a room. The ADL would then try to book a room at the same establishment under a non-Jewish name to determine whether the incident was discriminatory. The ADL used to put out bulletins with the results of its investigations, similar to reports posted online by the organization’s Center on Extremism today.

The files also contain the ADL’s responses to complaints of discrimination. If the organization found evidence of discrimination, it would often approach the offender politely to ask them to stop or apologize. If that didn’t work, the group would take legal action or make a public statement such as an op-ed in a newspaper.

The files had been housed at the ADL’s regional offices around the country until the 1980s, when the ADL hired Col. Seymour Pomrenze, one of the “Monuments Men” who tracked down Nazi-looted art in World War II, to start a records management program. Pomrenze had the regional offices ship the files to the New Jersey warehouse, where they were stored and preserved. Most remain in good condition.

The ADL and the American Jewish Historical Society began the archives project in January. At the AJHS office, the archivists go through the material, identify major themes and names, and photograph the pages using a mounted Canon DSLR camera. The photographs are imported to a computer system, labeled with keywords, and uploaded into a digital asset management program. The physical documents will then be placed in acid-free containers that will better preserve them.

An advertisement for the Ku Klux Klan from the ADL archives. (Luke Tress)

The digitized files will be made available to researchers and the public in the coming years, probably starting in 2027. Some files that deal with confidential information, such as financial statements and the names of undercover operatives who may still be alive, will not be released.

Organizers also plan to assemble some of the files into a traveling exhibition that will be displayed at ADL offices around the country, and hope to produce a documentary film series about the archiving project, said Gemma Birnbaum, the executive director of AJHS.

The project will cost an estimated $6.5 million, not including the exhibition and film, Birnbaum said.

Hopley has been interested in hate groups since her youth in Illinois, where such groups were prevalent, she said. Her undergraduate senior thesis was on the Hitler Youth. She has worked for years as an archivist, was hired specifically for the ADL Archives Project and will be processing the files full-time for the duration of the initiative.

She called the project a “once in a lifetime opportunity for an archivist” that she took on even though poring over hateful material was personally taxing.

“You see people drawn as apes, or just terrible things about Jewish people,” she said. “You’re like, ‘I can’t believe these people exist in this world.’”

That material has changed over the years. Material from the 1940s focuses on Nazi sympathizers, which ADL staff repeatedly referred to as “rabble rousers.” In the 1950s, many of the reports were about persecution of alleged communists, and in the 1960s, the civil rights movement. Israel and anti-Zionism began to make a regular appearance in the 1960s and 1970s.

A 1963 folder with a schedule for an ADL National Civil Rights Committee meeting discussed how to respond to George Rockwell’s American Nazi Party.

“Should ADL argue that the use by Rockwell and the American Nazi Party of the swastika banner and Nazi Storm Troop type uniform in connection with their public demonstrations is a violation of the law, a form of disorderly conduct and ‘fighting words’ outside the First Amendment’s protection of freedom of speech?” the document asked.

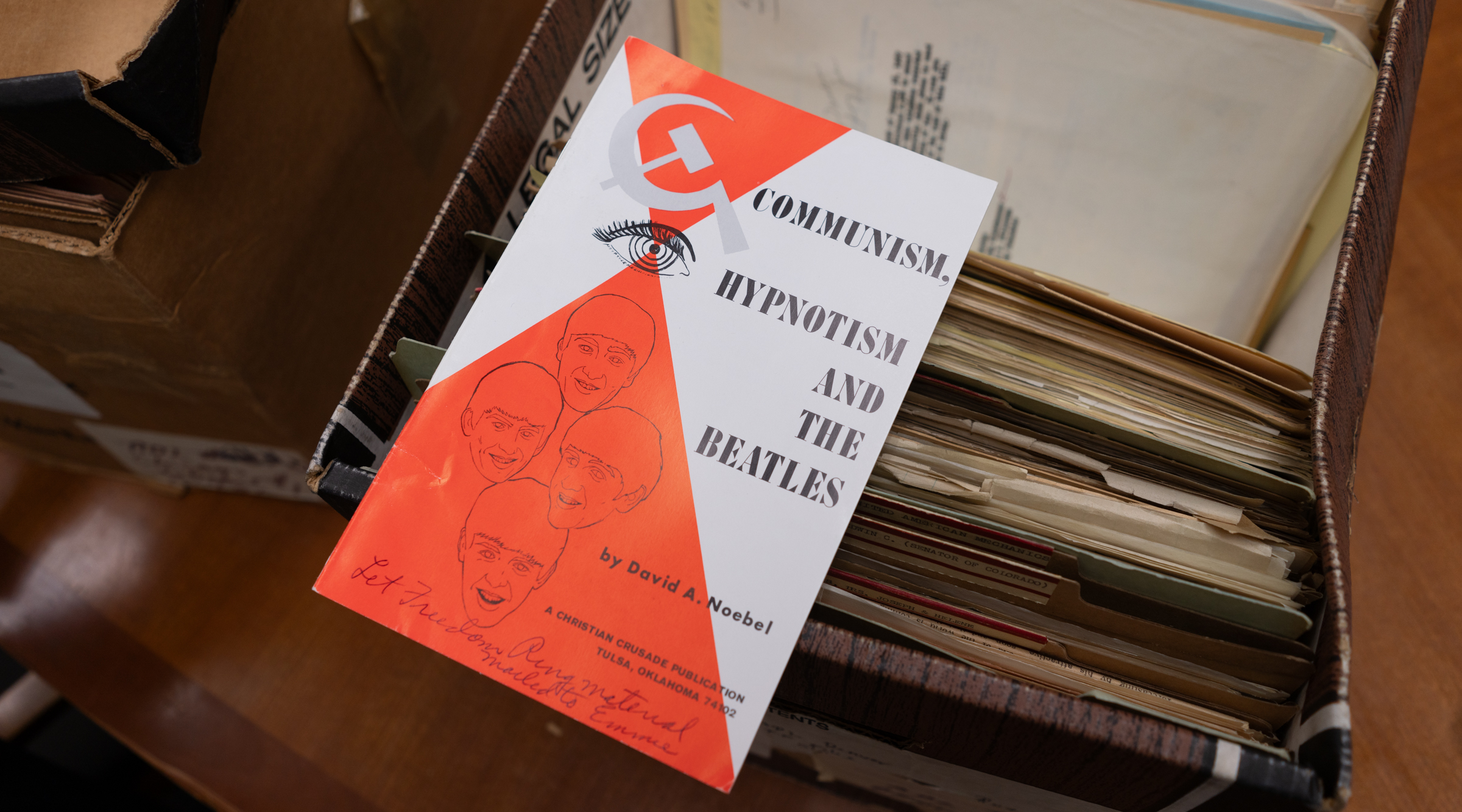

A booklet warning against the communist influence of the Beatles from the ADL archives. (Luke Tress)

Some of the material is confusing to the archivists, since much of the context was left out by experts who were familiar enough with the issues that explanations were omitted. One booklet, from a “Christian Crusade Publication” based in Tulsa, Oklahoma, was titled “Communism, Hypnotism and the Beatles,” with an image of a hammer and sickle above caricatures of the British quartet.

Archivists hope researchers will be able to answer those questions once the archives are organized.

“A lot of it does not make a lot of sense,” Hopley said. “It’s like, ‘What is this? Where did it come from? Why does it exist?’”

Even though the files show how hateful ideas have persisted despite a century of the ADL’s efforts, Hopley says the incremental, fastidious work of the archive has given her hope.

“I think you just keep hoping and working towards that change, because if we give up, then nothing’s going to get better, so you have to keep trying,” she said. “Looking at this and making this accessible will help that change, however slow that change may be.”

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.