The plots they hatched to spirit Jews out of Nazi-occupied Europe were simple, yet brilliant. Improvised as they were on the spur-of-the-perilous moment, and with lives on the line, they were morally audacious actions that still echo, however faintly, more than seven decades after they were taken.

In neutral Switzerland during World War II, a Catholic El Salvadoran soldier-turned-diplomat enlists a Jewish businessman from Transylvania and gives him a fictitious position pumping out bogus visas to protect threatened Jews.

In west-central Germany, the Lutheran scion of a world-famous camera manufacturing firm sets up a phony photography training course to rescue Jews from the Final Solution by preparing them for jobs overseas.

In Nazi-occupied Vienna, the Chinese consul general, moved by the principles of Confucianism and against the wishes of his government and the Gestapo, issues thousands of visas that allow Jews to travel to Shanghai, whose lawless port offered safe harbor.

And in occupied Paris, an Iranian Muslim diplomat-lawyer employs a questionable but savvy “ethnographic” argument to convince his superiors that Iranian Jews living in Paris weren’t really Jewish; it saved them.

None of these heroes of the Holocaust were Jewish. Few of their names, like that of the German industrialist Oskar Schindler, who saved 1,200 Jews and was the subject of a blockbuster Steven Spielberg film, are widely known today. Together, their clever and daring schemes helped save thousands of Jews from the Shoah.

On the eve of Yom HaShoah, Holocaust Remembrance Day (April 12), as the number of people with direct memory of the Holocaust dwindles, and the historical responsibility to salute wartime heroism takes on greater urgency, the issue has a contemporary political resonance. As part of the ongoing controversy over the new Polish law that bans any mention of Polish (or Poles’) responsibility for crimes committed against Jews during World War II, the government declared March 24 National Remembrance Day for Poles Who Saved Jews, shifting the focus of public attention from Polish culpability to the bravery of individual Polish citizens.

In other words, Poles like Irena Sendler, the nurse and social worker who as a member of the Polish underground smuggled more than 2,500 Jewish children out of the Warsaw Ghetto, are, depending on one’s point of view, either being used as political pawns while the nationalist far right gains steam in Poland and other parts of Europe, or receiving their long-overdue recognition.

“This day is meant to connect Poles with different views, but with a common belief that people who saved the Jewish population deserve respect,” said Wojciech Kolarski, undersecretary of state.

In the same vein, a letter signed last month by a group of 50 Poles honored as Righteous Gentiles by Yad Vashem, Israel’s national Holocaust memorial and museum, appealed to the governments of Poland and Israel (which had been highly critical of the new Polish legislation) to return “to the path of dialogue and reconciliation.”

Even as the tension between Poland and Israel lingers, the “other Schindlers” remain a moral force.

Yad Vashem has honored more than 26,000 people as “Righteous Among the Nations.” Given their heroics, some are compared to Schindler as a way to honor their deeds. Like Nicholas Winton, the “British Schindler,” who set up his own Kindertransport from Nazi-occupied Austria. (Winton technically was a Jew, raised in a family that had converted to Christianity, and he did not consider himself Jewish.) Or Chiune Sugihara, the “Japanese Schindler,” a diplomat who defied his government in issuing life-saving visas in Lithuania.

Some of these people saved a single Jew; others, an entire family; and a few others, hundreds of people. Or, like Schindler himself, thousands.

“The number of Jews rescued is not a part of the consideration of the commission which awards the [Righteous Gentile] title,” said Irena Steinfeldt, director of the Righteous Among the Nations Department at Yad Vashem.

“You don’t measure heroism by how many people they saved,” said Abraham Foxman, a Holocaust survivor who served as the longtime national director of the Anti-Defamation League and who himself was saved by a Polish Catholic nurse.

Most people in lands occupied by or allied with Nazi Germany “did nothing or were collaborators,” said Foxman, who called the acts of the Righteous Gentiles “a message to the world that people could make a difference.”

Most heroes of the Shoah are not better known, Foxman said, because survivors were reticent to discuss, or document, their experiences for several decades after World War II, and because it took someone with a story as dramatic as Schindler’s to personalize the exploits of the rescuers.

Mordecai Paldiel, former director of Yad Vashem’s Righteous Among the Nations Department, estimates that “probably over 100,000” non-Jews risked their lives to save some 250,000 Jews during the Holocaust.

A disproportionate number of these heroic individuals were diplomats. They “had the capacity to save more than some individual lonely persons who could save only one, two, a handful,” Paldiel said. “Diplomats could save hundreds and in some cases a few thousands by the simple act of issuing visas or other protective documents.”

While hundreds of Jews wrote diaries during the Holocaust, Foxman said, only Anne Frank’s has maintained a place on the public consciousness. “Just as Anne Frank is the representative of children of that period, Schindler is the symbol of all those who had the courage to save Jews.”

Like Schindler, many of the men and women who rescued Jews from the Shoah were “not saints,” said Agnes Grunwald-Spier, a Holocaust survivor from Hungary who wrote “The Other Schindlers: Why Some People Chose to Save Jews in the Holocaust” (The History Press, 2010). Some were anti-Semites, some were cheats, some were disreputable in other aspects of their lives.

But they risked their lives to save Jewish lives. Why did they do it?

The reasons varied, said Grunwald-Spier, author of the recently published “Women’s Experiences in the Holocaust In Their Own Words” (Amberley Publishing). The people she interviewed cited friendship, religious motivation, a feeling of humanitarianism, or membership in resistance movements. All shared in common “empathy. At the critical time they did the right thing.”

She continued: “They were all remarkably modest. They all said, ‘I didn’t do anything special. Anyone would do it.’”

“If everyone had done so, there would not have been a Holocaust. Such decency comes with humility,” said Holocaust historian Michael Berenbaum.

“Some of these people were more decent than Schindler, more altruistic than Schindler,” Berenbaum said. Schindler himself, a womanizing rogue who profited at the start of the war from the slave labor of Jews at his enamelware factory in Krakow, developed a conscience during the war and, at the risk of his life and business, saved Jews by a combination of bravery and subterfuge.

His actions, and those of others like him, are documented by Yad Vashem and various survivors’ organizations, and are the subject of a growing number of museum exhibitions.

The other Schindlers are not forgotten. Some 350 Righteous Gentiles receive monthly stipends from the New York-based Jewish Foundation for the Righteous.

But “Schindler’s List” made Oskar Schindler the name that most people know. The industrialist, said Grunwald-Spier, “taught the world about the Holocaust more than anyone else had done.”

“What it takes to be known by the public,” said Berenbaum, “is a film.”

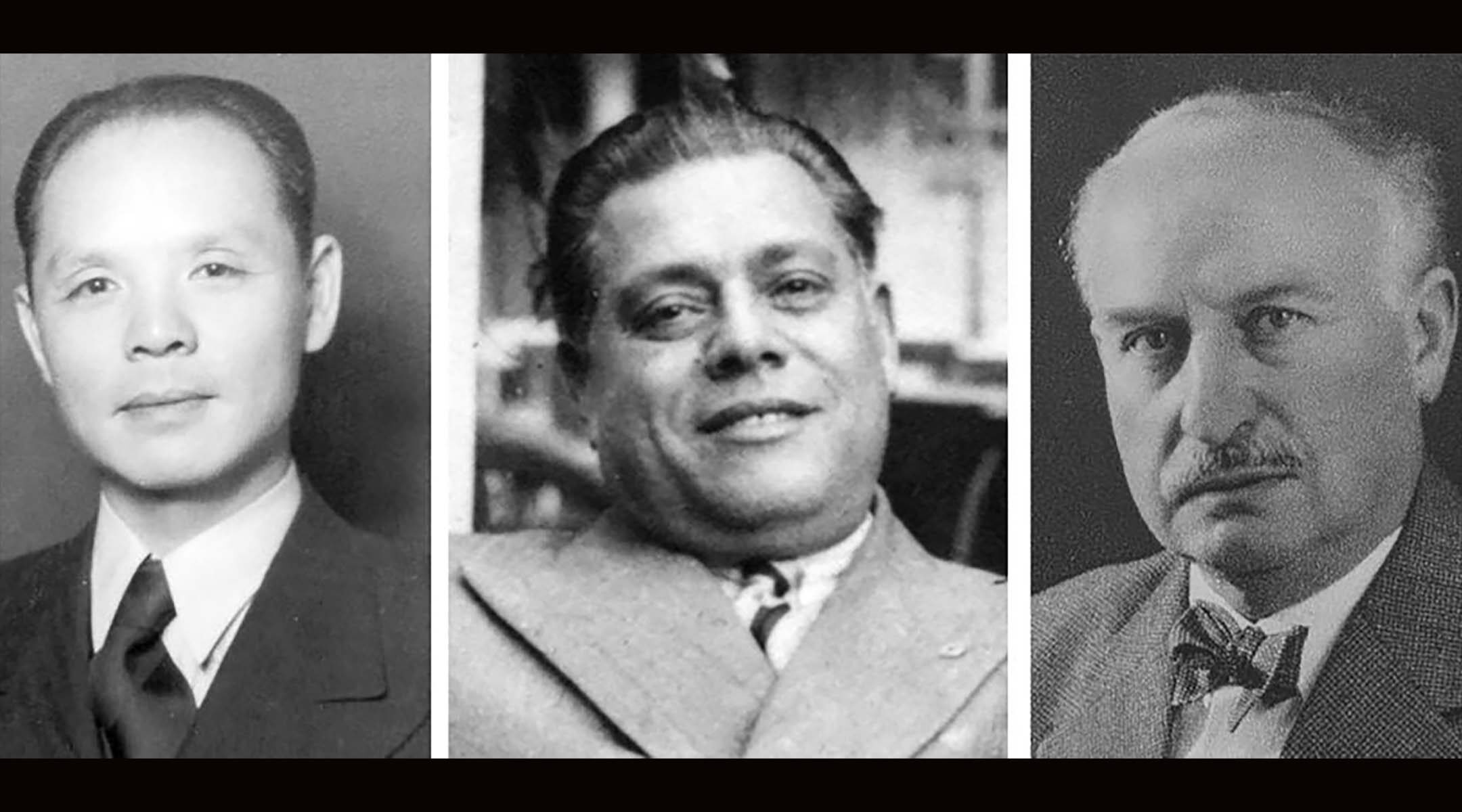

Jose Arturo Castellanos: Creating Secret Salvadoran Citizens

The government of Switzerland, where Castellanos was posted as a diplomat in 1942, was politically neutral, but Castellanos wasn’t.

El Salvador’s consul general to Geneva, he had learned of the danger that the Third Reich posed to the Jews of Europe during previous postings in London and Hamburg, and took matters into his own hands.

He enlisted Gyorgy Mandl, a Transylvanian-born Jewish businessman he had earlier met, and gave him and his family El Salvador visas. He appointed Mandl to the fictitious position of first secretary of the El Salvador Consulate, which afforded him diplomatic protection. Castellanos had Mandl change his last name to Mantello, which sounds more typically Salvadoran. And both men began producing and shipping Salvadoran visas and blank “certificates of Salvadoran citizenship” via courier to Jews in several European countries.

The documents were bogus; they carried no official status. But when presented to Nazi officials in Hungary, Romania, Poland, Czechoslovakia and Bulgaria, who respected bureaucracy, they were life-saving. The suddenly “Salvadoran” Jews became exempt from anti-Jewish edicts.

Ignoring orders from his superiors, who twice told him to cease his activities, Castellanos turned out an estimated 13,000 documents, protecting about 40,000 Jews.

“My father was very strong-willed,” his daughter, Frieda Castellanos de Garcia, who works as an interpreter in Washington, D.C., told The Jewish Week. “He did what was right.”

Castellanos would often tell his daughter, “Anyone in my position would have done the same.”

Was there a risk for Castellanos? “A lot,” Garcia said.

Castellanos and Mandl had to persuade suspicious Swiss and Hungarian officials that the documents were genuine, and that Central and Eastern Europe was home to a large Salvadoran diaspora.

A Catholic and an opponent of his homeland’s fascist government, Castellanos was a career soldier before being exiled to his diplomatic jobs in Europe. In 1944, a new government in El Salvador, more sympathetic to the plight of European Jewry, supported Castellanos’ work.

Castellanos, who retired in 1956 and died in 1977, never talked about what he did in Geneva. His activities came to light when a woman in the Swiss city discovered a suitcase in her basement that contained thousands of Castellanos’ citizenship certificates.

In 1999, a street in Jerusalem’s Givat Masua neighborhood was named El Salvador Street in Castellanos’ honor, and in 2012 the Anti-Defamation League posthumously gave him the Jan Karski Courage to Care Award, named for the heroic wartime Polish courier.

Ernst Leitz: A Lens on Heroism

The second-generation owner of the Leica camera business, which produced a precision instrument that revolutionized 33mm photography, Ernst Leitz II worked clandestinely on a rescue effort that helped bring some six-dozen endangered German Jews to safety in the U.S. and other Western countries.

Historians call Leitz’s humanitarian campaign the “Leica Freedom Train” — one that operated largely by boat.

A Lutheran, Leitz worked and lived in Wetzlar, a town in west-central Germany. “It was a small town — he knew everybody,” including the Jewish employees of his optics factory and other members of Wetzlar’s small Jewish community, Rabbi Frank Dabba Smith, Leitz’s biographer, told The Jewish Week.

After Adolf Hitler became Germany’s chancellor in 1933, and particularly after Kristallnacht in 1938, Leitz was approached by Jewish friends and strangers requesting help in leaving the country. As a non-Jew, exempt from the Nuremberg Laws, he and his family had greater freedom of movement.

In the guise of preparing Jewish employees to work abroad, Leitz began offering specialized training. He then “assigned” them to positions overseas, especially the Leica showroom in Manhattan, wrote letters of recommendation, paid for their boat tickets, arranged for jobs in the photography business, paid a stipend till they were settled in their new lives, and arranged for housing. And everyone got a free Leica camera.

“He couldn’t stand the suffering,” said Rabbi Smith, a California native who has lived in England 30 years. He said Leitz saved 80 Jewish lives this way.

The Leica Freedom Train stopped when the borders closed with the start of WWII in September, 1939.

“The Nazis knew a great deal about what he was doing,” Rabbi Smith, who learned about Leitz’s exploits in a line in a profile in a photography magazine several decades ago, said in a telephone interview. The Gestapo, which had agents spying on him, was “very angry.”

How did he get away with it?

As an industrialist bringing needed foreign currency into Germany, manufacturing cameras and view finders for the German Army, Leitz occupied a privileged position. “He had a certain amount of leeway,” the rabbi said.

“He walked a tightrope,” coerced into belatedly joining the Nazi Party and employing Ukrainian women as forced laborers, whom he and his daughter treated humanely. “There was always a struggle between the ideologue” — Leitz had a background in “liberal-left politics” — “and the pragmatist,” Rabbi Smith said.

Leitz, who died in 1956, was posthumously honored by the Anti-Defamation League.

Feng-Shan Ho: A Sense of Confucianist Duty

To allow a Jew to leave, Nazi officials required proof of an applicant’s end destination.A month after Nazi Germany’s Anschluss annexation of Austria in March 1938, Ho was appointed the Chinese government’s consul general in Vienna. Austrian Jews, fearing the worst, immediately turned up at Ho’s office, seeking visas to enter China.

Ho, who in his brief time in Vienna witnessed anti-Semitism and persecution of Jews, began issuing visas to the port city of Shanghai, whose harbor, since the Japanese occupation of 1937, was left unmanned, with no passport control or immigration procedures. Anyone could enter without documents.

With the cooperation of other sympathetic diplomats, some18,000 Jews found refuge in Shanghai, yet most eventually moved on to Palestine, the United States, England and other Western countries. Years later, few Jews whose lives were saved by the visa ruse in which Ho played a crucial role “even knew his name,” said Manli Ho, his daughter, who now lives in Maine.

There is no record of how many visas Ho issued until he was posted to a new assignment in 1940, but his daughter estimates the figure at 4,000. She said that Ho never talked about his life-saving efforts in Vienna, and that his 700-page memoir manuscript contains only “30 words about Jews.”

Alerted to her father’s exploits by an obituary after he died in 1997, Manli Ho has devoted two decades to researching his time in Vienna. He befriended many Jews there, she says, kept issuing visas after his government told him to stop and the Gestapo threatened him at gunpoint, sometimes hand-delivering visas to the apartments of Jews, and opening an office at his own expense after the Consulate building was confiscated by the Nazis.

“My father was fierce, a man of supreme self-confidence,” she told The Jewish Week. Raised in poverty in rural China, left fatherless at an early age, he felt a natural kinship with the underdog. Educated at a Lutheran school, “he was not a particularly religious guy,” but was heavily influenced by the Confucianist credo of duty.

“Seeing the Jews so doomed,” he would later recall, “it was only natural to feel deep compassion, and from a humanitarian standpoint, to be impelled to help them.”

Ho retired to San Francisco in 1973; China cancelled his modest pension. “He was considered a maverick in the bureaucracy” his daughter said, “and mavericks don’t do well.”

Abdol Hossein Sardari: A Muslim Saving Jews in Occupied Paris

Sardari, who grew up in a privileged family in Iran, was the Iranian consul general in Paris early in World War II, under the direction of Iran’s ambassador. In May 1940, the German Army attacked France, the Nazis occupied the capital a month later, and the ambassador headed south, to Vichy in the unoccupied zone.

At that point, Sardari became what was the top Iranian diplomat in Paris.

Three months after the German occupation, authorities required all Jews in France to register with the police, and Sardari intervened to protect them.

Sardari, a Muslim, was a lawyer by training, a bon vivant bachelor who hosted lavish parties for high-ranking Nazis. Leaning on his legal background, his appeals to Nazi and Vichy officials described the 100 or so Jews from Iran, Afghanistan and Uzbekistan living in France as “Jugutis” (Djougoutes in French), longtime followers of Moses who, forced to convert to Islam a century earlier, continued to practice Judaism in the privacy of their homes.

In other words, he argued, based on “an ethnographic and historical study,” those Jews, assimilated into French culture, were now of Arab stock, and therefore exempt from Nazi racially-based persecution.

The Juguti claim had questionable validity — “the usual Jewish tricks and attempts at camouflage,” Adolf Eichmann is said to have commented — but it sounded plausible enough to buy time. The Third Reich’s Racial Policy Department turned for an answer to various Nazi racial institutes.

Meanwhile, the Iranian Jews were spared, not forced to wear the yellow Star of David. Eventually, Iranian Jews in both occupied and non-occupied France were safe.

Sardari, who died in 1981, tried to protect Iranians irrespective of religion; he is credited with distributing several hundred Iranian passports without the permission of his superiors, saving 2,000-3,000 Jewish lives. He also protected non-Iranian Jews in Paris, reportedly issuing them Iranian passports too.

Eventually, Iran stripped Sardari of his diplomatic immunity and his salary after the country signed a treaty with the Allies in 1941; he remained in Paris. His exploits were chronicled in Mahdieh Zardiny’s 2017 documentary, “Sardari’s Enigma.”

About his choice to help save Jews, Sardari would explain, “I did this because it was my duty to do this,” said his biographer, Fariborz Mokhtari, author of “In the Lion’s Shadow: The Iranian Schindler and his homeland in the Second World War” (The History Press). A native of Iran who came to the U.S. in 1979 and serves on the staff of the National Defense University in Washington, Mokhtari became interested in Sardari’s life after seeing a footnote in a book in 2002. n

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.