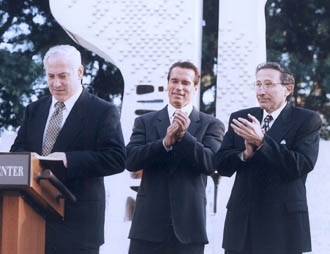

LOS ANGELES, Aug. 11 (JTA) — “The recall election is a circus and Arnold Schwarzenegger is expected to hold up the tent,” says Saul Turteltaub, a veteran television sitcom writer and producer. Turteltaub knows Schwarzenegger socially and thinks he is a nice guy and sincere person, but that doesn’t mean he’ll vote for the movie action hero for governor of California. “First, I’m a Democrat, and secondly, I think that the recall election is a bad idea,” Turteltaub says. Like the TV writer, most Los Angeles Jews to offer public comment on the issue seem tepid about both the election and Schwarzenegger’s bid as a Republican candidate. That’s partially because “Ahnold,” as he is universally addressed, hasn’t laid out any political agenda for tackling the state’s horrendous fiscal problems, and partially because the vast majority of California Jews are Democrats. The now-unpopular incumbent, Gov. Gray Davis, a Democrat, drew 69 percent of the Jewish vote in last November’s election. Sheldon Sloan, an attorney, former judge and founder of the Republican Jewish Coalition chapter in Los Angeles is one exception. “I’ve known Arnold for years,” Sloan says. “He is a moderate in politics, he knows how to pick good people and he is a very successful businessman — something people underestimate. In my Republican Jewish circle, most support Arnold.” Two aspects of Schwarzenegger’s past may give Jews pause. One is the fact that the father of the Austrian-born actor was a member of the Nazi Party and served in the German army during World War II. The second is the somewhat murky relationship of “The Terminator” with Kurt Waldheim, the former U.N. secretary-general. Rabbi Marvin Hier, founder and dean of the Simon Wiesenthal Center, recalls that in the mid-1980s, Schwarzenegger became an active member and patron of the center, and later its Museum of Tolerance. “In 1990, Arnold came to see me and said he was troubled because he really knew so little about his father,” Hier says. “He asked us to use our researchers and resources to track down his father’s past.” The search showed that Gustav Schwarzenegger, a small-town Austrian police official, tried to join the Nazi Party in 1938, immediately after the Anschluss, but was not formally inducted into the party until 1941. He served in the German army, stationed in Austria in a police function. No records or complaints were found to implicate the father in any war crimes or persecution of Jews. The actor’s relationship with Waldheim, who was barred from entering the United States because of his World War II record as a Nazi intelligence officer in the occupied Balkans, has been controversial. It seems clear that Schwarzenegger toasted the then-Austrian president, in absentia, when the actor married Maria Shriver in 1986, and he was later apparently photographed with Waldheim. But Hier puts this down more to political naivete than to ideological leanings. In any case, both Democratic and Republican political analysts agree that if no worse skeletons are found in Schwarzenegger’s closet, neither Jewish nor non-Jewish voters will be much troubled by this past. During his ongoing relationship with the Wiesenthal Center, Schwarzenegger has donated between $750,000 to $1 million of his own money, and he has raised millions more from others in parlor meetings, Hier says. Hier will not say how he will vote, but he says he feels a strong loyalty to Davis, the subject of the recall. Davis, he says, has been a strong supporter of his Wiesenthal Center, the Jewish community and Israel. Howard Welinsky, a veteran Democratic activist and chairman of Democrats for Israel, notes that the date of the recall election, Oct. 7, is the day after Yom Kippur. “I hope California Jews will have given some sober thoughts to the problems facing our state and vote against the recall,” he says. Hollywood, with its large Jewish contingent, might support Schwarzenegger as one of its own and in the hope that, as governor, he would take steps to halt the runaway production of movies from local studio lots to other states and countries. But don’t count on it, says Arnold Steinberg, a Republican consultant and pollster. “People in Hollywood usually separate their politics from their business,” he says. Steinberg believes that whatever Jewish votes go to Schwarzenegger will be mainly from younger Jews, who, he notes, have a tendency not to show up on polling days. Dr. Joel Strom, now chair of the local Republican Jewish Coalition, is supporting another Republican in the race, but he thinks that fewer Jewish Democrats will cross over to vote for Schwarzenegger than would have for former Los Angeles Mayor Richard Riordan, who is not in the running. According to polls, the one public figure who most easily could have turned back Schwarzenegger is the state’s Jewish U.S. senator, Dianne Feinstein. But she decided not to enter the race. A more-jaundiced view of the whole proceedings is taken by cultural critic Neal Gabler, author of “An Empire of Their Own: How the Jews Invented Hollywood.” Gabler sees in the recall election a validation of his thesis that politics in America has become a branch of he entertainment industry, in which life imitates art. “What California voters are doing is to consciously convert the political process into a movie,” Gabler says. “Arnold understands that the election has nothing to do with politics and everything with entertainment values.” The outcome of the election, the New York-based writer believes, hinges on what approach the media decides to take. “If the media reports this as a serious political issue, I don’t think Arnold will win,” Gabler says. “But if they treat this as just fun and games, then he’s in.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.